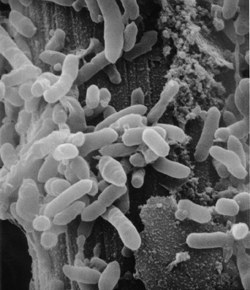

Gut bacteria that support healthy pregnancies cause disease in others

By Krishna Ramanujan

The microbial community found in the gut creates beneficial health conditions for pregnant women, a new study shows -- and strikingly, these same bacteria-driven conditions are considered unhealthy in non-pregnant people.

The study appearing Aug. 3 in the journal Cell shows that the gut bacteria in pregnant women undergo profound changes between the first and third trimesters. Furthermore, shifts in gut microbes drive changes that mimic metabolic syndrome -- with symptoms including insulin desensitization, weight gain and mild inflammation in the gut.

"In pregnant women, these changes are normal," said Ruth Ley, Cornell assistant professor of microbiology and senior author of the paper. The changes help pregnant women gain weight for increased energy and to meet the fetus' nutrient demands and to prepare for breastfeeding, she said.

"But outside of pregnancy, it's reminiscent of metabolic syndrome," which can lead to obesity and type 2 diabetes, she added.

Ley and colleagues examined the stools of 91 Finnish women during their first and third trimesters of pregnancy. The women all started with normal distributions of gut bacteria, but by the third trimester, their gut microbiota varied greatly and unpredictably. Also, healthy bacteria counts decreased while certain bacteria associated with inflammation increased in a majority of the women.

The women in the study varied in weight, and some suffered from gestational diabetes, but significant gut changes occurred regardless of their physical state, Ley said.

Furthermore, blood and diet data on the women showed that the changes were not diet related. Though causes behind the changes are unknown, they may be immune system or hormone related, Ley said.

The researchers also took special germ-free mice and inoculated them with gut microbiota from women in their first and third trimesters, respectively. The mice with gut bacteria from the later period gained more weight and developed reduced insulin sensitivity and greater gut inflammation. The experiment showed that microbiota from the third trimester can induce metabolic changes in mice that are similar to conditions in women in their third trimester and that gut bacteria drive the metabolic changes.

The findings suggest that the relationship between hosts and microbes, and the role of microbes in insulin sensitivity and weight gain may have origins in reproductive biology.

The researchers also had gut bacteria and health data from the children born to the women in the study sample. The children grew up normal regardless of the mother's health conditions. "There's no carryover to the babies that we can detect," Ley said.

Omry Koren, a postdoctoral researcher in Ley's lab, is the paper's lead author. The study included researchers from University of Turku, Finland, the University of Gothenburg, Sweden, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

The study was funded by The Hartwell Foundation; National Institutes of Health Human Microbiome Project; the David and Lucile Packard, the Arnold and Mabel Beckman, the Ragnar Söderberg's, and the Päivikki and Sakari Sohlberg foundations; the Cornell Center for Comparative Population Genomics; and the Academy of Finland.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe