Worms hijack development to foster cannibalism

By Bridget Rigas

Conventional wisdom holds that genes determine the shape and structure (morphology) of animals, but something else may be at play. A new study shows that a roundworm (P. pacificus) regulates its offspring's morphology by using a potent cocktail of small-molecule signals. Exposure to trace quantities of these chemically unusual molecules can turn genetically identical juveniles into very different types of adults.

The study, co-authored by Frank Schroeder of the Boyce Thompson Institute for Plant Research at Cornell and Ralf Sommer of the Max-Planck Institute in Germany, was published in the Dec. 14 issue of Angewandte Chemie, a peer-reviewed journal ofthe German Chemical Society.

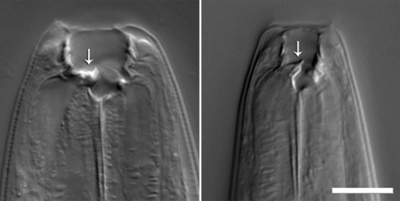

Schroeder investigated the development of the nematode P. pacificus, which can either have a narrow or a wide, large-toothed mouth. The wide-mouthed form had been shown to be associated with low food availability and facilitates a predacious lifestyle: These worms are well equipped to kill and eat other nematodes.

Schroeder and Sommer showed that under crowded conditions, the worms produce small-molecule signals that trigger development into the wide-mouthed form. These signaling compounds are part of a complex mixture of chemicals that regulates several additional aspects of worm development, including entry into an extremely long-lived and persistent larval stage.

But the developmental properties of these worm-derived chemicals were not the only unexpected findings. "What fascinated us most were the chemical structures of the compounds we identified -- they look like something from a chemistry lab, not like natural products," Schroeder said.

For example, one of the identified signaling molecules is based on an unprecedented type of nucleotide. Nucleotides are crucial components of all living organisms as they form the building blocks of RNA and DNA; known variations are based exclusively on the furanose form of the sugar ribose.

Schroeder and Sommer showed that P. pacificus produce the previously unknown xylopyranose form of an evolutionarily highly conserved tRNA residue. By combining this xylopyranose-based nucleoside with a lipid-derived side chain and L-paratose, a sugar also not previously found in nature, the worms create a highly potent and specific chemical signal that regulates development of their offspring. By identifying these compounds, the researchers showed that nematodes can combine building blocks from diverse metabolic pathways into complex chemical architectures.

Furthermore, this research suggests that structures of yet unidentified signaling molecules in higher animals, including humans, may deviate significantly from established paradigms, the researchers noted, emphasizing the need for a comprehensive investigation of human signaling molecules and their structures.

The research was funded by the National Institutes for Health and the Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology in Tuebingen, Germany.

Bridget Rigas is director of external relations and development at Boyce Thompson.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe