First black Law School grad was a former slave

Serendipity has revealed that George Washington Fields, Class of 1890, Cornell Law School’s first African-American graduate and one of the first black men to graduate from Cornell, is the only ex-slave ever to graduate from the university.

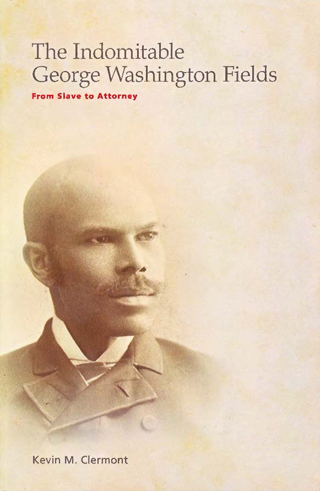

Fields (1854-1932) is the subject of a new book, “The Indomitable George Washington Fields: From Slave to Attorney,” by Cornell’s Kevin M. Clermont, the Ziff Professor of Law.

Clermont discovered Fields’ unpublished autobiography in the archives of the Hampton History Museum in Hampton, Va. Fields became a subject of interest for Clermont after reading his 1890 thesis arguing for the abolition of trials by jury. Clermont disagreed with Fields’ position but found his arguments intriguing, which led Clermont to learn more about him.

The unpublished manuscript convinced Clermont that “Fields’ autobiography constitutes a major contribution to the impassioned literature of North American slave narratives. Like ‘Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave’ (1845) and Booker T. Washington’s ‘Up From Slavery’ (1901), Fields delivers – along with considerable literary value – a feel for the realities of slavery that third-party accounts could never achieve.”

Born into slavery in Hanover County, Va, Fields made a historic escape with his family to Hampton 150 years ago at the height of the Civil War. He worked to support the family and pursue his education at Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute (now Hampton University). Later going north, he worked for nearly a decade, including stints as a manservant for, among others, New York Gov. Alonzo Cornell, before entering law school. After completing his legal studies, he returned home to Hampton where – though blinded in 1896 – he became a leading attorney in the region.

“Fields recounts his story of escape and triumph with a special blend of humor and wisdom, laying out in no uncertain terms the set of values that guided him through his fascinating times,” says Clermont. “Relating his march from slavery to a successful career as a blind lawyer, the autobiography convinces any reader that this was a great (and greatly likeable) man – and that his mother truly was a great woman.”

Fields’ life story comprises five acts: the wrenching antebellum life of a slave family, a dramatic escape during wartime, the rebuilding of family life during the South’s Reconstruction, the move to the North for more work and schooling, and finally the return to Hampton for a largely happy and productive life.

There were small parts of Fields’ manuscript that required decoding. “He was blind, and some of it was gibberish,” Clermont said, “but if you look at the keyboard and decide his fingers are one to the left of home key, you can decode it.”

Clermont’s book includes Fields’ decoded autobiography, his law thesis and a summary by Clermont that offers historical context and additional research about Fields’ life and his association with Cornell.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe