Electric fish may have switched from AC to DC

By Krishna Ramanujan

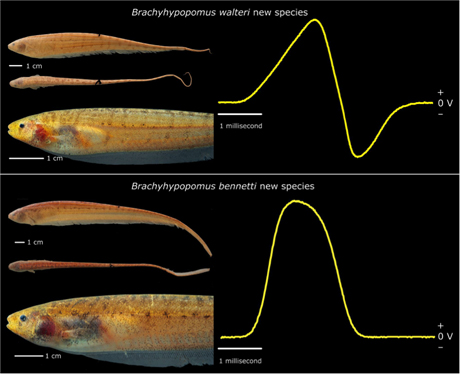

Two very similar species of Amazonian electric fish share a key difference: One uses direct current (DC) and the other alternating current (AC), according to research that formally describes the two species for the first time.

The paper was published Aug. 28 in the open-access journal ZooKeys.

Until now, the two types of knifefish were often mistaken for each other and placed together in fish collections. Both communicate with weak electric discharges and “electrolocate” – special receptor cells in their skin can pick up distortions in electric currents made by objects in the water.

The researchers report that one of the species, Brachyhypopomus bennetti, has a large electric organ and a short fat tail and produces direct current, or a monophasic, signal; the other, Brachyhypopomus walteri, has a more typical electric organ, a long thin tail and an alternating current, or biphasic signal.

“The most striking differences between these two similar species have to do with their electric organs and their electric organ discharges,” said lead author John Sullivan, curatorial affiliate at the Cornell University Museum of Vertebrates.

Most electric fish, like B. walteri, produce pulse-type, alternating current (AC) signals that sound like “pop-pop-pop” when recorded underwater, said Sullivan. These biphasic charges alternate currents of positive and negative volt phases, which cancel each other out in the water and may “cloak” such fish from predators that possibly hunt by sensing electric currents, said Sullivan.

The more rare type of signal, exhibited by electric eels and B. bennetti, consist of only a positive, monophasic pulse in which the direct current (DC) is not canceled out.

Macaulay Library to add sounds of electric fishes and more

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Macaulay Library, the world’s oldest and largest repository of animal audio and video recordings, is about to get even larger thanks to a four-year, $2 million grant from the National Science Foundation’s Advancing Digitization of Biological Collections program.

The grant will allow the library to add recordings of birds, frogs, insects and electric fishes from biological expeditions. Also, new recordings and some 7,000 archived sounds will be cross-referenced with physical specimens of species that made the sounds, along with video and images, where available.

For example, Carl Hopkins, professor of neurobiology and behavior, specializes in communication in fish with weak electric signals, and he and his colleagues have collected thousands of recordings and specimens of electric fish over 30 years. The recordings will now be added to Macaulay Library’s holdings with links to specimen records, field notes and photographs from the Cornell University Museum of Vertebrates. The museum boasts one of the world’s best collections of electric fish specimens, thanks to the Hopkins lab.

All of B. bennetti’s relatives, including B. walteri, have biphasic electric signals. “For that reason, we know that this trait evolved in B. bennetti’s lineage,” said Sullivan. “The interesting question is why.”

In 1999 a Florida International University researcher suggested that B. bennetti may be mimicking the electric eel, which has a powerful charge for stunning prey and protecting itself, but also a weak charge for electrolocating and communicating. The signal of B. bennetti closely matches that of the electric eel. This type of mimicry, where a benign creature mimics the appearance or qualities of a noxious organism, is called Batesian mimicry. For example, viceroy butterflies mimic the colors of foul-tasting monarchs, or benign marmalade hoverflies flies look like black and yellow wasps.

But Sullivan and paper co-authors, Jansen Zuanon of the National Amazonian Research Institute in Manaus, Brazil, and Cristina Cox Fernandes of the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, propose another theory: B. bennetti lives beneath floating meadows of water hyacinths and other plants, which exposes them to predation. Almost all the fish the researchers caught had parts of their tails bitten off, which eventually regenerate. For those fish with a biphasic current, the negative part of the charge comes from the tail. As a result, the researchers speculate, switching to a monophasic signal may help them to communicate and electrolocate in spite of tail damage.

“Having a signal that is more robust to tail damage is advantageous to these fishes,” said Sullivan, adding that the two hypotheses may both be true, but experiments need to be done to prove them.

The study was funded by the National Science Foundation and the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico in Brazil.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe