New book on how William III earned political trust

By Susan S. Lang

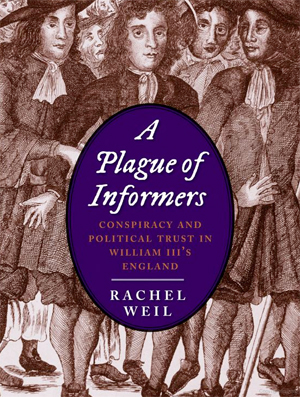

Stories of plots, sham plots and the citizen-informers who discovered (or fabricated) them are at the center of a new book by Cornell history professor Rachel Weil. “A Plague of Informers: Conspiracy and Political Trust in William III's England” (Yale University Press) looks at the turbulent decade following the Revolution of 1688, the so-called “Glorious Revolution” in which James II of England was overthrown by his daughter Mary and her husband, William of Orange.

“The book focuses on men and women, often of low social status, who claimed to have discovered plots against the government in the period after the Revolution of 1688,” says Weil, who specializes in the political and cultural history of early modern England. “The credibility of these informers and the treatment of persons suspected of disloyalty to the new regime were matters of fierce debate in the period. These debates, I argue, played into wider concerns about how to determine trustworthiness, about who could speak out on matters of political importance, and about how a revolution that justified itself as having restored the subjects’ liberty should handle the problem of security.”

Whereas most books about the Glorious Revolution focus on its causes or long-term effects, Weil says her book “zeroes in on the early years when the survival of the regime was in doubt in order to illuminate the painful tension between liberty and security, and the difficulties faced by the fragile new government as it tried to inspire trust in itself.”

As Weil explains, “By encouraging informers, imposing loyalty oaths, suspending habeas corpus and delaying the long-promised reform of treason trial procedure, the Williamite regime protected itself from enemies and cemented its bonds with supporters, but paradoxically also undermined its credit, raising doubts about whether it could live up to its promise to protect the liberty of English subjects. The modern world’s experience of post-revolution has shown that ‘regime change,’ even when meant to bring about a more liberal order, is never easy. I wanted to bring to life a post-revolutionary experience that is less ‘glorious’ but far more recognizable and resonant in our own time.”

“Rachel Weil is one of the very few most creative historians of early modern Britain,” writes Steve Pincus, a Yale professor of history. “In ‘A Plague of Informers,’ … a carefully argued and engaging narrative, Weil demonstrates what new regimes, no matter their commitment to ‘liberty’ however defined, have to generate trust from their subjects by dealing with those who do not share in their definitions of liberty and security.”

The 360-page book includes 15 black-and-white illustrations and is intended for general readers as well as students and scholars in English, history and political science.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe