Book uncovers challenges for Indonesian mine

By Linda B. Glaser

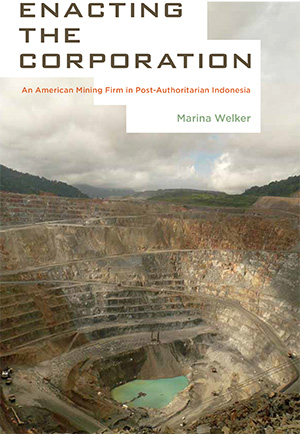

What is a corporation? To whom is it responsible? Marina Welker, associate professor of anthropology, explores these and related questions in her new book, “Enacting the Corporation: An American Mining Firm in Post-Authoritarian Indonesia,” an ethnographic study of the Denver-based Newmont Mining Corp. and its Batu Hijau Copper and Gold Mine in Sumbawa, Indonesia.

Welker, of the College of Arts and Sciences and a member of the Southeast Asia Program, explores the ethical relationship between business and society. In her book, she examines Newmont’s practices in light of the Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) industry, which advocates for voluntary social and environmental codes of conduct and practices among corporations. Her project examines the competing ways in which corporate managers, Sumbawan village residents, NGOs and government officials negotiate the social responsibilities of a mining corporation.

For her fieldwork in Denver, Welker had access to the company’s intranet and sat in on senior executive meetings where corporate strategies and projects were decided. “I felt as if I were in the very heart of the corporation,” says Welker—unusual access for an anthropologist.

The company’s approach to CSR, Welker reports, was to try to develop “socially responsible” relations with surrounding communities. This ranged from subsidizing meals for breaking fast during Ramadan to providing trash cans for villages (though not trash collection, a sore point with the locals). Environmental activists term Newmont “Newmonster” for its consumption of massive resources and generation of massive amounts of waste. The Batu Hijau mine pumps 160,000 tons of mine waste daily into the oceans.

But Newmont says it dumps three kilometers offshore and doesn’t use risky chemical reagants, Welker describes, in their effort to convey there is little danger associated with the dumps.

The company also emphasizes the environmental problems caused by the Indonesians themselves, such as their destruction of the coral when they collect sea worms, sea urchins and turtle eggs for food, and strives to instill care for the turtles in the villagers. They even sponsored an Earth Day art competition, says Welker. Unfortunately – for Newmont, at least – the winning entry depicted a factory dumping pollution in the ocean.

Each of Welker’s chapter titles includes a quote from one of the people in her study, ranging from “My Job Would Be Far Easier if Locals Were Already Capitalists” to “We Identified Farmers as Our Top Security Risk.”

That security risk, explains Welker, was labor-related: Newmont’s mine employed only 4,000 people at a time of severe economic downturn in the region. Those wanting employment would block the mine’s road with burning tires, costing Newmont a million dollars a day, until the company offered a new project to employ more people.

“The company had a travel advisory posted that warned mine employees how dangerous the locals were on any given day,” says Welker, who lived in local villages while doing her field research.

Welker’s latest project involves a clove cigarette corporation and commodity network, also in Indonesia, focusing on tobacco farmers, Javanese factory workers, urban and rural vendors, consumers, corporate managers and anti-tobacco activists.

Linda B. Glaser is a staff writer for the College of Arts and Sciences.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe