State of the Birds report shows success and need for conservation

By Hugh Powell and Krishna Ramanujan

The 2014 State of the Birds Report – an assessment of the health of the nation’s birds by some of the country’s leading experts released Sept. 9 – came with good news and bad news.

The good news is that conservation works, with bird populations recovering in areas where people have made strong conservation efforts, such as wetlands.

The bad news is that populations are down in many key habitats where conservation has lagged, with the steepest population declines occurring in arid land habitats of the West, followed by grassland and forest species. Arid land birds of Utah, Arizona and New Mexico, for example, have declined by 46 percent since 1968.

The State of the Birds report was created by 23 of the nation’s top bird science and conservation groups, with the Cornell Lab of Ornithology playing a lead role. This year’s report acknowledges the Sept. 1 centenary of the extinction of the passenger pigeon, which once numbered in the billions but were market-hunted into the grave, a reminder that even the most plentiful species can be lost without careful attention.

The report identifies birds as key indicators of ecosystem health by examining population trends of species dependent on one of seven habitats: grasslands, forests, wetlands, ocean, arid lands, islands and coasts.

The report reveals that:

Conservation works: Though threatened, declines of grassland birds have leveled off since 1990, due to significant investments in grassland bird conservation; wetland conservation has reversed the declines of waterfowl; coastal wetland restoration has provided resilience during major storm surges.

People must keep common birds common: Taking a lesson from the passenger pigeon, the report identifies 33 common birds in steep decline. These include such species as the northern bobwhite quail, grasshopper sparrow and bank swallow. Download a PDF of Common Birds in Steep Decline.

There are 228 species on the Watch List: The Watch List includes federally endangered or threatened species, plus species that showed signs of severe population declines in the report’s analysis of long-term (1966–2012) population data. Download a PDF of the Watch List.

Key habitats in danger: Along with the West’s arid lands, birds in clear and present danger include the native forest birds of Hawaii, the seabirds of the open ocean, the grassland birds of the middle of the continent and coastal shorebirds.

Citizen science data is priceless: The 2014 report analyzed decades of data from the Christmas Bird Count and Breeding Bird Survey to measure trends for hundreds of bird species – all data provided by enthusiastic, skilled, volunteer birders. The Cornell Lab’s eBird project is an example of such an initiative.

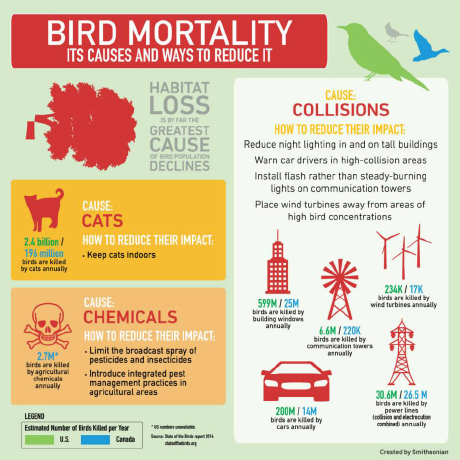

People are beginning to understand what works: A few specific actions, broadly applied, benefit bird populations in many places, according to the report. Habitat loss is the No. 1 cause of declining populations; conservation and restoration are key. Other problems include energy development, recreation in sensitive habitats, the introduction of invasive species and climate change.

The project lead was Alison Vogt of the Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies. Cornell lab participants included Ken Rosenberg, who chaired the science team; Gus Axelson, who edited the report; Ashley Dayer, who served on the communications team; Joanne Avila, who designed the report; and Stef den Ridder, a Bartels Science Illustration Intern, who painted the cover illustration.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe