Cornell Rewind: A great school faces the Great War

By Elaine Engst and Blaine Friedlander

“Cornell Rewind” is a series of columns in the Cornell Chronicle to celebrate the university’s sesquicentennial through December 2015. This column will explore the little-known legends and lore, the mythos and memories that devise Cornell’s history.

In early 1917, fighting raged in Europe. German submarines prowled the Atlantic shipping lanes, and Germany secretly had tendered to Mexico a partnership offer to wrest Texas, Arizona and New Mexico back from the United States. U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, Congress and the American people could no longer avoid joining the Great War, the conflict that would become World War I.

Wilson signed the Congressional declaration of war April 6, 1917, and scarcely a week later about 575 Cornell male undergraduates registered for military service.

In fact, Cornellians already were participating in the war effort. In October 1914, Mary Merritt Crawford, Class of 1904, M.D. 1907, went to France to serve as a “house surgeon” in the American Ambulance Hospital at Neuilly-sur-Seine. Anna Irene von Sholly, M.D. 1902, also received a lieutenant’s commission in the French Army.

Edward Tinkham, Class of 1916, left Cornell early and drove an ambulance in France. For his extraordinary heroism at Verdun, Tinkham was awarded the Croix de Guerre. He returned to Cornell in 1917 to finish his degree and organized a Cornell unit in the American Ambulance Field Service. When the unit arrived in France on April 14, 1917, the U.S. had joined the war, and the group eventually transferred to an American Motor Transport Unit. Commanded by Tinkham, this was the first American fighting unit to carry the American flag to the front.

The aviation ground school takes flight

Back on campus, students, faculty and administrators had signed a petition asking the U.S. War Department to establish an aviation ground school at Cornell. The petition was granted – and the U.S. Army School of Military Aeronautics at Cornell University was born. Cornell became one of six universities to host a ground school.

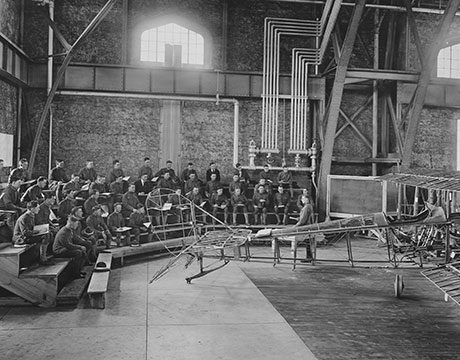

Cornell’s first class of soon-to-be pilots arrived May 17, 1917. Buzzers for wireless (radio) practice were installed in the basement of Schoellkopf Hall. The pilots received engine class training in Rand Hall, and physics professor Ernest Blaker, Ph.D. 1901, held classes on flight theory, meteorology and radio work.

Army Capt. F.G. Page visited Cornell’s ground school in mid-June and declared, “After a period of three week’s work, Cornell compares favorably indeed with the flying school at Toronto, and in some respects, is well ahead of it.”

Applicants to the ground schools – one merely needed to show up to gain admittance – grew beyond the originally allocated 25 students to about 200 at any given time.

Schoellkopf Hall, adjacent to the former Alumni Field, initially served as a barracks. James Edwin “Ted” Meredith, an Olympic gold medalist at the 1912 Stockholm games and the University of Pennsylvania’s quarter-mile and half-mile intercollegiate champion, “now hangs his clothes in a locker and sleeps on a bunk in the track dressing room of Schoellkopf Hall – war is full of surprises,” touted The Cornell Daily Sun. Meredith flew combat missions over Germany and returned home after the war.

With bulging enrollment, the aeronautics school outgrew Schoellkopf. Future flyboys – hundreds of them – had quarters at the new New York State Armory and Drill Hall, built in 1915 for $350,000. In 1940, the building was named Barton Hall in honor of Col. Frank A. Barton, Class of 1891.

‘…One of the most beautiful spots…’

For the pilots, final exams required comprehensive and skillful answers. In the engines class, students saw questions like “What are the advantages of [a] double ignition system for airplane motors?” or “How many times per second does the interrupter break the primary current of a magneto which is furnishing the ignition for an eight cylinder engine running 1400 rpm?” or “Make a sketch of a two-gear oil pump, showing path of oil and direction of rotation of gears.”

To achieve superior field intelligence, the Army needed aerial photography. Alongside the pilots, photographers trained at Cornell for reconnaissance missions, providing important images of revealed camouflage, decoy trenches, barbed wire and hidden batteries.

Lewis Lupton Kaylor was among the many aerial photographers. In a March 1918 letter to Ruth Smeltzer, he wrote of Ithaca’s natural splendor : “I stood out this evening at sunset, with all its glory, and I could hardly hold myself, for thinking of you. This morning, six of us went on a hike … this is one of the most beautiful spots in the world, Ruth, with so many waterfalls.”

Armistice and Cornell’s contributions

On Nov. 11, 1918, the war ended when armistice was achieved.

During World War I, Cornell provided 4,598 commissioned officers to the war effort, more than any other institution, including West Point. Cornellians earned at least 526 decorations and citations during the war, including several who received special distinction.

Five pilots became aces – with more than five victories each. Lawrence Kingsley Callahan, Class of 1916 and John Owen Willson Donaldson (attended Cornell 1916-17), flew for England’s Royal Air Force. Jesse Orin Creech (1916-17), James Armand Meissner, Class of 1918, and Leslie Jacob Rummell, Class of 1916, for the U.S.

Cornell women physicians also served, although the U.S. Army would not commission women doctors. As “contract surgeons,” they were not officers, and earned less than their male counterparts. They included Anne Tjomsland, Class of 1911, M.D. 1914, an anesthesiologist working at Bellevue Hospital in New York City, who served overseas; and Anna Kleegman, Class of 1913, M.D. 1916, and Gertrude Guild Fisher McCann, M.D. 1916, who worked stateside. Jean Harwood Pattison, M.D. 1919, volunteered at various hospitals including the French Hospital at Meaux and the American field hospital at Chateau Thierry.

Nurses were a different story. An all-female U.S. Army Nurse Corps had been founded in 1901; nurses could serve officially, and more than 10,000 were sent overseas during the war. Julia Catherine Stimson, who graduated from the New York Hospital Training School for Nurses (a predecessor of the Cornell University-New York Hospital School of Nursing), became director of nursing for the American Expeditionary Force. She was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal, and after the war she became superintendent of the Army Nurse Corps and the first woman to attain the rank of major in the U.S. Army. In 1918, the U.S. War Department created the Student Army Training Corps (S.A.T.C), the predecessor to today’s ROTC.

Today, there are no barracks in Barton Hall, and pilot and aerial photography classes vanished close to a century ago. But as an everlasting tribute to the brave souls who walked these grounds, the War Memorial, on West campus, dedicated in 1932, commemorates Cornell’s 264 World War I casualties.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe