Cornell Rewind: Phenomenal first women of engineering

By Elaine Engst and H. Roger Segelken

“Cornell Rewind” is a series of columns in the Cornell Chronicle to celebrate the university’s sesquicentennial through December 2015. This column will explore the little-known legends and lore, the mythos and memories that devise Cornell’s history.

Women were unusual in engineering at Cornell and nationally, and more was expected of them. Kind of like Ginger Rogers doing everything Fred Astaire did, backwards and in high heels, Cornell’s pioneering, engineering women – Kate Gleason, Nora Stanton Blatch and Olive Wetzel Dennis – advanced the science of their discipline beyond all expectation of their male peers.

Cornell taught engineering from the very beginning in 1868. The Morrill Act required the land-grant universities to teach the mechanical arts and Cornell’s charter reflected it. Both the Morrill Act and the charter were gender-neutral in their choice of words, using the terms “persons,” “applicants” and “students.” Many of the early male students came to Cornell to study mechanical and civil engineering. While the first woman graduated from Cornell in 1873, women are surprisingly absent from the early engineering courses; instead they studied math and science.

‘Sibley Kate’

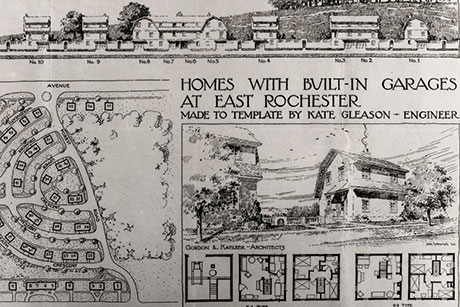

According to the story, Kate “Sibley Kate” Gleason (1865-1933, Class of 1888), Cornell’s first woman mechanical engineering student, wore overalls and packed a worker’s lunch pail for her walk between the Sage Hall women’s residence, across the quad, to Sibley Hall, home of the School of Mechanic Arts, during her years on campus, in 1884-85 and 1888. The Rochester-born Gleason led a remarkable life as a female industrialist, banker, inventor, land developer and celebrity – going global with the Gleason family business; building innovative-yet-affordable housing of reinforced concrete; becoming the “First Lady of Gearing,” the “Marie Curie of Machine Tooling,” a leader (and the first woman member) in the American Society of Mechanical Engineering, and the self-styled “Most Famous Woman in France.”

Forced to drop out of Cornell and return to Rochester, during the 1880s financial crisis, to work in the family business, Gleason recalled: “My heart broke utterly. I took Father’s letter out on the campus and sat under a tree... and wept and wept. I had planned to finish the engineering course. I was the only woman and it meant so much.”

Gleason did come back as a “special student” in 1888 and returned repeatedly to Ithaca throughout her career to stay active in alumni affairs, running unsuccessfully for election to the Board of Trustees in 1916. In 1914, she met with Andrew Dickson White, who wrote in his diary: Thursday, May 7 … Pleasant time with Miss Katherine [sic] Gleason of Rochester (“Sibley Kate”), showing her through Risley Hall… She is a wonderful woman, managing admirably a vast business and very attractive in every way.”

She also took the advice of her mother’s friend, Susan B. Anthony, and traded her overalls for a proper lady’s dress, including the flamboyant hats that became her trademark. Lacking a college degree but with notable accomplishments around the world, she repeatedly said engineering was one profession where a woman could achieve career equity. When Gleason built a new golfing community near Rochester, she gave a first job – as caddy master – to a local boy who also attended Cornell: Robert Trent Jones ‘30.

Gleason’s personally designed home in Sausalito, California (the affordable homes for workers were mostly in Rochester, New York) clung securely to such a steep hillside that the garage was in the attic. Concrete savvy will do that.

‘Better than many male seniors’

Nora Stanton Blatch (1883-1971, Class of 1905), the granddaughter and daughter, respectively, of suffragists Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Harriot Stanton Blatch, became the first woman in the U.S. to receive a degree in civil engineering. At Cornell, Blatch was a member of Kappa Kappa Gamma sorority; Raven and Serpent (Junior honorary society); Der Hexenkreis (Senior honor society); Deutscher Verein (German Club); and the Cornell Political Equality Club. She managed the Women’s Fencing Club, and was elected to Sigma Xi, the honorary scientific society founded at Cornell in 1886. Blatch‘s research in the Beebe Lake hydraulics laboratory for her civil engineering thesis, “An Experimental Study of the Flow of Sand and Water in Pipes under Pressure,” solved a key problem in hydrodynamics.

Although a woman, Blatch was allowed to participate in the Summer Surveying Camp required of all civil engineers. In a recommendation letter, her professor, Ernest William Schoder wrote: “Objections to the presence of a woman in a field such as you would organize can hardly be as great as the objections to the presence of a woman in the Cornell Junior Class survey camp. Miss Blatch went through the latter experience and I think that her powers of adaptation were not over taxed at all. She can use her hands and head, separately and together, better than many male seniors.”

As the only woman in the 1905 civil engineering class approached the dais on graduation day, hundreds of onlookers stamped their feet in unison. “My fellow students simply couldn’t give up teasing,” Blatch thought – mistakenly, as it turned out. “President Schurman showed special honor to me by stepping forward and bowing” as he awarded the first-of-its-kind diploma.

“I started back to my seat fully expecting another demonstration of tramp, tramp,” Blatch wrote decades later in an unpublished memoir, “but complete silence reigned.” Then came the applause.

In 1908, Blatch married Lee De Forest, an inventor and radio pioneer. While honeymooning in Paris, she lugged her husband’s new-fangled radio gear up the Eiffel Tower and broadcast greetings to afar. Back in New Jersey – even with her education in math and electrical engineering the “Father of Radio” lacked – she couldn’t get a job running his capacitor factory.

When she ultimately sued him for divorce, De Forest told the New York Times their marriage failed because Nora was “all mentality and ambition.” Worse yet, she “persisted in following her career as a hydraulic engineer and an agitator.” The story was headlined “Warns Wives of Careers.”

Blatch started with bridges, and helped build subway tunnels in New York, working for the American Bridge Company and the New York Water Supply System. She remained active in the campaign for women’s rights, serving as chair of the National Advisory Council of the National Woman’s Party. She later remarried - marine engineer Morgan Barney, a man who could appreciate her talents - and built some of the finest homes on Connecticut’s Fairfield County “Gold Coast.” While she was a member of the Cornell Society of Civil Engineers, she never could gain admittance to the all-male American Society of Civil Engineers.

The walls of her Greenwich home lacked one customary souvenir of Cornell civil engineering: a framed class picture from the summer surveying camp. Her male classmates had arranged a date for her that August afternoon, then snapped the picture without her.

‘The Engineer of Service’

Cornell’s second woman to graduate with a civil engineering degree, Olive Wetzel Dennis (1885-1957, Class of 1921), made train travel comfortable and fashionable, giving riders what most could only wish for at home: air conditioning, bright upholstery on reclining seats, gourmet meals (locally sourced wherever the train went) on the railroad’s finest china, which “The Engineer of Service”(as she was called) designed.

After graduating from Goucher College in 1908, and receiving a master’s degree from Columbia University in 1909, Dennis taught mathematics in Washington, D.C. for 10 years. In 1919, she came to Cornell, receiving her civil engineering degree in only one year. Dennis got her first job building railroad bridges in rural Ohio – in the winter – with this boast: “I helped lay out the railroad line at Ithaca last December and I am rather anxious to get out on the road again. There is no reason that a woman can’t be an engineer simply because no other woman has ever been one. A woman can accomplish anything if she tries hard enough!”

She went to work as a draftsman for the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, eventually becoming a research engineer, working for the railroad until her retirement in 1951. During World War II, she served as a consultant for the federal Office of Defense Transportation. Dennis was the first woman admitted to the American Railway Engineering Association.

In a 1951 New York Times article, she reminisced: “Sometimes, my assignments would require my riding with the engineer of a locomotive during speed and safety checks. But I never took advantage of being a woman.” She was not always accepted into the “ranks of track officialdom” by the executives of other lines. “The worst snag was when the B. & O. asked another road for a pass for her. It came back made out to ‘Oliver Dennis.’ Returned with the notation that it should have been issued to ‘Miss Olive Dennis,’ it was changed to read, ‘Miss Olive Dennis, daughter of Engineer Oliver Dennis.’”

By 1945, a total of 19 women had graduated from Cornell’s College of Engineering. The Cornell Society of Women Engineers, founded in 1972, promotes women in engineering through programs, professional development and academic support. Currently 38 percent of Cornell engineering undergraduates are women, while the average at other undergraduate engineering colleges is 18 percent. Nationally, women make up 23 percent of graduate student population at engineering schools, while at Cornell that number is 29 percent.

Kate Gleason, Nora Stanton Blatch and Olive Dennis would undoubtedly be amazed and thrilled by the transformation of the college and the profession that was so important to their lives and careers.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe