Library returns rare science book stolen in Sweden

By Daniel Aloi

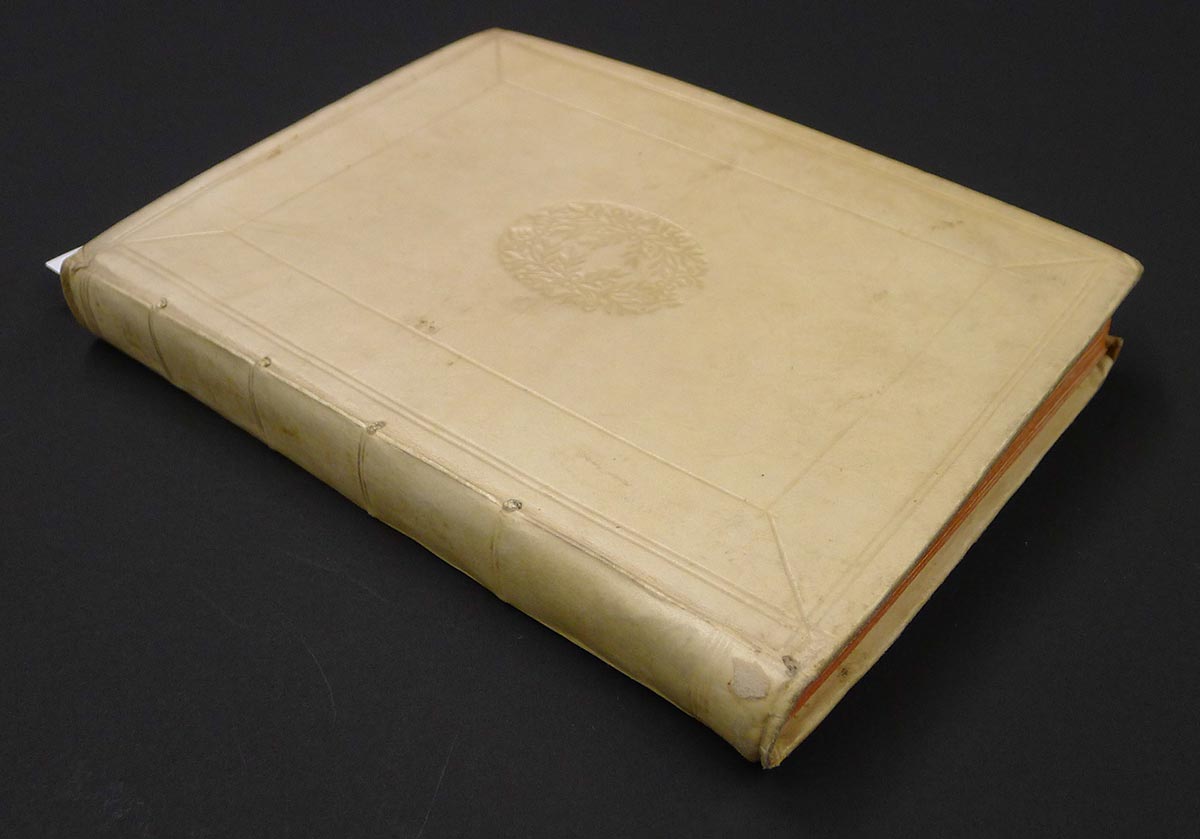

David Corson has seen thousands of rare scientific texts in his career at Cornell University Library, but none with quite as much intrigue attached as “Oculus hoc est: Fundamentum opticum,” Bavarian physicist Christoph Scheiner’s 1619 book on optics and the physiology of the human eye that led to the development of corrective lenses.

In June 2012 Corson learned that Cornell’s copy of the book, purchased in 2001 and one of about 60 copies in existence, possibly had been stolen from the National Library of Sweden (NLS) in the 1990s. After a lengthy effort to verify the book’s provenance, it was returned at a reparation ceremony June 16 at the U.S. Attorney’s Office in lower Manhattan.

Corson attended the ceremony along with David Bannon, a Cornell parent who led a technical analysis of the Scheiner book in Kroch Library last year; Jonathan Hill, the New York book dealer who bought “Oculus” at auction and sold it to Cornell; and Sweden’s national librarian, Gunilla Herdenberg.

Neither Hill nor Corson knew of the book’s illicit history until 2012.

“No reputable dealer will ever buy or sell anything that is of questionable provenance,” said Corson, the recently retired curator of the History of Science Collections in the library’s Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections. “Dealers will return any book that is known to be stolen. The problem for us or any institution is, if you come to me and say, ‘That book that you have was stolen from me 10 years ago,’ I have an obligation to my institution to be absolutely sure that this story holds water.”

The story of the book’s theft and return, he said, “spans the gamut from international skullduggery to the application of cutting-edge technologies being developed in totally unrelated fields.”

NLS manuscript librarian Anders Burius allegedly stole at least 56 rare and valuable books from his employer between 1995 and 2004, and sold them under an assumed name through a German auction house – among them a 1633 book of poems by John Donne, philosopher Thomas Hobbes’ 1651 “Leviathan” and a 1619 work by astronomer Johannes Kepler. Several books went to buyers in the United States, according to the FBI. Burius committed suicide in Stockholm in 2004, after his confession and arrest for the thefts.

“This was a crime of opportunity,” Corson said. “He not only stole the books but he erased all the records indicating NLS ownership. What tripped him up was, a researcher came into the Swedish library and already had the call number for a book because he’d used it before – and that book wasn’t there when it was paged. And that is literally how it started to become unraveled.”

As the NLS investigation continued in the years since Burius’ arrest and death, the FBI contacted Hill in June 2012, and he contacted Corson. An FBI agent specializing in cultural property losses mediated as the two libraries tried to determine that the Scheiner book in Cornell’s possession was the one stolen. All provenance information had been chemically erased, including “all the library markings that would have absolutely identified this book,” Corson said.

Enter Bannon, whose company, Headwall Photonics, specializes in hyperspectral imaging technology that uses nonvisible light frequencies to gather and analyze data. While Bannon’s twin daughters Keelin ’14 and Mallory ’14 were Cornell students, he attended a talk in Boston by outreach and learning services librarian Lance Heidig on the Gettysburg Address, and later wrote to the library about using Headwall’s instruments to scan and learn more about Cornell’s books and documents, Heidig said.

Corson approached Bannon’s team when they visited the library in early 2014 with “a real-world application for this. They were very interested and they did some very significant analysis over a period of a year.”

The Scheiner book was exceptionally clean for its age, Corson noted. In the final report Headwall submitted in November, imaging including very near infrared (VNIR) analysis revealed faint traces of the call number, or shelf mark, “consistent with the way they mark books” at the Swedish library; and telltale paste residue inside the front cover. Through the FBI, Corson inquired if the NLS used bookplates, and requested photographs of some examples.

“We were able to correlate the paste residue with the size of their bookplates to within 2 millimeters,” he said.

The Scheiner book was thus convincingly documented as belonging to Sweden. Hill, the dealer who had purchased the book in 1999, obtained another copy and presented it to Cornell.

“To me it’s a very distressing story in terms of how it began, but in the end it’s pretty exciting with the new technology,” Corson said.

Most of the NLS’s missing books have yet to resurface. Only five stolen titles have been recovered from North America so far – a 1597 atlas of the Americas, in 2012; a 1638 work on theatrical design by Italian architect Nicola Sabbattini, bought by an unsuspecting Manhattan bookseller and returned with the Scheiner book in June; and two volumes on colonial America once owned by the Swedish royal family, returned at a similar ceremony in 2013.

The book’s return also capped a nearly 36-year Cornell career for Corson, who retired June 30. Curator of the History of Science Collections since 1979, he also filled administrative roles including director of Olin Library (1984-2001).

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe