NSF grant allows digitization of Cornell microfungi collection

By Krishna Ramanujan

A Cornell collection of tiny fungi – with specimens dating to the 1800s – will enter the modern age and go digital, thanks to a National Science Foundation (NSF) program to digitize biological collections across the country.

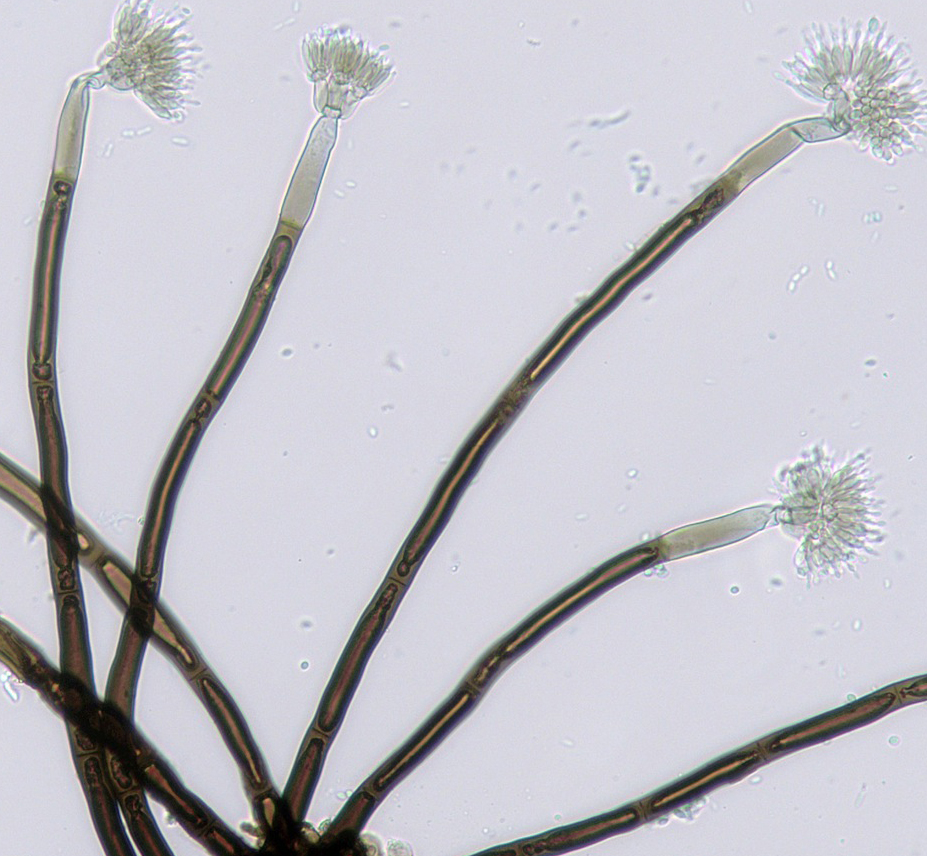

Microfungi are small molds, soil and water fungi, and Cornell holds more than 100,000 dried specimens in the Cornell Plant Pathology Herbarium, a research collection of 400,000 preserved fungi and other organisms that cause plant diseases. Cornell’s microfungi will be digitized as part of NSF’s Advancing Digitization of Biodiversity Collections program, which seeks to document America’s biological collections. Cornell already has received NSF grants to digitize its macrofungi and lichen collections.

NSF has granted $2.6 million to the Microfungi Collections Consortium of 38 institutions in 31 states. Within the consortium, Cornell and two partner organizations will receive $200,125.

The herbarium’s physical samples are stored in green cabinets in a newly renovated, permanent facility on Game Farm Road at the eastern edge of the Cornell campus.

Records of locations, dates when specimens were found and taxonomic information will be migrated along with photos of specimen labels into a searchable database.

“The beauty of this project is we are unlocking big data of where fungi occur in the world, and when,” said Kathie Hodge, director of the Cornell Plant Pathology Herbarium and associate professor of mycology. “All of this information locked up in cabinets will now be searchable across a database. If we are looking for what mushrooms grow in Ithaca in June, we can search that,” Hodge said.

For the first time, users will be able to synthesize information to gain insight on global biodiversity, climate change, ecology, invasive organisms and plant disease, she added.

The plant pathology herbarium includes specimens of Ophiostoma ulmi, the microfungus that causes Dutch elm disease, which was introduced accidentally to the U.S. in 1928 and has killed the majority of elms in the Northeast.

“We have a number of old, historical specimens, from the time when it took off in North America,” said Scott LaGreca, the herbarium’s curator. The samples have been used for their DNA to reconstruct the plant disease’s history and better understand how it spread, LaGreca added.

Other notable specimens include Inocybe olpidiocystis, a species discovered on the lawn of the A.D. White House on campus but not found anywhere else in the world, and microfungi from American explorer Robert Peary’s Arctic expeditions.

“The herbarium is like a library in that we routinely loan our specimens to researchers, sending them out via international post for examination,” said Hodge. “Unlike a library, though, almost every one of our specimens is unique and not duplicated anywhere else in the world.”

Digitizing the microfungi collection began this fall and may take a year to complete.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe