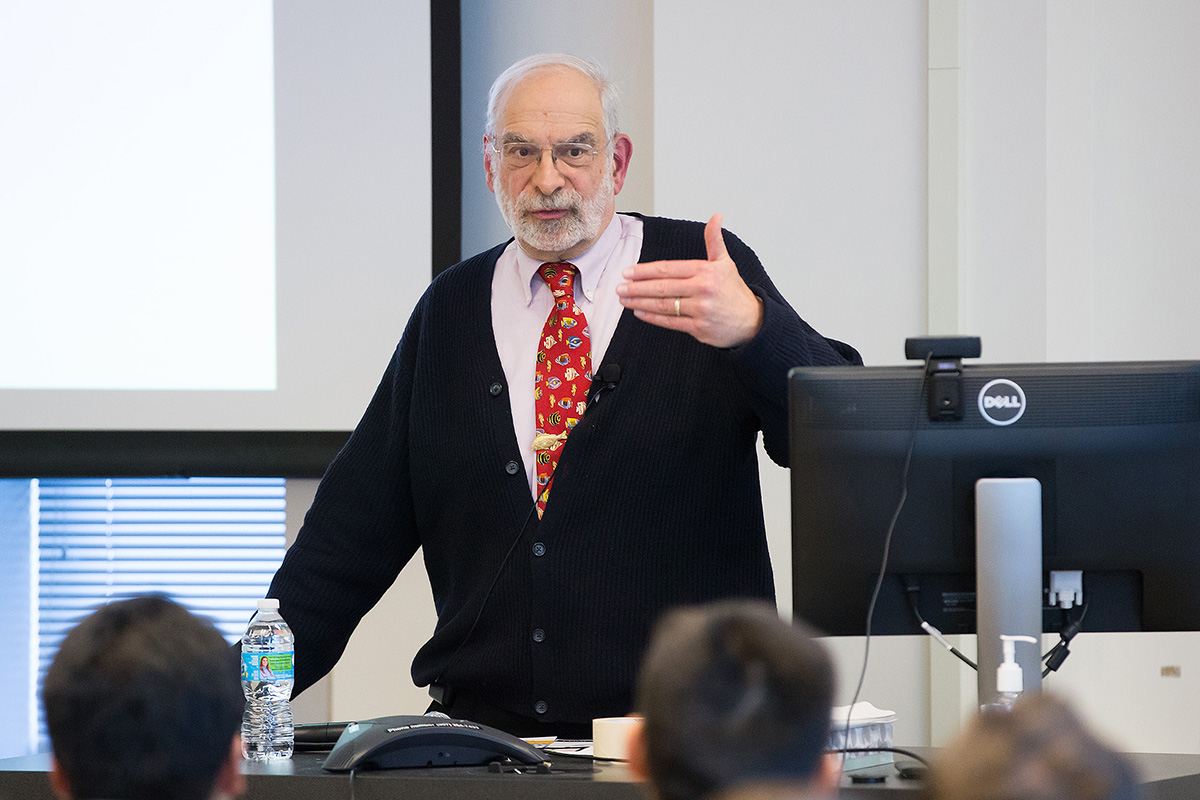

Joe Regenstein touts benefits of GMOs

By Amanda Bosworth

Consumer fears about genetically modified food are mostly misplaced, according to Cornell professor emeritus of food science Joe Regenstein ’65, M.S. ’66, who spoke to an audience of 70 at Mann Library Feb. 18.

After all, he said, agriculture has never been natural. Farmers have been breeding plants and animals for thousands of years, and breeding moves whole groups of genes around at once, in the form of chromosomes.

“The concept of a gene transferring is not a new concept,” Regenstein said.

Agriculture has often involved introducing animals to a new country or region, with their attendant microbes and diseases. This “classical breeding” is totally unregulated by the U.S. government, according to Regenstein. Today’s genetic modification is much more precise, as only one gene is manipulated at a time. If we can accept agriculture, we can accept genetic modification, he said.

“There ain’t nothing natural in most of our food supply,” Regenstein joked. He discussed his recent book, “Genetic Modification and Food Quality: A Down to Earth Analysis,” co-authored with Robert Blair of the University of British Columbia. Regenstein argued that domestication has always been a “reflection of human values,” so Americans should not assume that GMOs (genetically modified organisms), seemingly new on the scene, represent a departure from some mystical, ideal state of nature.

Genetic modification of plants is already helping farmers by increasing crop yields and reducing the need for harmful pesticides, helping consumers by increasing vitamin and nutrient content, and helping the planet by producing crops tolerant of drought and heat, he said. The first animal GMO in progress now is the “AquaBounty salmon,” a specimen that only differs from other salmon in that it grows faster. Ultimately, said Regenstein, “getting animals growing faster is good for the environment.”

He is skeptical of the recent American obsession with grass-fed animals. If cattle or sheep feed on grass only, they grow slowly. With grains or agricultural byproducts added to their diets, they grow faster and belch less methane into the atmosphere. Eating grass-fed meat is self-defeating in his view.

Regenstein is deeply concerned with the health and efficiency of our food supply, animal welfare and environmental sustainability. With a rapidly increasing global population, he argues, “A lot of the things that we need to maintain our food supply are probably going to require GMOs.”

If individuals still believe that they only want to purchase GMO-free food, Regenstein believes they have the right and should be prepared to pay extra for it – just as do consumers seeking kosher, halal or organic food. But in his view, there is no reason to be scared of GMOs.

The lecture was part of Cornell Library’s “Chats in the Stacks” series with faculty authors. Regenstein is also a member of the Jewish Studies Program, head of the Kosher and Halal Food Initiative and adjunct professor of population medicine and diagnostic sciences at the College of Veterinary Medicine.

Amanda Bosworth, a Cornell doctoral student in history, is a writer intern for the Cornell Chronicle.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe