Nobel laureate Alexievich created her own literary genre

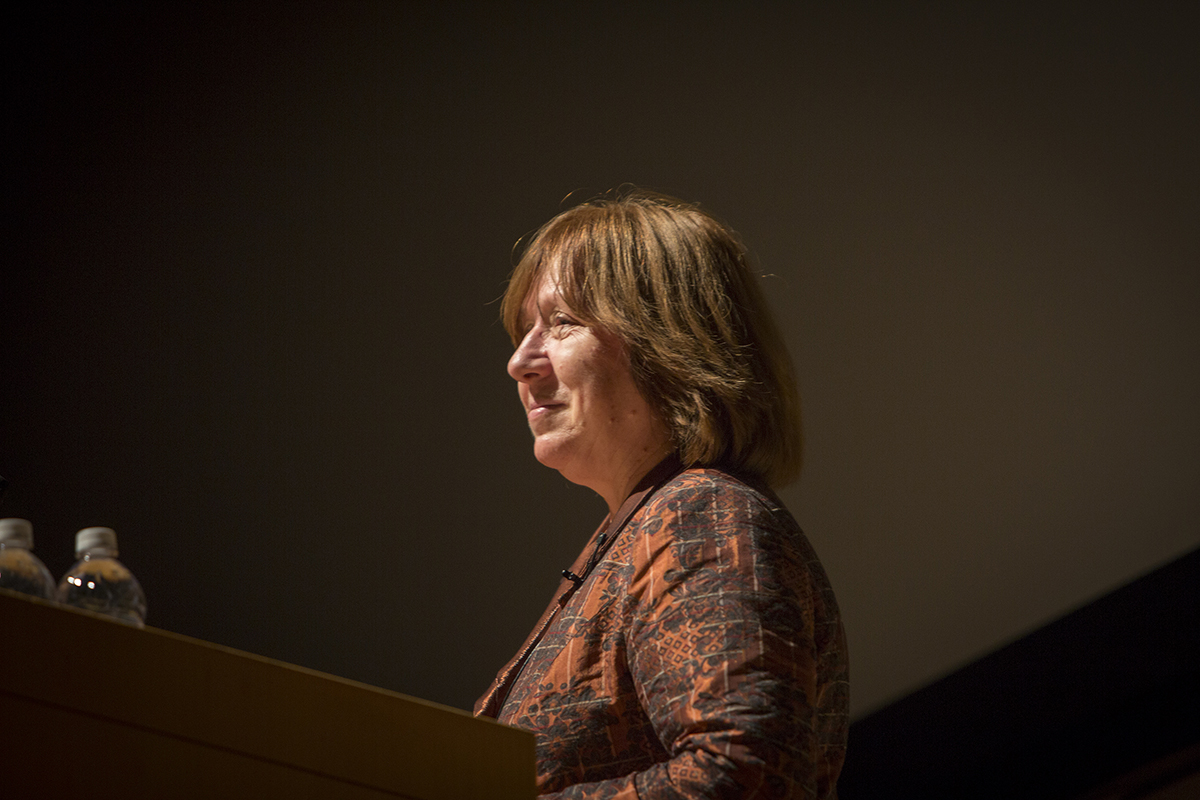

“I am a historian of the soul,” explained 2015 Nobel Prize winner Svetlana Alexievich at Statler Auditorium on Sept. 12. “History is often arrogant and dismissive of what is small and human. A whole choir sounds in my books.” The daughter of a Belarusian father and a Ukrainian mother, journalist and nonfiction writer Alexievich grew up in Belarus.

Alexievich was on campus as the 2016 Henry E. and Nancy Horton Bartels World Affairs Fellow. The Bartels program, sponsored by the Mario Einaudi Center for International Studies, brings prominent international leaders to Cornell to foster a broadened world view among Cornell students. Interim President Hunter Rawlings introduced Alexievich.

Alexievich has written books based on conversations with former female combatants in World War II, visits to Chernobyl after the 1986 nuclear plant accident and meetings with soldiers at the front in the Soviet-Afghan War. In her view, Afghanistan and Chernobyl buried the socialist empire, finally cracking the illusion that was the Soviet dream.

She was the first nonfiction writer to be awarded the Nobel Prize in literature in more than a half-century. In her lecture, “Voices From the People: The Rise and Fall of the Russian-Soviet Dream,” Alexievich described how she developed her unique literary style, a collage of human voices that collectively tell the story of tragedy. She determined to preserve the history that otherwise leaves no trace – the stories of average survivors.

Alexievich discovered texts and literature everywhere: in apartments, on the street and on the train. She explained: “I learned how to listen, how to turn myself into one big ear.” An entire day of conversation with one former Soviet citizen might only yield a single phrase. But, Alexievich marveled, “What a phrase!” Critics have noted that the voices in her books speak too beautifully to be believable. Yet she countered, “In love, and in contact with death, people always speak beautifully. At these moments they transcend their ordinary selves – they rise up on tiptoe.”

People have told Alexievich that what she writes is neither history nor literature; it is just life, “rubbish that the artist has not polished.” For her, however, “Shouts and sobs cannot be polished, or the main thing will be neither the tears nor the shouts, but the polish.”

Many of Alexievich’s books were censored in the Soviet Union, and later Belarus, for being unpatriotic or depicting soldiers negatively. With the onset of perestroika in the late 1980s, her subjects spoke much more openly or added to their previous stories. They often said to her, “I can tell you, because you’re Soviet, and only a Soviet person can understand another Soviet person – you know what I mean.”

Alexievich believes the dream of freedom introduced by perestroika failed because Soviet citizens did not know how to live as free people. No one toasting the onset of freedom imagined freedom as work. When she asks people whether they would prefer a strong country, or one in which people enjoy a good life, eight out of 10 people respond they would choose a strong country.

The packed auditorium in Statler Hall gave Alexievich a spontaneous round of applause when she stated, in reference to war: “Ideas should be killed, not people.” Her presentation was in Russian, and translation was provided by Raissa Krivitsky, senior lecturer in the Russian Language Program. Alexievich is working on two new books, one about aging and one about love.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe