After sunflower sea star demise, marine tragedy mounts

By Blaine Friedlander

Researchers from Cornell and the University of California, Davis, have begun to reckon the marine ecosystem devastation of the Salish Sea – north of Seattle – caused by a disease that led to the disappearance of once-abundant sunflower sea stars and other starfish over the past three years.

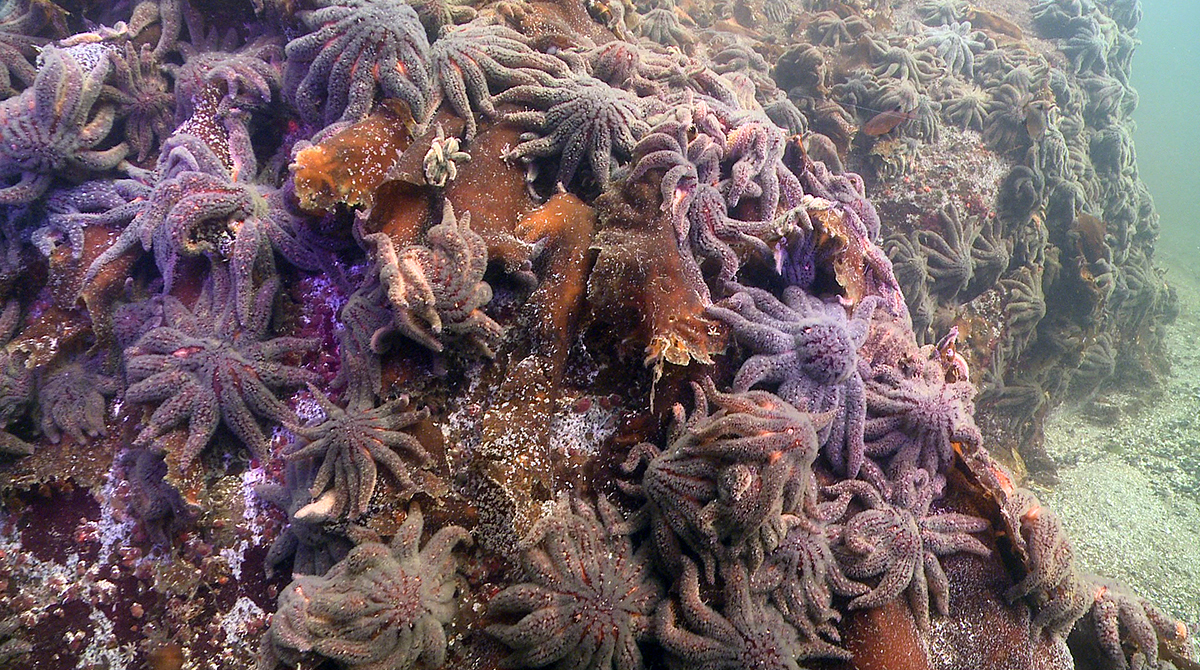

“The sunflower sea star was among the most common of subtidal sea stars. It was like a robin in our waters,” said C. Drew Harvell, professor of ecology and evolutionary biology. “You would see it all over the pilings. Divers would find it three, four, 10, 30 on a dive. It was everywhere. Some people thought it was a pest. It wasn’t.”

Using research data from the Reef Environmental Education Foundation, collected by trained citizen-scientist divers and long-term historical data, the researchers have assembled the scientific backstory of the aquatic disaster. Their findings are in a report, “Devastating Transboundary Impacts of Sea Star Wasting Disease on Subtidal Asteroids,” published Oct. 26 in the online journal PLoS One.

With a gluttonous appetite for sea urchins, snails and clams, the nimble and relatively speedy adult sunflower sea stars are large creatures with an arm span of up to 3 feet. In the Salish Sea, the sunflowers kept marine populations in balance.

“It’s a voracious predator; it eats everything. It was probably eating a lot of baby sea urchins,” said Harvell. But when sea star wasting disease struck in 2013, the large populations of sunflower sea stars (Pycnopodia helianthoides), which live below the tidal line, dwindled along with other starfish species and then disappeared.

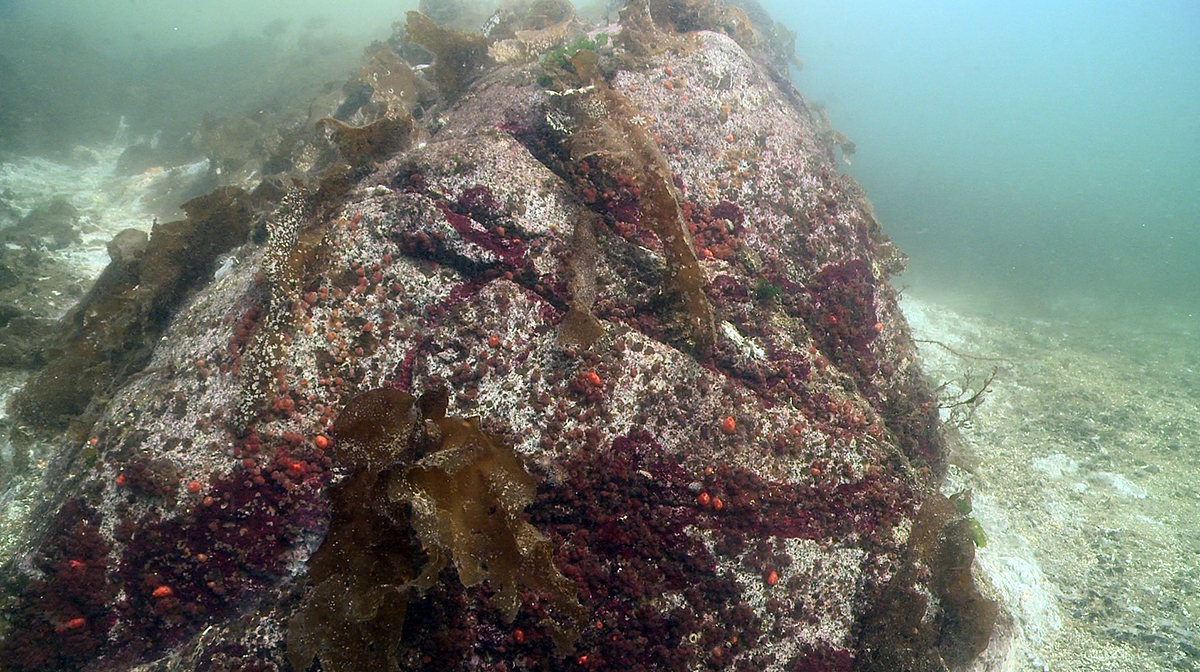

“Divers are reporting quite a few places now with sea urchin outbreaks,” Harvell said, who explained that with a massive urchin growth, underwater forests of kelp are being destroyed. Crustose algae are replacing the kelp – the start of an environmental downward spiral. While the sunflower sea stars are not a commercial edible species, it is a keystone species, contributing to a balanced marine ecosystem, she said.

The wasting disease has gone unabated and has diminished other prominent sea star species from California to Alaska. Harvell and her colleagues are in discussions with the National Marine Fisheries Service to list the sunflower sea star as a “species of concern.”

Cornell researchers on the paper include Morgan E. Eisenlord, doctoral candidate in ecology and evolutionary biology, and Reyn Yoshioka ’14. The paper’s other researchers include lead author Diego Montecino-Latorre, University of California, Davis; senior author Joseph Gaydos, the SeaDoc Society; Karen C. Drayer Wildlife Health Center; Margaret Turner, Northeastern University; and Chirsty Pattengill-Semmens and Janna Nichols, Reef Environmental Education Foundation.

Funding for this research included a donation from Mrs. Vickie Bailey’s sixth-grade class (2013-14) at the Carl Stuart Middle School in Conway, Arkansas. Upon learning about the sea star wasting disease, the children created handmade cards about starfish and sold them for $1.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe