Students re-create music, vibe from jazz's earliest days

By Daniel Aloi

On Feb. 26, 1917, five young men from New Orleans stepped into the Victor Talking Machine Co.’s 12th-floor office on West 38th Street in New York City and inadvertently made history.

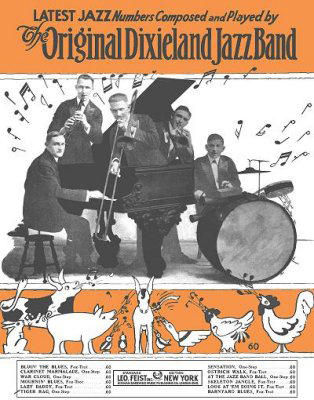

The recording session produced what would become heralded as the first jazz record, released on March 7 that year: “Livery Stable Blues” backed with “Dixieland Jass Band One-Step.”

A century to the day from that historic session, five student musicians, calling themselves The Original Cornell Syncopators, will recreate the recording session by The Original Dixieland Jass Band (ODJB), Sunday, Feb. 26, at 8 p.m. in Barnes Hall Auditorium. The event is free and open to the public. It also features the ODJB’s 1917 live repertoire, in a period-piece performance set at New York’s famed Reisenweber’s Café, featuring the Crazeology dance troupe and narrated by jazz veteran Joe Salzano.

The project is the brainchild of cornet player Colin Hancock ’19, an urban and regional studies major in the College of Architecture, Art and Planning who did much of the research.

“I’m really interested in the earliest forms of jazz, and where jazz went from there, and the next steps it took,” Hancock said. “It started in New Orleans, and in the second decade of the 20th century, it went north to New York, and Chicago, and west to San Francisco. The Original Dixieland Jass Band was maybe the second or third band to go north.”

The ODJB’s musical talents and stage antics led to stardom on record, film and in vaudeville, thanks in part to the Victor Co.’s nationwide distribution and innovative advertising. In 1917 they were exemplars of a new style that caught on fast; W.C. Handy would record “Livery Stable Blues” later that same year.

Hancock initiated a similar project while he was in high school in Texas, on Buddy Bolden, “who’s often regarded as one of the first jazz musicians ever,” he said. “There are no recordings, so the project was focused on trying to use firsthand accounts and the people who worked with him later on … to get the most accurate interpretation of the sound.”

Last fall, Paul Merrill, the Gussman Director of Jazz Ensembles, helped recruit student musicians for Hancock’s new project and the Syncopators were born.

“When I got to Cornell there was no group here doing that kind of jazz, and I wanted to do this especially because Cornell is a place where you can research things that are very specific or go in a direction to take it where you want to, and you get a lot of freedom to do that,” Hancock said. “And I met musicians, students, that are just as driven and just as interested in it and that really helped too.”

Pianist Amit Mizrahi ’19, a computer science major, said: “The first time I met Colin, in a dining hall over lunch, I could immediately sense the passion and deep respect he had for early jazz. He was very infectious.”

Drummer Noah Li ’19, an information science major, was taking private lessons in jazz drumming “as a way to expand my musical horizons. … Prior to this combo, the music I was playing was primarily punk rock. Paul approached me and thought I would be the perfect fit for this. I said, ‘Really? An early jazz combo?’”

Li’s kit includes a vintage Ludwig maple bass drum – a facsimile of what the ODJB’s Antonio Sbarbaro used. Merrill found the drum in a dumpster some years ago.

“Colin made playing this music so easy,” Li said. “He literally transcribed everything note by note. He gave me something to work off of.”

The combo also features music major Hannah Krall ’18 on clarinet and saxophones; and trombonist Rishi Verma ’19, an operations research and information engineering major. Salzano, a member of the music faculty, is credited as the Syncopators’ coach; he helped them to interact and mesh in rehearsal. Hancock also approached expert jazz historians, writers and musicians Dan Levinson, Hal Smith and David Sager, who served as mentors.

The Syncopators project, with its goal of preservation and performance of early jazz and illuminating the art form and its practitioners, is going a long way toward filling pre-Big Band era gaps in Cornell’s jazz program, Merrill said.

“I can say that it’s not just about the little black dots,” he said. “It’s about how music intersects with culture.”

The combo is on the cover of The Syncopated Times newsletter’s March issue, and will be featured on the “Jazz Lives” blog, Hancock said.

The project will expand from five to up to 11 players by the fall. Hancock wants to take on jazz’s development from 1919 to the early 1930s, focusing on early Duke Ellington and Harlem jazz, regional (“territory”) bands, and “when the solo became a big part of jazz,” he said.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe