Asteroid that killed dinosaurs may have sped up bird evolution

By Pat Leonard

Human activities could trigger an altered pattern of evolution similar to what occurred 66 million years ago, when a giant asteroid wiped out the dinosaurs, leaving birds as their only descendants.

Cornell ecology and evolutionary biology doctoral student Jacob Berv and Daniel Field, an evolutionary paleobiologist at the University of Bath, England, came to this conclusion after studying the ancient genetic evolution of birds. The researchers say knowing more about the effects of mass extinction on early bird life may reveal patterns for what lies ahead in the Anthropocene – the age dominated by humans.

“To understand the role of mass extinctions in shaping patterns of biodiversity, we’re studying how modern birds arose and diversified following the asteroid impact that marks the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary, also called the K-Pg event,” Berv said.

In a new study published July 13 in Systematic Biology, Berv and Field consider whether the K-Pg mass extinction led to a temporary acceleration in the rate of genetic evolution among its avian survivors.

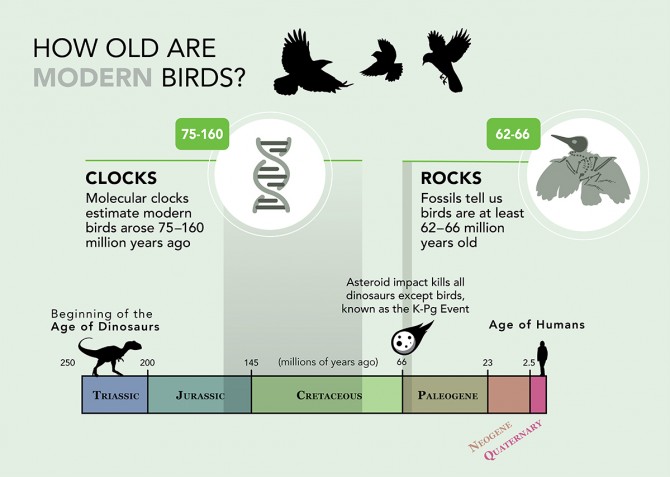

There’s often a huge discrepancy between age estimates obtained from the fossil record and estimates generated by molecular clocks, which use the rate at which DNA sequences change to estimate how evolutionary divergences between species occurred.

“The oldest fossils we know of that can be assigned to the modern bird group are scarcely older than the K-Pg boundary itself at around 66 million years,” Field said. “Molecular clocks tend to place the origination of modern birds many tens of millions of years earlier than that, well before the asteroid impact. Depending on the analysis, this discrepancy can be up to almost 100 million years – far too long to be explained by undiscovered fossils.”

Molecular clocks may overestimate ages in the avian family tree because they often assume a relatively steady rate of genetic evolution. However, if the K-Pg extinction caused avian molecular clocks to temporarily speed up, Berv and Field said this could explain at least some of the mismatch between age estimates.

The authors examined an extensive avian family tree and noticed a clear link between body size and rates of genetic evolution: Small birds evolve much faster than large ones. Using statistical modeling techniques to overcome the sparse avian fossil record, Berv and Field found avian lineages surviving the mass extinction may have been about 80 percent smaller than their pre-K-Pg counterparts. Size reductions after mass extinctions have occurred in many groups of organisms, a phenomenon dubbed the “Lilliput Effect” by paleontologists.

Berv and Field say the existing evidence is consistent with an avian Lilliput Effect across the K-Pg mass extinction.

One hypothesis is that smaller birds tend to have a faster metabolism, which generates more frequent mutations in the DNA as compared to a molecular clock that assumes a slower, steady rate of mutations over time. The exact process is still not understood, but the pattern is there, Berv said.

“The bottom line is that, by speeding up avian genetic evolution, the K-Pg mass extinction may have substantially altered the rate of the avian molecular clock,” Field said. “Similar processes may have influenced the evolution of many groups across this extinction event, like plants, mammals and other forms of life.”

The study means that the speedier rate of genetic evolution may have helped stimulate an explosion of avian diversity soon after the K-Pg extinction event.

The authors suggest human activity may be driving a similar Lilliput Effect in the modern world, as more and more large animals go extinct because of hunting and habitat destruction.

“We are currently eliminating the largest animals, just like the asteroid did. Many really big birds – the Dodo, elephant bird and the moa, for example – have already gone extinct because of human activities,” Berv said. “Right now, the planet’s large animals are being decimated – the big cats, elephants, rhinos and whales. We need to start thinking about conservation not just in terms of functional biodiversity loss, but about how our actions will affect the future of evolution itself.”

Pat Leonard is a staff writer at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe