Judy Hart’s fight for women’s rights – and a park

By Kathy Hovis

Judy Hart ’63 will never forget the day she walked into Clara Dickson Hall, late to her first meeting with 200 other freshmen girls, whose “makeup matched their knee socks.”

“I thought, ‘What did I do to myself. I am not in the same league as these girls,’” she said during a recent visit to campus. That first day of her freshman year, clad in bobby socks, she had flown, taken a bus and called a cab in Ithaca to make it to campus from her hometown of Mission Hills, Kansas. “I realized I needed to learn a whole lot in a hurry or I wasn’t going to make it around here,” she said.

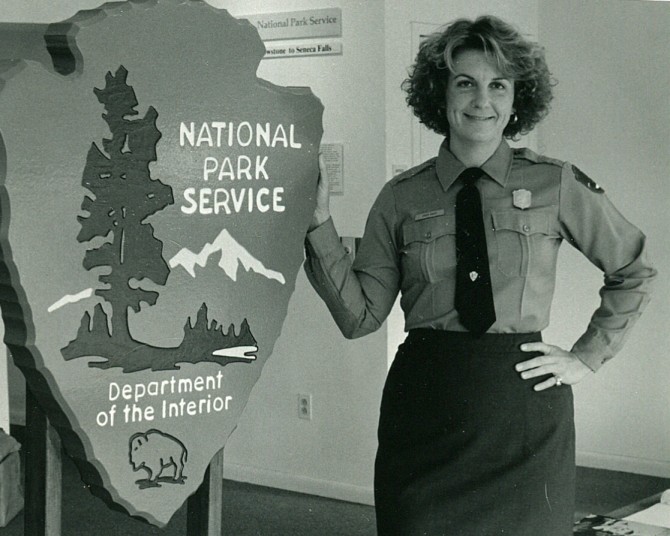

That experience, and many others at Cornell, taught Hart some of the listening, negotiating and leadership skills she would need as she worked as a relocation specialist for urban redevelopment projects in Massachusetts, as a legislative specialist with the National Park Service and as founding superintendent of both the Women’s Rights National Historical Park in Seneca Falls, New York, and the Rosie the Riveter World War II Home Front National Historical Park in Richmond, California.

Hart returned to Ithaca in September to spend a few days with friends on campus and to attend the National Women’s Hall of Fame induction ceremony in Seneca Falls.

“That first year at Cornell was very hard. I had to use every skill I had and develop a whole bunch of new ones,” Hart said. “But I realized if I can do this, I can do anything. It gave me an enormous amount of confidence for the rest of my life.”

Along with the self-awareness she gained, Hart credits Cornell with teaching her “how to write, how to speak and how to come up with an interesting thought and then express it.”

Founding the park in Seneca Falls required all these skills, Hart said.

She’s currently in discussions with Cornell University Press about a book on the founding of the park, a process that began in 1978, four years before it actually opened in 1982. If it comes to fruition, the book will be a part of Three Hills, a trade imprint of Cornell Press dedicated to the history, culture, policy and politics of New York state and the Northeast.

Hart also is conducting interviews for an oral history project at Virginia Commonwealth University.

When Hart worked for the National Park Service as a legislative specialist in the late 1970s, the agency was tasked with coming up with a list of 12 potential new parks, one for each month.

“I looked at the index of national parks and noticed an asterisk at the bottom of the page. ‘*African-American history is interpreted in all of the parks,’ it said. I knew that wasn’t true. But women’s history didn’t even get an asterisk,” she said.

She and another staff member hunted for the best location for a women’s history park. The story from there is one of listening and lobbying – with residents and officials of Seneca Falls, and with officials and lawmakers in Washington, D.C.

“I am always trying to stand in the brain of the person I’m talking to. Learning how to listen and really hear someone else is a mark of deep respect,” she said. “And if I am describing or explaining something and if they don’t understand me, it’s my fault, not theirs.”

When she faced opposition or a barrier that seemed insurmountable, Hart said she would think of time she spent on rivers – “If one pathway is blocked, the water always finds another way to make it through” – or her time spent on sailboats. “If someone was coming after me with a strong argument, I would think of lowering my sails. Sometimes there’s no point in arguing,” she said.

She also learned the value of persistence and grew more comfortable taking risks. Even after the park won approval from Congress after a bitter battle, it was given only $5,000 to get started. Hart decided she would have to move to Seneca Falls and become founding director if she wanted to keep it alive.

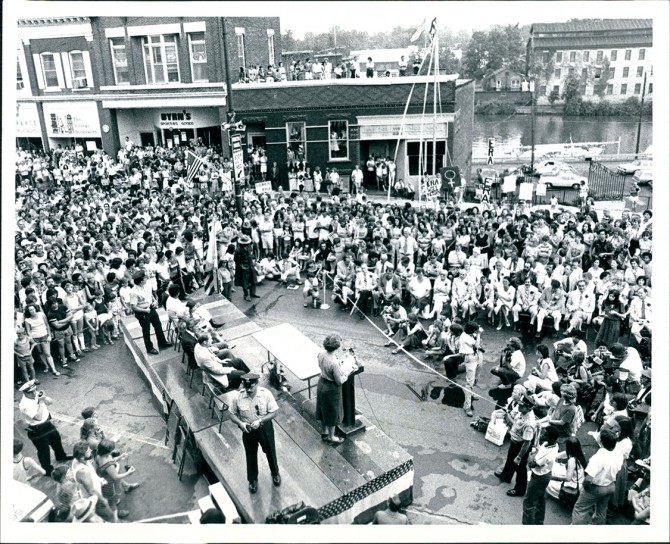

She also needed some star power for the park’s opening ceremonies, as she was worried that James Watt, President Ronald Reagan’s Secretary of the Department of the Interior, who had vowed to save money by closing down some national parks, would shutter Seneca Falls before it could even get going.

She traveled to New York City, where she successfully inspired Alan Alda, then a star of the hit TV show “M.A.S.H.,” to cut the ribbon at the opening ceremony. Alda had previously donated $11,000 to the nonprofit Stanton Foundation to purchase the Elizabeth Cady Stanton home.

When the park finally opened, Hart said she was proud to lead the first “idea park” developed by the National Park Service – one not focused on a natural area or historic buildings. Subsequent “idea” parks now include one about the Underground Railroad, one commemorating Japanese internment camps, and the Rosie the Riveter Park, which commemorates the nation’s homefront efforts during World War II.

In January, Hart visited Seneca Falls for the Women’s March, which brought 11,000 people to town. “My heart was so full I thought it would burst,” she said.

“I want women to understand that there are forces against them, and they’re real,” she said of her efforts with the Women’s Rights Park. “They can choose to live with them, react to them or fight against them, but they need to know about them.”

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe