Expert testifies on deadly deer disease to House committee

By Melanie Greaver Cordova

After a brush with chronic wasting disease in two captive deer herds in 2005, New York became the only state to successfully prevent the disease’s further spread within its borders. Other states haven’t been as fortunate: Pennsylvania, Ohio, Texas and many others are seeing this deadly disease with increasing frequency.

Krysten Schuler, wildlife disease ecologist at Cornell’s College of Veterinary Medicine, gave expert testimony and offered recommendations on the subject at a June 25 subcommittee meeting of the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Natural Resources.

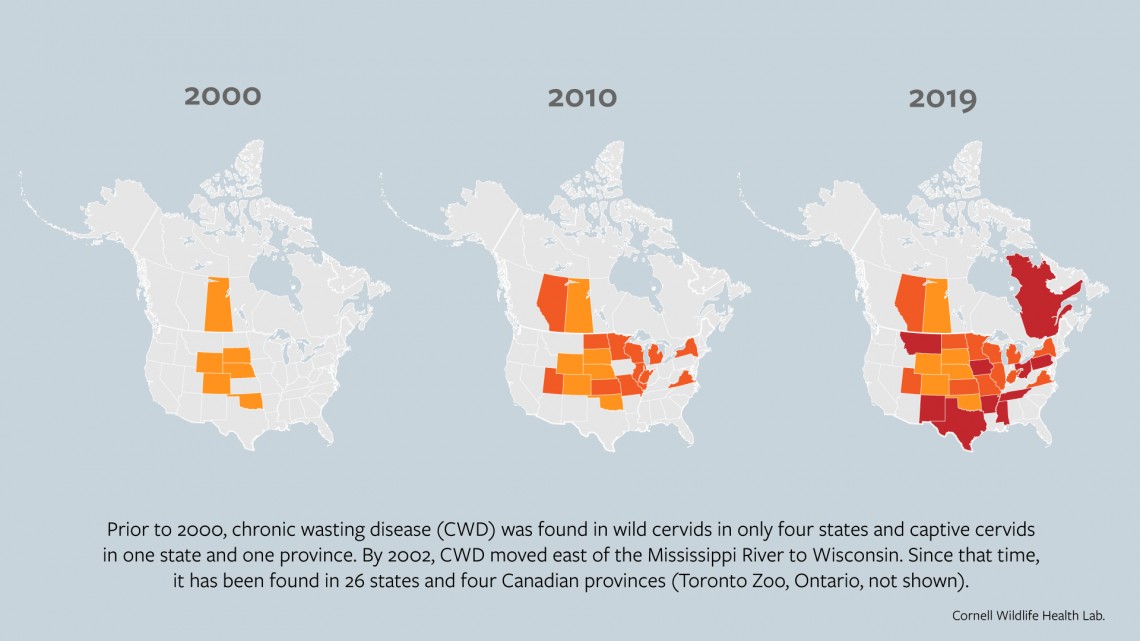

“Chronic wasting disease is the most serious threat facing wild deer and elk populations in North America today,” said Schuler, who has been studying the disease since 2002. In that time, she has seen it spread to 26 states, four Canadian provinces and four countries outside of North America: Finland, Norway, South Korea and Sweden.

“Its presence in wild animals makes it unique and exceedingly difficult to study,” Schuler said.

Chronic wasting disease (CWD) was detected in captive cervid herds in 1967 and then in wild North American cervids in 1978. The cervid family comprises members of the deer family, including reindeer and elk.

This highly contagious disease degrades the animal’s neurological system, leaving holes in the brain. Animals may be infected for a year or more before displaying symptoms, which include losing fear of people, drooling, weight loss, thirst and poor coordination. It is fatal in all cases; there are no vaccines, antibiotics, cures or treatments. Infected animals are also more likely to be killed by a predator, hunter or vehicle.

Nearly impossible to eradicate

CWD is in the family of universally fatal diseases known as transmissible spongiform encephalopathies, caused by a misfolded protein called a prion, Schuler said to the committee. Prions are resilient pathogens resistant to heat and harsh chemicals. They transmit efficiently from animal to animal or through contaminated environments. When an infected animal’s urine or blood contaminate the ground, these prions bind to soil particles and remain in the environment for up to 16 years.

Prions can also bind to plant tissues; alfalfa, wheat, corn and tomatoes are all crops that have tested positive. This may be the root of exposure for wildlife, domestic animals and humans, Schuler said.

Although there are no known cases of CWD in people, there is concern that the prions could adapt to new hosts and someday infect humans, just as the prion culprit of mad cow disease did in the United Kingdom in the 1990s.

“It is the similarity between CWD and bovine encephalopathy, or mad cow disease, that is most concerning,” Schuler said. “Over 4.5 million cows were killed in the United Kingdom, and 231 people died after eating infected beef.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have therefore issued recommendations that people not consume CWD-positive venison, and that anyone hunting in a CWD-positive area have their animal tested before consumption.

“Once CWD becomes established in a population, it is nearly impossible to eradicate. Therefore, it’s critical that we follow a precautionary principle in dealing with CWD and take preventative action in the face of uncertainty,” Schuler said.

Schuler and her colleagues at the New York State Wildlife Health Program have done just that for New York. She and wildlife veterinarian Dr. Elizabeth Bunting have worked together since the start of the program to spearhead training for those who come into contact with animals in the field – such as biologists, law enforcement officials and even taxidermists – to monitor for CWD as well as other diseases and conditions.

“New York has maintained an aggressive stance toward CWD and continues to serve as a model for programs in other states,” said Schuler.

Prevention, management are vital

Because the disease is present in wildlife and can contaminate the environment for long periods of time, it is unlikely that North America can eradicate CWD completely. Therefore, prevention and management are key.

“Large sections of the country have not encountered CWD yet and can take steps to keep prions out,” said Schuler, noting that the biggest hurdles to doing so are the natural movement of live infected cervids and the transportation of their parts and products by hunters and others.

In her testimony to the committee, and in answer to their questions, Schuler offered recommendations for combating the spread of CWD, including:

- sustained fiscal support for state and federal wildlife agencies, as well as veterinary and wildlife diagnostic labs;

- funding for research that could lead to breakthroughs in treatment and prevention; and

- improved support from stakeholders to their elected officials to raise awareness of the disease.

“At its core, CWD erodes our public trust resources,” said Schuler. “Any meaningful strategies to combat CWD will require long-term approaches with sustained state and federal efforts.”

Schuler’s written testimony is available online, and the House Natural Resources Committee Democrats livestreamed the proceedings on YouTube.

Melanie Greaver Cordova is a staff writer with the College of Veterinary Medicine.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe