Study reframes the history of LGBT mental health care

By Kate Blackwood

New research reveals that community-based clinics and clinicians play an essential role in reshaping both mental health care for LGBT people and broader attitudes about sexuality and gender.

Stephen Vider, assistant professor of history in the College of Arts and Sciences, is a co-author with David S. Byers, assistant professor at Bryn Mawr College Graduate School of Social Work and Social Research, of “Clinical Activism in Community-based Practice: The Case of LGBT Affirmative Care at the Eromin Center, Philadelphia, 1973–1984,” which was published Nov. 9 in American Psychologist.

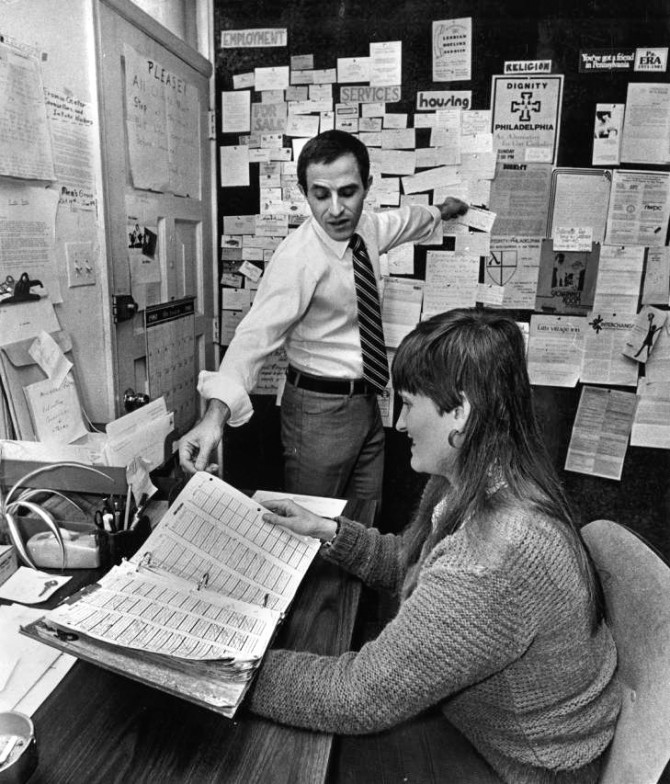

Their paper uncovers the story of the Eromin Center, one of the first LGBT counseling centers in the United States, which was open in Philadelphia from 1973 to 1984. Eromin was a portmanteau for “erotic minorities.”

Historically, LGBT people struggled to find mental health care that didn’t treat divergence from sexual and gender norms as a mark of psychopathology. The authors show how Eromin’s proactive stance not only provided support for people who needed mental health care but also advanced a new model of LGBT affirmative clinical practice.

They describe Eromin’s approach as an example of what they call “clinical activism.” Without pre-existing models or research to draw upon, Eromin clinicians improvised new therapeutic approaches, guided by their own ethics and experiences.

This improvisational and community-responsive approach to care, the authors argue, was used by many early LGBT counseling centers in the United States, in spite of national leadership and mental health policy that was slower to change.

“Most histories of LGBT mental health point to the removal of homosexuality from the ‘Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders’ in late 1973 by the American Psychiatric Association as the crucial turning point in LGBT depathologization,” said Vider. “Our research shows, however, the critical role of clinicians working in developing models of affirmative LGBT counseling.”

Eromin, in fact, was founded six months before the APA decision.

Their paper, written with Amelia Smith, a social worker at the Mazzoni Center in Philadelphia, is part of an oral history and archival research project that Byers and Vider have been leading since 2015. The oral histories will be archived in Cornell University Library’s Rare and Manuscript Collections as part of its Human Sexuality Collection.

The Eromin Center, the authors wrote, “framed the major problem facing LGBT people not as inherent psychopathology but as marginalization.” One goal was to counteract the stigma and discrimination; another was to help clients achieve self-acceptance and develop personal strengths. Most of Eromin’s counselors were gay or lesbian, and gave treatment rooted in their own experiences.

By 1977, more than 1,000 people had received care. Eromin also pioneered counseling and support services for transgender clients, and by the 1980s, was working to develop more programming for LGBT people of color.

The center closed in 1984, but the impact it and other LGBT clinics have had on counseling in the United States has been crucial, Vider said.

“The APA may have depathologized same-sex desire on paper,” he said, “but it was clinicians in programs like Eromin who ultimately made self-acceptance possible.”

Even after the APA decision, Vider said, many clinicians continued to treat same-sex sexuality and transgender identity as forms of mental illness that needed to be “cured.” Eromin provided and modeled a critical alternative.

Byers said there is still need for change.

“Today, many clinical training programs, social service agencies and professional organizations work to some degree to affirm LGBT people and other marginalized identities, experiences and expressions,” he said. “The care remains very uneven, though.”

It can be especially difficult, he said, to access thoughtful and individualized mental health care related to transgender identities and experiences. Another challenge is a still-active network of clinicians who claim they can change a client’s sexual orientation or gender expression.

Byers stressed the need for clinicians in the field to take a critical and anti-oppressive stance in their work, and for graduate programs and medical schools to empower new clinicians to be responsive to local needs. Byers said, “Today, social workers, psychiatrists and psychologists often fail to listen with an ear to the political aspects of their practice. We are not trained to work together with our clients or to be creative in the collaboration. However, clinicians today absolutely need to pursue new forms of clinical activism. The status quo in community-based mental health care is often ethically unacceptable.”

At the same time, Byers said there are many clinicians engaging in clinical activism throughout the country right now, though with little recognition.

“Clinicians face systemic challenges,” he said, “and lack of support while working with people with marginalized sexual orientations and gender identities; with individuals experiencing poverty, racism, misogyny or trauma; and in response to anti-immigrant and anti-refugee violence.”

“One lesson of the Eromin Center is that change at the level of policy and guidelines is often not enough,” said Vider. “Real and lasting change has to start within communities.”

Vider is director of the Cornell Public History Initiative. In the spring, he will teach a lecture course on the history of mental illness and a seminar, Making Public Queer History.

Byers will be a postdoctoral associate at the Bronfenbrenner Center for Translational Research, beginning in fall 2020.

Kate Blackwood is a writer for the College of Arts and Sciences.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe