Nicholas Klein, assistant professor of city and regional planning, next to an improperly parked car in Collegetown.

Study explores micromobility, improper parking in 5 cities

By Daniel Aloi

“Scooter clutter” has been a concern amplified by media reports in urban areas where micromobility has entered the landscape, with large numbers of dockless scooters and shared e-bikes on city streets and sidewalks. But a recent study finds that motor vehicles are still the main offender by far when it comes to blocking access by other travelers.

Research co-authored by Nicholas Klein, assistant professor of city and regional planning in the College of Architecture, Art and Planning, offers data on the impacts of scooters and bikeshare vehicles in five American cities.

The research is translatable and replicable, to help inform cities’ efforts in reimagining public streets and sidewalks. Some cities are considering new parking regulations and seeking other planning and policy solutions for these shared scooters and bikes, which have been introduced to more than 100 cities since 2018.

“Cities around the country are struggling in coming up with new regulations and thinking about what they should do about these new forms of technology,” Klein said. “And they’re doing that in the absence of any real data, and consistent data, about how these things are parked.”

The paper, published March 3 in Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, investigated scooter, bike and car parking behavior in Austin, Texas; Portland, Oregon; San Francisco and Santa Monica, California; and Washington, D.C. The research was led by Anne Brown of the University of Oregon School of Planning, Public Policy and Management.

Researchers collected 3,666 observations of e-scooters, bikes, motor vehicles and “sidewalk objects” such as sandwich boards. Research assistants recorded parking behavior on both sides of a busy commercial corridor for three days, eight hours each day. They observed parked cars, scooters and bicycles, as well as sidewalk furniture including advertising, construction materials and sidewalk-mounted elevator or stair-access doors.

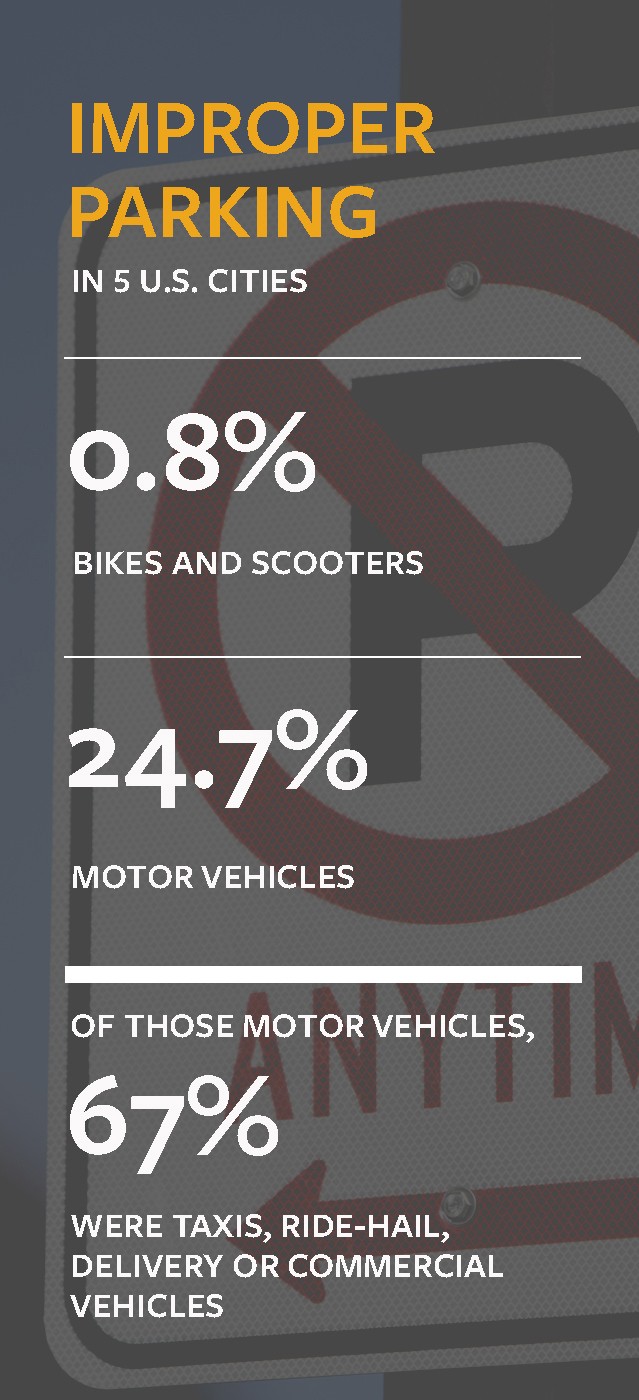

The study found that parking noncompliance rates across the five cities were far higher for motor vehicles (24.7% of 2,631 motor vehicles observed) than for micromobility vehicles (0.8% of 865 scooter and bike observations).

Food delivery and ride-hailing vehicles accounted for a disproportionate number of improper parking incidents impeding access or mobility for other travelers, Klein said. Most of these violations occurred while dropping off or picking up people or food, including double parking, occupying “No Parking” or restricted areas and blocking driveways.

The findings suggest that the presence of micromobility companies and other technology-enabled transportation services should motivate cities to rethink their parking policies, the researchers said. “Comprehensive policies would include tech-enabled transportation as well as motor vehicle parking more generally,” Klein said.

“One of the things we’re really excited about with this research was putting all the methods and data collection tools online – so cities and whoever else, really, can easily replicate this using the same methods,” Brown said.

“Our interests can be very different from those of a planner working for another city,” Klein said. “They might be less interested in understanding one block, and much more interested in the neighborhood effects of how this varies across a commercial district, or across a residential area. Or they might know where certain issues are really prevalent, and use this to understand the broader impacts.”

In addition to Klein, co-investigators on the collaborative research included Calvin Thigpen, policy researcher for Lime, an electric scooter and bike rental company based in San Francisco; and Nicholas Williams, deputy chief of staff of Denver Public Works, who is charged with policy, legislative affairs and special initiatives for the city and county of Denver, Colorado.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe