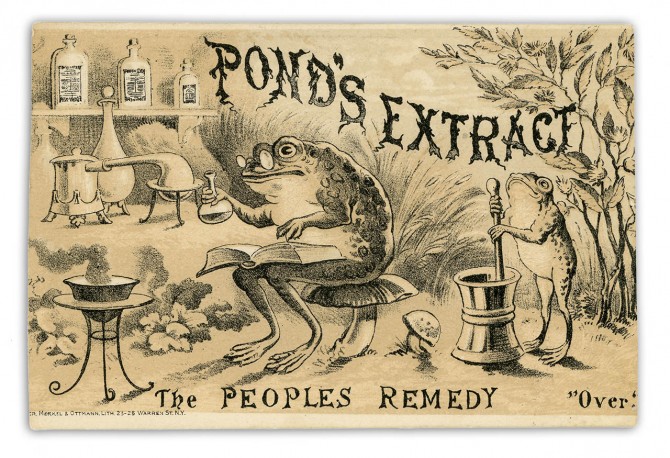

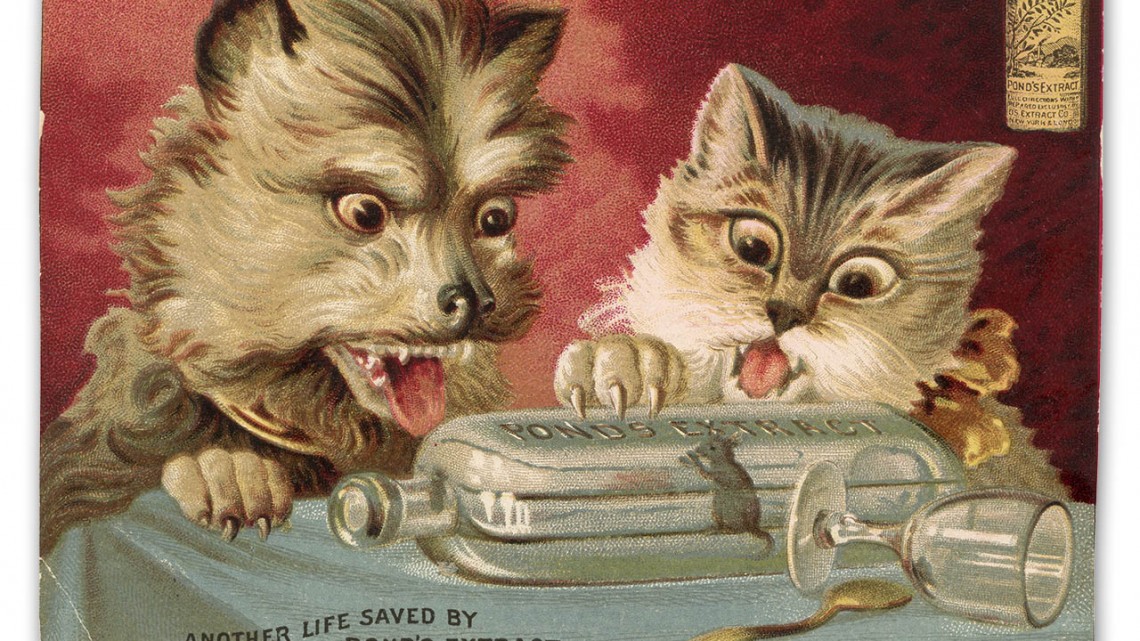

Pond's Extract, from Pond's Extract Co. (New York City)

Collection offers glimpse at era of patent medicine ads

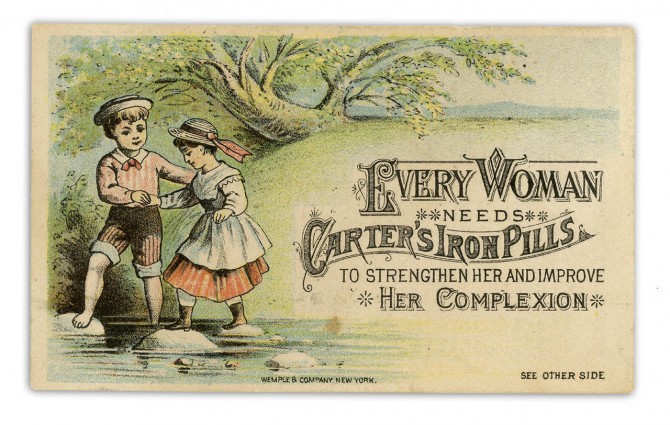

Have you been hoping for a miracle cure-all to improve your complexion, or to get rid of those pesky kidney stones, or perhaps to even prevent balding? If so, you’re not alone! In the 1800s, Americans were targeted with advertisements for what were often considered “cure-all” medicines, presented in colorful trade cards meant to directly connect patent medicine manufacturers to the consumer public.

A collection of 197 medical trade cards advertising a variety of products and cures produced in the latter half of the 19th century is preserved and available for research in the Medical Center Archives at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City.

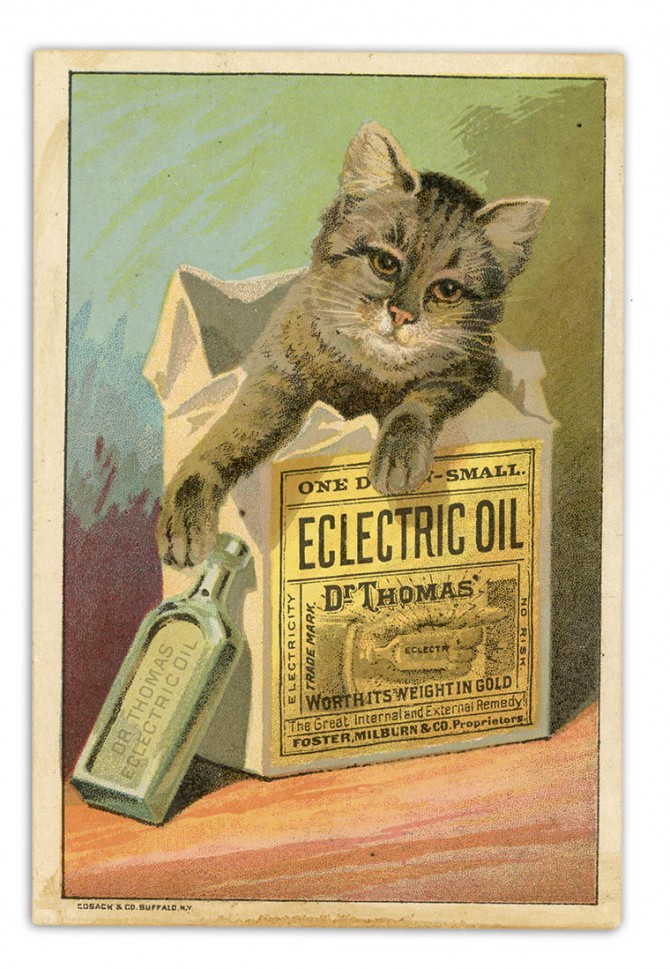

Patent medicines, also known as proprietary medicines, were mass-produced remedies created from homemade formulas that rose in popularity in the 19th century. Despite their often limited or non-existent medical efficacy, they were marketed through trade cards boasting cheaper cures for colds, cholera, tuberculosis, whooping cough, constipation, asthma, malaria, sore throats, eczema, nervousness and what was then referred to as “female weakness,” among many other ailments.

Patent medicine manufacturers were unregulated at the time and not required to list the active ingredients of their products, some of which contained high volumes of alcohol mixed with ingredients such as heroin, cocaine, morphine, marijuana and mercury.

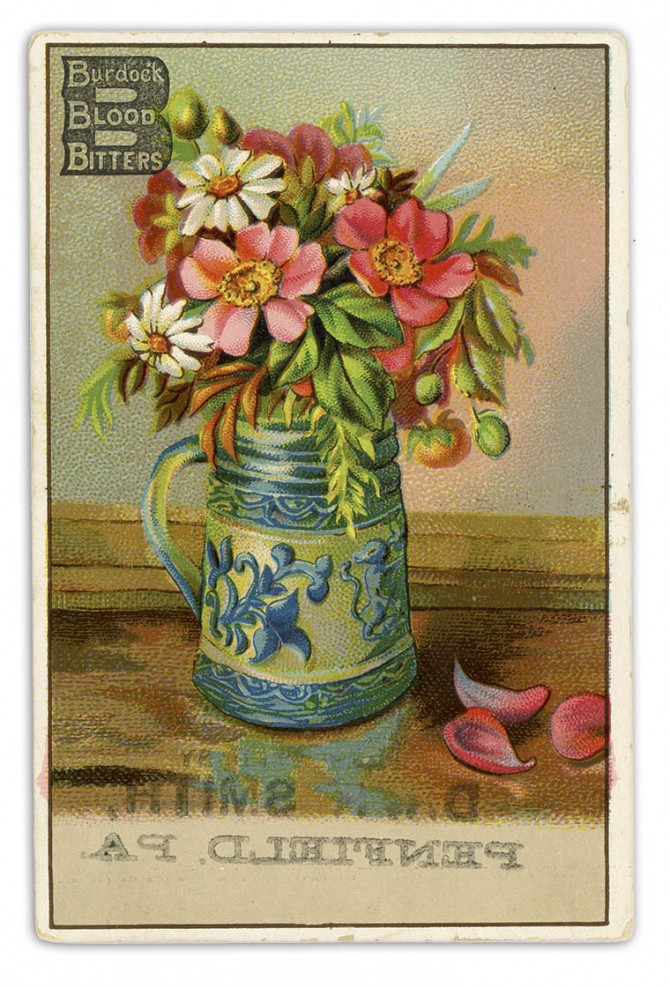

Unlike traditional newspaper advertisements, the trade cards of this era were an innovation due to their use of vibrant colors, the unrestricted variety of products promoted and the ease with which they were circulated to the public. Trade cards also increased in popularity as the hobby of scrapbooking began to grow in the United States. Advertisers took advantage of this new trend by creating distinctive, eye-catching designs, which were mass-produced thanks to the development of lithography.

The imagery they employed was meant to appeal to contemporary consumer tastes, with illustrations featuring flower bouquets, rosy-cheeked children, happy families and animals. Some trade cards also depicted and perpetuated misogynistic sentiment, as well as negative racial and ethnic stereotypes.

– Rebecca Snyder and Nicole Milano

This story originally appeared in the online-only spring 2020 issue of Ezra magazine.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe