Food science professor’s ‘instant ice cream’ gains patent

By Blaine Friedlander

One moment, you have a bowl of creamy chocolate liquid. Then, in an instant, it’s ice cream.

Forget hocus-pocus: This is physics and engineering.

After a five-year application process, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office awarded Patent No. 10,624,363 B on April 21 to Syed Rizvi, professor of food science engineering, and Michael E. Wagner, Ph.D. ’15. And just like that, the world got a little sweeter.

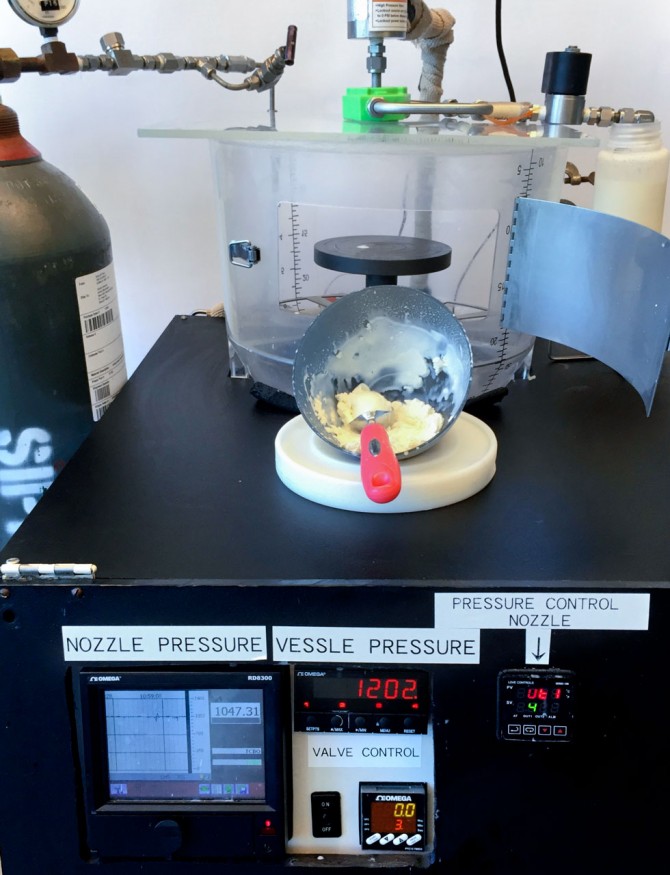

With Rizvi and Wagner’s newly patented process – where pressurized carbon dioxide does all the work – anyone can make any ice cream at any time.

“Of course, you’ll need the liquid ice cream mix,” Rizvi said. “The mix can be made commercially, locally or you can make it at home. It’s very simple, and this machine converts the mix into a scoop of ice cream in about three seconds.”

In the traditional method of making ice cream, the dairy-based mix flows through a heat-exchanging barrel, where ice crystals form and get scraped by blades.

With this new method, highly pressurized carbon dioxide passes over a nozzle that, in turn, creates a vacuum to draw in the liquid ice cream. When carbon dioxide goes from a high pressure to a lower pressure, it cools the mixture to about minus 70 degrees C – freezing the mixture into ice cream, which jets out of another nozzle into a bowl, ready to eat.

Instant ice cream can be served right on the spot, all without the challenges of commercial transportation “cold chains,” in which the product must be frozen and maintained at minus 20 degrees Celsius. To guard against failing spots in the cold-temperature transportation chain, commercial ice cream makers add stabilizers and emulsifiers.

“Consumers today want a clean product,” Rizvi said. “They don’t want undesirable ingredients thrown into it.”

What’s more, Rizvi said, the cold chain requires a lot of energy. But if you could make ice cream without stabilization ingredients, commercial entities could avoid the cold chain altogether.

The device can take any liquid and give it frozen features. “You can make a slushy out of soft drinks,” he said, while noting that the new process is suited for on-demand and point-of-use applications like vending machines, parlors and home use. “You can convert water into carbonated ice instantly, too. Any liquid drink that can be partially frozen can be used.”

Cornell’s Center for Technology Licensing is currently exploring licensing opportunities.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe