Elizabeth Rawlings, left, wife of President Emeritus Hunter Rawlings, photographs Rosa Rhodes, Frank Rhodes and professor Robin Davisson during Charter Day Weekend in 2015.

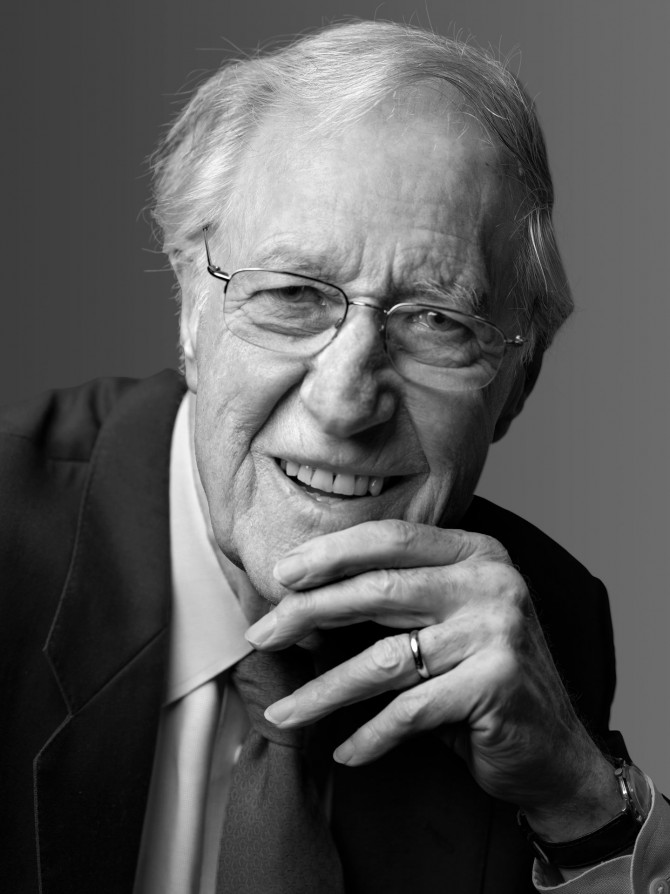

Frank H.T. Rhodes: Essential, eloquent and beloved

By Ezra Cornell

He was an influential scholar, a dazzling orator and an inspiring leader. His transformative 18 years as Cornell’s ninth president were followed by almost another quarter century of his continuing wisdom, enthusiastic national advocacy for higher education and research institutions, ongoing scholarship, and indefatigable championing of the university.

Our community lost one of its brightest and longest-lasting lights when Frank H.T. Rhodes died Feb. 3 at the age of 93. I had the privilege of knowing him from the very beginning of his presidency and worked with him in my role as a trustee and in friendship for more than four decades.

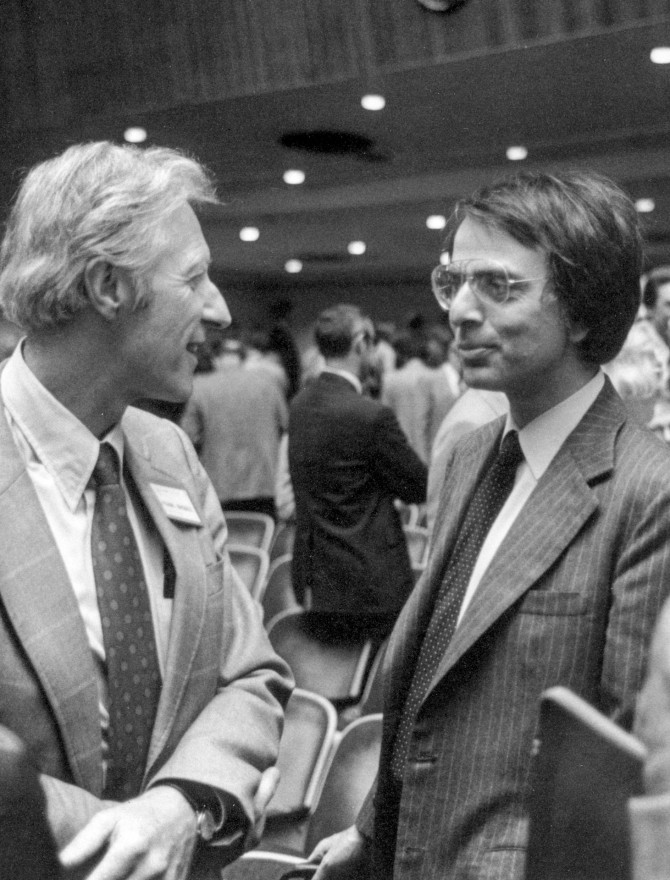

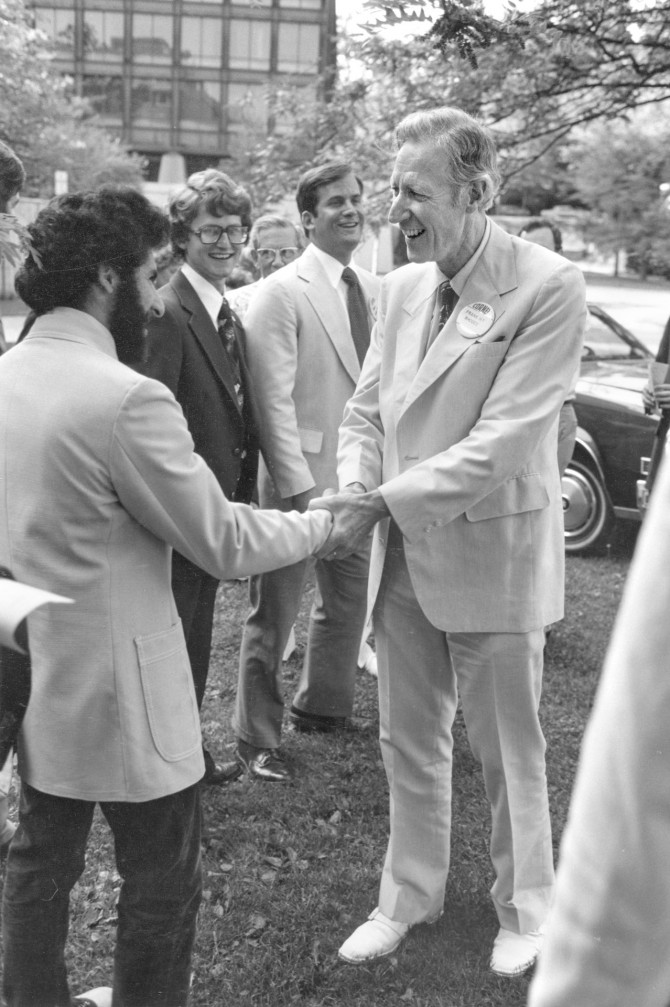

I remember my first impression of him when I met him at a trustee meeting in New York City: He was impressively tall, dressed in a blue suit – with an appropriately chosen red tie – and was all smiles. But what struck me immediately was his eloquence and graciousness, his optimism and energy. He was incredibly smart and could converse with anyone on any topic.

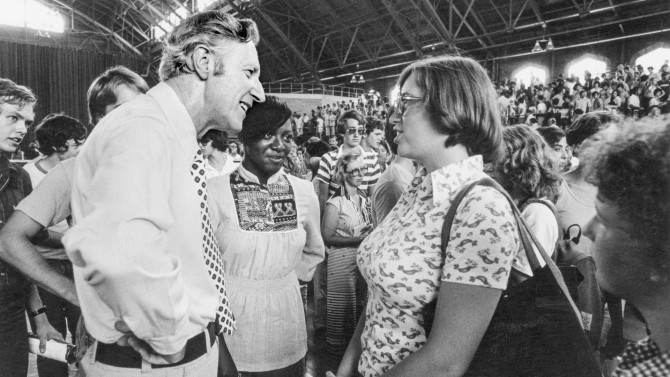

Frank’s inaugural address, delivered Nov. 10, 1977, to more than 6,000 people in Barton Hall, was fabulous. In it, he revisited professor and university historian Morris Bishop’s famed 1939 essay “Perhaps Cornell”– in which Bishop criticized a newspaper writer who had claimed that only a handful of universities in the U.S. were truly places of distinction and “typical American colleges,” naming “Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and perhaps Cornell.”

Bishop celebrated the fact that Cornell had no “fixed and sure classification” and claimed the university’s uniqueness as an asset, remarking that someday, someone seeking “the essentially American college will specify Cornell University. And perhaps Harvard, Yale and Princeton.”

Frank, too, embraced Cornell’s distinctive role and character while noting that the “perhaps Cornell” phrase haunted him, as it did Bishop – but not “as an uninformed and pompous judgment of our past, but as challenge and hope for our future.”

In that inaugural address, Frank stressed four “reaffirmations” necessary to secure a healthy future for the university: the power of reason; the strength of community that is Cornell; the priority of research and teaching; and the importance of the wider partnership beyond the campus. For each of these reaffirmations, he said, “perhaps Cornell” can lead the way.

“The research university is the great reservoir on which the fulfillment of all our hopes and larger social aspirations must draw,” he said. “Knowledge is the base of the pyramid of progress.” He noted that major research universities, working together, could “represent the beginning of a new hope for humankind.”

“So this is a time for renewal. It is a time for hope. It is a time of new commitment,” he concluded, officially accepting his role as president, adding that he shared in the hope that “Cornell has a future destiny far greater even than her great past.”

Prior to Frank’s arrival, the campus had been recovering from the troubles of the late ’60s and early ’70s. Frank’s idea of Cornell was an aspiration for the whole university and for each person. Setting the university on a new, optimistic course, he lifted our spirits and showed the way.

His imprint on Cornell was felt more and more each year, not just in the steady appearance of new buildings and facilities, but in a renewed definition of success within the university’s departments and colleges. He did a great deal to strengthen the quality of education – always stressing the central importance of the role of teaching – and was often personally involved with recruiting faculty talent. Frank was always humble, except when expressing boundless pride in having had a hand in hiring a star for the faculty.

One of my favorite moments with Frank happened in his office, around 1982. He presented me with a foot-high cast replica of the statue of Ezra Cornell, our founder and my great-great-great-grandfather, that overlooks the Arts Quad.

Frank suggested I take note of a special inscription on the heavy marble base: “To a chip off the old block.” That caused us both to burst into laughter, but the meaning was clear. Frank knew I shared his and the founder’s vision for our graduates: to be extraordinary men and women with knowledge, conviction, passion and dreams.

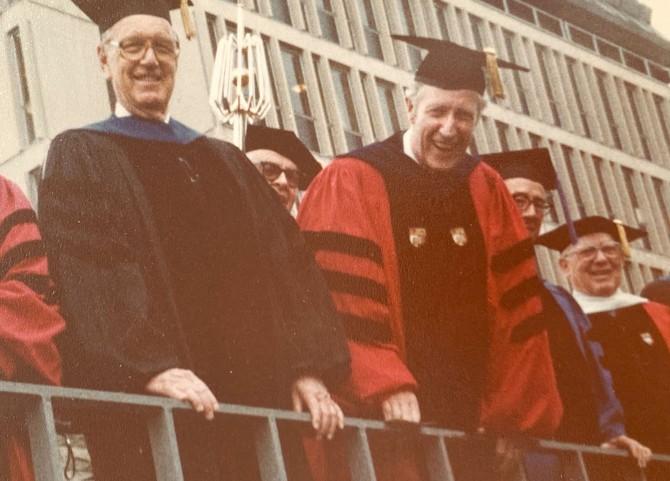

I believe I sat on the podium at every commencement ceremony during Frank’s time as president. Whether he was speaking to a group of three, or in front of 30,000 people at Schoellkopf Field, he had an ability to connect and enable each person to feel welcome and tuned into every word. Through that perfect British diction, and because he was both humble and dynamic, he made each and every address meaningful for the graduates and their families.

He ended every one of his addresses to Cornell’s thousands of graduates with the memorable Gaelic blessing: “And, until we meet again, may God hold you in the palm of his hand.”

There must be countless thousands of pictures of Frank standing happily in his red robe and regalia, posing with graduates and parents.

As many Cornellians recall, Frank had an awesome memory for names and faces, probably because he cared so much about everyone. He seemed to remember, with shared good cheer and graciousness, all the alumni he had ever met. And, just as he knew the importance of pausing in a speech, he took the time to really listen when a one-on-one conversation needed his full attention to fully connect. He made an indelible impression on this campus and around the world.

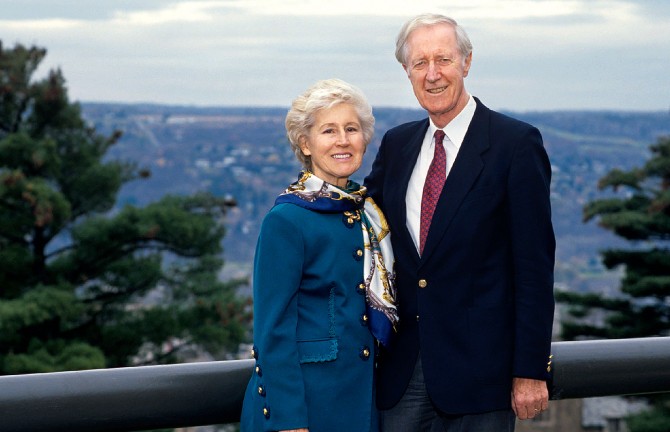

And, of course, nearly everywhere Frank went, his wife, Rosa, was there too. They were always together at university events.

Frank’s very public admiration and stated affections for her were inspiring. Rosa was truly his strong partner in marriage (for 67 years!) and in his presidency. Rosa knew almost as many Cornellians as he did, and I am sure alumni will always love her and their family, as my wife, Daphne, and I do.

Over these past couple of months, as I have been reminiscing with people who knew Frank well, so many of his wonderful qualities and characteristics have been fondly and vividly recalled. What was most apparent was his incredible intellect and the enormous breadth of his interests in the future of mankind.

This is the Frank we knew. Cornell University as an institution is forever enriched by his sage leadership, and Cornellians themselves – tens of thousands of us – benefited not only from his wisdom, intelligence and expertise, but also from his humanity.

I am proud to count myself among them.

Ezra Cornell ’70 is Cornell University’s life trustee.

This story originally appeared in the online-only spring 2020 issue of Ezra magazine.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe