As the radically altered spring semester comes to an end, faculty and students talk about the experience of teaching and learning remotely.

Six stories of six weeks of virtual learning

By Melanie Lefkowitz

Spring 2020 was a semester like no other. Over the course of a few weeks, thousands of classes – lectures and seminars, laboratory and performance courses, capstone projects and veterinary clinics – transitioned entirely online. Instructors navigated technical and logistical difficulties, as well as the shifting realities of a global pandemic. But amid the challenges, students and faculty found opportunities for innovation, connection and intellectual growth.

Here are snapshots of six courses that took creative approaches to their online formats.

Virtual reality provides a sense of place

The cardboard goggles cost around $8. Their delivery took weeks. And when the students saw each other wearing them on Zoom, they laughed.

“It’s really low-tech,” said Jennifer Birkeland, assistant professor of landscape architecture in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. “You use this cardboard viewer and stick your phone inside it, and a series of apps lets you capture virtual environments. Then the rest of us can log in and essentially look at each other’s ‘photospheres.’”

Normally, the master’s students in LA 5020, Studio Composition and Theory, would spend the semester redesigning a public plaza in Syracuse, New York. This semester they pivoted to reimagine spots near and dear to their hearts – and their homes. Virtual reality not only allowed them to see and experience each other’s projects, it helped energize students who were demoralized by the abrupt end of their time together on campus.

“It feels like were taking little field trips around the country – we’ve been to L.A., Oklahoma; I’m in Michigan, a few people are back in Ithaca,” said master’s student Monica Rourke, whose own project focuses on a stream through her property. “You have a sense of hopping around.”

The landscape architecture class, part of the first year of a three-year master’s curriculum, aims to help students understand spatial relationships through physical and digital drawing. Virtual reality, already widely used in architecture to present proposals or to experience international sites without traveling, provides a new way to help students reach their goals, Birkeland said.

“Virtual and digital environments are not necessarily superior, but at a time like this when nobody can go anywhere, it gives you a sense of place,” she said. “I’m just trying to get them to think like designers and be able to craft a narrative and build their argument, but I’m also trying to prepare them for that job interview after they graduate.”

As always, the students will present their final projects to a jury of professionals.

“Because Ithaca’s so remote, it’s often challenging to get outside critics to take two days off and get on the campus-to-campus bus,” Birkeland said. “Now, the fact that everybody’s home and everybody’s available means I can call really great designers and academics and say, ‘Hey, do you have an hour?’ and they say, ‘Of course.’ So the students are getting really awesome feedback.”

To some students, the isolation was a greater challenge than the VR. “We’ve all grown up in an age with rapidly changing technology, so I think we’re all used to incorporating new technology into our lives pretty seamlessly,” Rourke said.

The experiment sparked spirited debate about the pros and cons of digital tools, Birkeland said.

“There was a great discussion about the limits of technology, and how you might make virtual reality more sensory,” she said. “They’re starting to really see what tools are available, and how they can adapt and problem-solve. The VR has given them a little more agency. They’re inspiring each other.”

Reimagining the jazz ensemble

Lior Kreindler ’20 made a microphone stand out of a reading light clamp and yoga mats. She dangles her phone from a hanger in her closet using duct tape. Then, facing the closet, she records herself playing a trumpet track.

“Our improv skills are coming in handy now,” said Kreindler, a student in MUSIC 4615, Jazz Ensemble, where performers now meet at what they’re calling “Zoom-hearsals” and contribute music one track at a time rather than together in a room.

“I didn’t want to lose the experience of making music together,” said Paul Merrill, senior lecturer and the Herbert Gussman Director of Jazz in the College of Arts and Sciences. “I was really curious to know how musical communication would evolve during remote instruction, and what this could teach us about zero-latency performance. I trust one takeaway will be a better understanding of how traditional concepts of music-making are negotiated on the bandstand.”

The creative interplay of performing together is something the students miss desperately.

“When I have other musicians, I can tune off of them, I can get energy off of them, and I’m able to keep track of where I am by where we are inside the melody,” said bassist Stephen Chin ’21. “Without that, it kind of feels like a practice session with myself.”

Still, they’re finding unexpected benefits. Trumpeter Tharun Sankar ’20 said the virtual format gives him more time to work on technical skills. Kreindler said she’s been able to teach herself about recording and even recorded her own arrangements, including a composition she titled “Quarantine Blues.”

And Chin said the opportunity to re-record himself – rather than having to accept whatever version he played live – is helping him move away from idealized notions of how he ought to sound.

“It’s an interesting position for improvisers – you have time to consider if a contribution is of value or not. Sometimes mistakes add significance and help define perfection,” Merrill said. “If everything’s perfect, is it truly human? These are the kinds of fundamental questions that keep me up at night as we labor to reimagine the jazz ensemble virtually.”

Redesigning bioinstruments

Creating an electronic device in a laboratory is not the same as designing one online.

“All of our students needed to do a project, which is a hands-on thing,” said Mingming Wu, professor of biological and environmental engineering in CALS, who teaches BEE 4500, Bioinstrumentation. “No matter how magical we are, that’s something we really couldn’t make happen.”

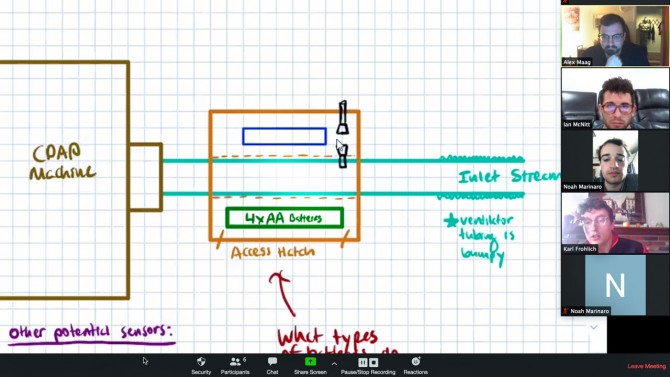

Alex Maag, a postdoctoral researcher who co-teaches BEE 4500, came up with perhaps the next best thing: online simulators allowing students to virtually wire and code Arduinos, the mini-computers that power their devices.

“They can create the circuitry, and in addition they can code, and it tells you whether it works properly or not,” Maag said. “So it essentially simulates exactly what they would have done if they’d created an Arduino unit for their project.”

Originally, Maag’s group of students planned to build robots that could use machine learning to assess whether crops were ripe by observing their colors. “Obviously, we can’t do that now,” he said. “We thought about it, but we can’t ship electrical components to one person, and have two other people working on development.”

Then he came across a universitywide call for coronavirus-related technology. Repurposing machines used to treat sleep apnea into ventilators, the students realized, would not only offer the same experience developing pressure-based sensors that they would have gotten from the robot project, it could potentially aid in the fight against COVID-19.

“I created a quick writeup for my group, and they immediately just jumped right on it,” Maag said. “They found this a very good use of their time in this current environment, and immediately started researching the best way to go about it.”

Two of the five projects in Bioinstrumentation are now coronavirus-related; another group of students is exploring the mechanics of how viral droplets spread in the air under different conditions.

“This is really an instrument course – we ask students to learn how to design and make a thing to solve a real-life problem, so my take is that they would have loved to go in the lab and see if it works,” Wu said. “It’s different than we anticipated, but it’s still fun. They’re still learning new things.”

Finding optimism in virtual rounds

When she was struggling because of her learning disability, Lili Becktell kept her spirits up by looking forward to her third year at the College of Veterinary Medicine, when she’d work directly with animals in clinical rounds.

Then, just as clinics were set to begin, veterinary students learned they’d have to leave campus and shift to virtual learning for the remainder of the semester.

“It was a crushing blow,” Becktell said. “When you spend three years in this very, very difficult curriculum, clinics is the light at the end of the tunnel. My learning disability kept me from excelling in the didactic setting, but this is the part of the curriculum where I knew I would shine.”

As students dealt with disappointment, faculty, residents, CVM leadership and support staff raced to adapt a mode of teaching that relies heavily on face-to-face interaction: standing in the same room with the animal and its owner; brainstorming ideas about the animal’s condition with peers; and learning lifelong lessons through the responsibility of caring for an animal’s health and well-being.

Using a combination of recorded lectures, detailed photographs, notes and videos from past cases, and live Zoom sessions with clinicians in the veterinary hospital, instructors have created a version of virtual rounds to prepare students as fully as possible.

“Incorporating photos and videos of clinical cases was very effective,” said Dr. Rolfe Radcliffe, senior lecturer in large animal surgery, who presented to students about the case of a foal impaled on part of a fence, injuring its thorax and abdominal cavity. “We had really good timelines and a very good documentation for that case.”

Building time for questions and comments for students into Zoom sessions helps approximate the back-and-forth of an in-person conversation, Radcliffe said. Curating past cases exposes students to a comprehensive range of large animal conditions, symptoms and treatments.

The responsiveness of her instructors helped Becktell find optimism, she said, noting that Radcliffe even commented on one of her online discussion posts.

“He said, ‘I know you’re saying that you’re struggling, but what I’m seeing is someone who clearly wants to understand and wants to work hard, and I want to do what I can to make this relevant for you,’” Becktell said.

“It has been really difficult in this virtual medium, but overall the experience has been really positive – if not from the get-go, then definitely trending that way,” she said. “I’m starting to feel hopeful again.”

Expanding in certain dimensions

Dance requires space. Space to stretch and move your limbs, to experiment with your body. Space to strut and leap and roll.

Far from the studio in the Schwartz Center for Performing Arts where they once met, students in Julie Nathanielsz’s Dance Technique I class are learning to use their surroundings differently.

“Because I can’t make assumptions anymore about dimensions, it becomes more about [their] relationship to available space, without defining what that space is,” said Nathanielsz, a visiting lecturer in the Department of Performing and Media Arts in the College of Arts and Sciences.

Some students work in tiny bedrooms. Others can’t even step outside. One spent two weeks confined to a hotel room.

“Dance looks for non-daily ways of being in relation to where you are,” Nathanielsz said. “So we have fixed ideas about the places that we’re living, and dance is a fun way to maybe expand that in certain dimensions.”

Dancing always requires trial and error, spatial awareness, creativity and flexibility, but teaching and performing dance via Zoom requires far more. Nathanielsz’s approach evolved to maximize students’ relationship to dance, to the class and to each other. Instead of demonstrating movements live, she now records sequences for students to work through independently; instead of devoting time to solo dancing, she’s prioritizing group work – because students are so isolated already.

“I expected she was just going to post videos, because I thought: How is dance going to work through Zoom – is that even possible? But she’s making it work,” said Heysil Baez ’23. “She’ll verbally explain something and then wants to see how we interpret it, which is kind of like the experimentation we’d do in class, which makes the class a little more personal.”

Nathanielsz has had to be particularly inventive in using the camera – mostly because few students’ rooms are big enough to position a camera to view them from head to foot.

“If we need to see each other all the time, that’s really limiting,” Nathanielsz said. “But if I say, listen to the video, take the cues, do what you can where you are; and then we reconvene and get to look at each other, that seems like a much more valuable use of the camera.”

With the class, Nathanielsz has also explored smaller movements.

“Condensing – drawing the limbs in,” she said. “Something that still works with a sense of radiant or strong energy, that might not be able to be used in a big spatial gesture. … I’m taking more from yoga, generating resistance inside one’s own system.”

Even limited movements, students said, are better than none at all.

“I feel a little trapped in my house, and having the class, at least for that hour and a half that we’re moving, takes the stress off from the other classes I’m taking,” Baez said. “And after the class is over, it encourages me to keep moving – it helps me take the initiative to stay active.”

For students, by students

Before the pandemic forced his engineering communications class online, Rick Evans had never used Canvas, Cornell’s online instruction platform – partly because he finds such platforms too teacher-centric and restrictive.

Around the same time, Evans, director of Cornell Engineering’s Engineering Communications Program, realized his students wouldn’t be able to complete the project he’d intended – developing a communications-related project over the course of in-person visits with members of the nearby Seneca Nation.

He merged the two problems into a single solution: He assigned his students the project of designing two new Canvas sites. He hoped the result would be a less teacher-centric Canvas, more effective at realizing critical learning outcomes while supporting increased faculty engagement.

Whatever the class teams design – projects expected to be completed by the last day of finals – will become the online learning platform for Evans’ fall 2020 courses.

“Part of the goal of the course is to give them the experience of being communication agents – people who can do something with language and have something happen as a consequence,” Evans said. “I hope to have two Canvas sites that are done by students, for students.”

Students began by doing research on Canvas and other online learning services.

“Almost all the literature about Canvas suggests that its use is primarily as a repository. People put stuff up there and give access to the students that way,” Evans said. “There’s a construction there – that teachers are only ‘information givers’ and students are only ‘information receivers.’”

He hoped to be able to change that construction and encouraged his students to investigate. What if Canvas were designed in a way that encouraged more student interaction? Gave students a role in developing or guiding the structure of a course? Changing the format of the platform could alter the way students perceive or experience it, Evans said.

“Canvas is a genre, and like any genre, it constructs identities for both authors and audiences. I thought it might be quite interesting for students to think about what might be the consequences of ‘playing around’ with Canvas a genre,” he said. “And I use that metaphor pointedly, because they should be playing. I hope they’re having fun with it.”

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe