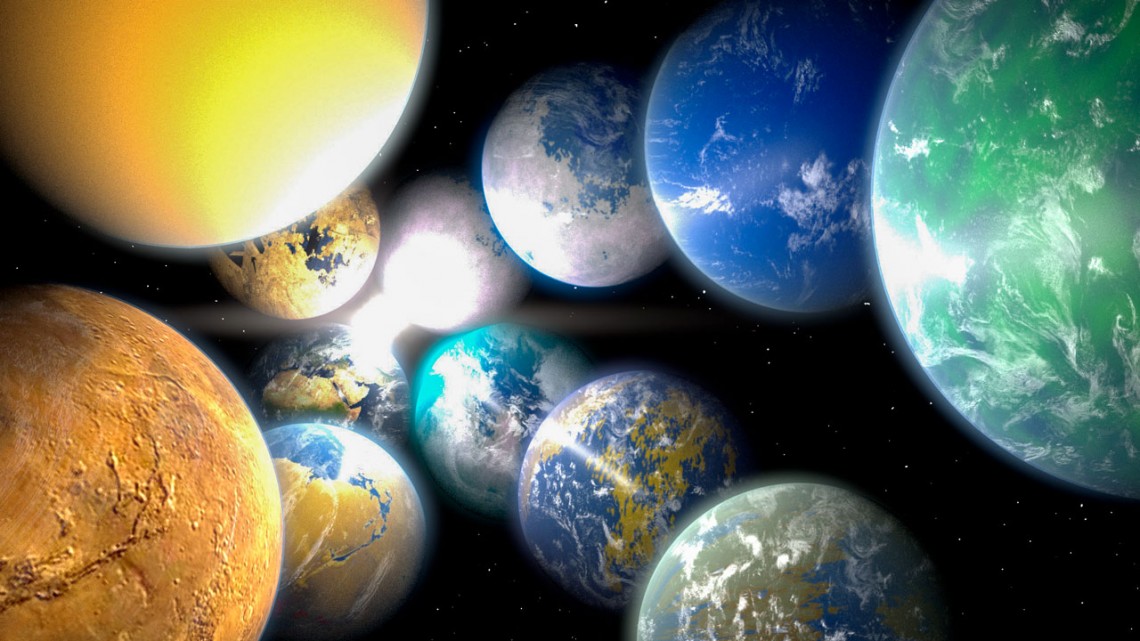

In the AAS Fred Kavli Plenary Lecture on June 1, Lisa Kaltenegger explained how astronomers are discovering an infinite diversity of exoplanets, as artfully depicted here by one of her former doctoral students Jack Madden Ph.D. ’20.

Kaltenegger details diversity of exoplanets in lecture

By Blaine Friedlander

When astronomer Joan Schmelz met then-postdoctoral researcher Lisa Kaltenegger a decade ago at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, the hottest cosmic theme to study was exoplanet exploration.

“That was a strong indication that astronomy was changing in important and fundamental ways,” Schmelz, associate director of the Universities Space Research Association, told astronomers via Zoom on June 1 in kicking off the 236th meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS).

“But like an expert surfer who sees a swell growing on the horizon and knows instinctively that this will be the wave of a lifetime,” said Schmelz, a vice president of the society, “Lisa was in the perfect position to ride the exoplanet wave into the future.”

The future is now for Kaltenegger, associate professor of astronomy and director of Cornell’s Carl Sagan Institute. She gave the AAS meeting’s Fred Kavli Plenary Lecture. “Searching for Habitable Worlds: Challenges, Opportunities and Adventures.”

Kaltenegger told more than 1,300 online registrants – more than double the attendance of any previous in-person AAS summer convention – that searching for life in the universe provides insight on our own planet.

“The thousands of new worlds that we’ve discovered around other stars allow us to not just see them as individual interesting planets, but to discern patterns to understand how planets form, evolve and which of them could harbor life like our own,” Kaltenegger said, adding that among the exoplanets “we have found an incredible diversity.”

More than 4,200 exoplanets have been discovered over the past three decades. Some of the distant solar systems feature hot Jupiters or mini Neptunes; astronomers have found solar systems with planets that are evenly spaced. Kaltenegger conducts research on the newest worlds found every day by NASA’s TESS (Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite) mission.

While Kaltenegger’s peppered her talk with stunning images, she made clear that those depict artistic imagination. “We have the first snapshots of some of these new worlds to add to the family photo album, if you will, but the best photos of exoplanets are tiny dots of light,” she said. “We can glean a lot from those small white dots.”

Kaltenegger and her Cornell research group have created an exoplanet reference catalog – a database of spectral fingerprints – using our own Earth.

“When I think about rocky worlds … it is like a Rubik’s Cube,” she said. “It has a lot of different pieces we need to fit into this big puzzle of what makes a planet habitable and how to spot it.”

“When we see different patterns emerge, we can piece together the patterns to help us understand how a planet works and what we can spot with upcoming telescopes,” she said. “That’s why it’s important create a database for these different worlds.”

Kaltenegger described how using spectroscopy can characterize planets. Astronomers will be able to prioritize follow-up observations and search for exoplanets that have the spectral fingerprints of life – ozone or oxygen in combination with methane, she said, “Of course we would like to see water as well.”

“We don’t have the ships to go to these worlds yet,” she said, “but light travels in the universe for free, so if we catch the light, we can peer into the atmosphere of worlds very far.

“We are standing on the threshold of technology,” she said, noting that the Earth-bound Extremely Large Telescope (proposed first light 2025) and the James Webb Space Telescope (proposed launch 2021) will soon be part of humanity’s exploration tool kit. “We will have the technological means for the first time ever to characterize other rocky worlds – to figure out if we’re alone in the universe.”

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe