Susan Brown, Herman M. Cohn Professor of Agriculture and Life Science and head of Cornell’s apple breeding program, holds an apple variety used for making rose cider.

From seed to supermarket: What does it take to put produce on your plate?

By David H. Freedman

If you were on Cornell’s Ithaca campus last fall, you might have found a few cafes with wooden crates full of fruit simply labeled “Apple A.” The apples have distinctive russet skin dotted with white spots. Take a bite and you’ll get a complex, nutty sweetness that’s not quite like any apple you’ve ever tasted.

So why does it have such an unremarkable name? Because Apple A isn’t ready for the grocery store quite yet. Breeding, licensing and retailing new produce are all complicated processes, and convincing consumers to trade their favorites for something new isn’t much easier.

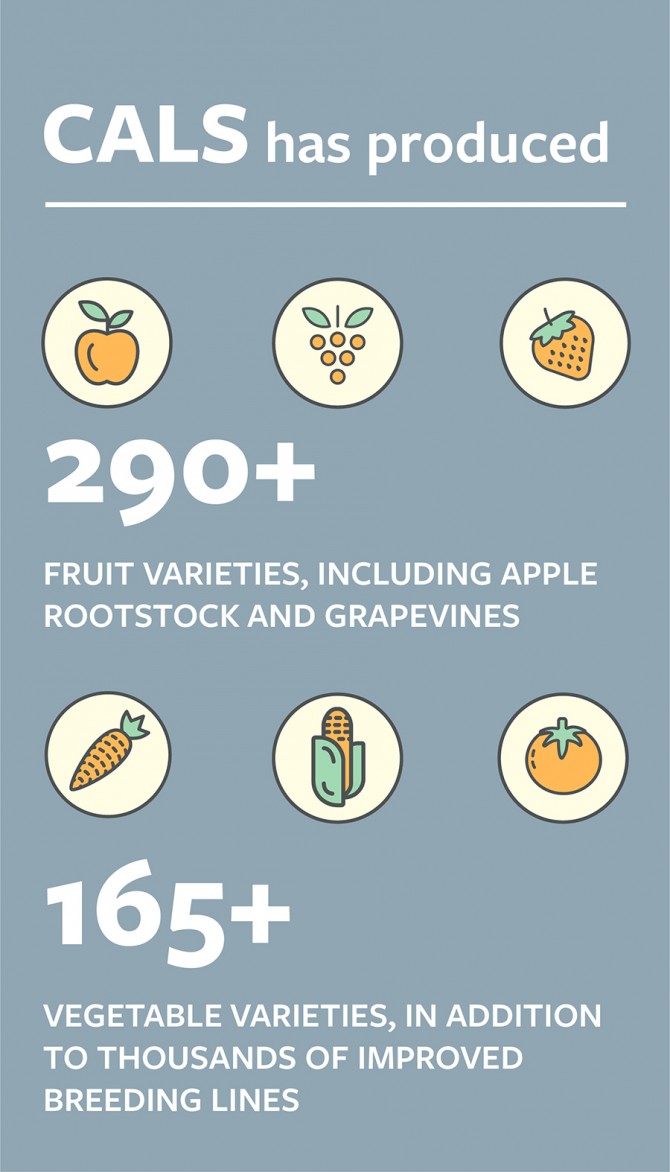

But over the years, the innovative plant breeders at Cornell’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences (CALS) have created more than 290 fruit varieties and 165 vegetable varieties. From breeding new varieties that will wow consumers, to marketing those varieties to get them to people’s plates, they’re offering farmers, producers and consumers foods that taste better, have longer growing seasons and are more resistant to threats from diseases, insects and weather.

Spinning the wheel of traits

When plant breeder Phillip Griffiths started at CALS in 1999, he says, he and his colleagues focused almost exclusively on breeding plants for disease resistance, higher yields and the other traits growers wanted.

Now the bar is moving even higher, says Griffiths, associate professor in the horticulture section of the School of Integrative Plant Science (SIPS). “In recent years,” he says, “there’s been more interest in developing products that are aimed at what consumers want, too.”

This shift has opened the door for CALS breeders to show the creative side of their expertise. “Right now, the food system is wide open to change, unlike at any point in my lifetime,” Griffiths says. “Anything can happen.”

In 2004, Griffiths decided to grow new varieties of tomatoes that would offer consumers more diverse color and flavor choices. “I was originally interested in coming up with a finger-shaped tomato that could be a substitute for baby carrots,” he says. But the new fruit didn’t grow quite the way he was hoping.

When researchers cross-breed plants to enhance or minimize certain traits, it’s a genetic gamble to land the winning combination of characteristics. A plant with one desirable quality, like taste, crossed with a plant that has another ideal trait, like texture, might produce offspring that has one, both or neither of those qualities. And traits can skip generations and reappear months or years later.

“By combining different shapes, I eventually developed tomatoes that looked exactly like chili peppers,” Griffiths said. But he wasn’t discouraged by the odd shape. He was inspired. “Since tomatoes and chili peppers are two of the most popular foods in the world, I thought it might have a lot of appeal.”

This variety still needs a few more years to ensure that offspring remain stable from generation to generation, so that farmers and consumers receive a predictable product. From idea to market, this variety will amount to some 15 years of breeding work.

What’s in a name?

Marketing a new creation also presents a substantial challenge.

One of the biggest obstacles for breeders is that consumers and the food production pipeline don’t recognize specialty crops as unique products.

“I could rattle off 50 different cultivars of butternut squash, but most are sold under the commodity name of ‘butternut squash,’” says Michael Mazourek, Ph.D. ’08, associate professor in the plant breeding and genetics section of SIPS. “You can come up with a better variety, but if people don’t recognize it, you can be stuck clawing for traction and impact in the market.”

Part of the problem is that most breeders’ efforts tend to be invisibly absorbed into the commercial food chain. Researchers might give their budding varieties unique names, says Mary Kreitinger, executive director of the Vegetable Breeding Institute in the plant breeding and genetics section of SIPS. “But unless a seed company markets our variety by name, we usually have no way to track it and don’t know how or where it gets to consumers.”

Mazourek broke through the anonymity barrier by partnering with Manhattan chef Dan Barber and grower Matthew Goldfarb to co-found Row 7 Seed Company. Their goal is to bring diverse produce to farms and consumers by working with chefs who embrace new ingredients.

“I did it to fill a void in the market,” says Mazourek, who gets no money from or equity in the company. “I like to create things that stand out, and we use enjoyment of flavor to drive change.”

Now Honeynut squash – a smaller, more flavorful variety of butternut squash that Mazourek helped develop – has earned name recognition on the national market.

Breeding for the new consumer

Establishing a new variety in the marketplace is still an uphill battle, and not always in a breeder’s best interests, says Jessica Lyga, senior licensing and business development officer at Cornell’s Center for Technology Licensing. “We do market research,” she says, “to see if the new variety would be just another entry among 200 in a commodity market or a shining star that’s clearly better than what’s out there.”

Consumers are willing to try a new type of apple once, says Susan Brown, the Herman M. Cohn Professor of Agriculture and Life Science and head of Cornell’s apple breeding program. But repeat sales determine if a new apple can make a dent in an already competitive market.

For SnapDragon, one of Brown’s best-known apple varieties, the decision to go big was easy. “The first time I bit into it, I said, ‘Oh my gosh,’ and everyone who tried it agreed,” she says. “I’ve never been so confident in a fruit.”

The apple was released in 2015, following the 2014 release of another variety, RubyFrost. Crunch Time Apple Growers, a cooperative open to all growers in New York state, formed a partnership with Cornell and licensed the rights to grow and sell both of Brown’s varieties. Crunch Time’s marketing team then leveraged social media to generate interest among its audiences.

In 2018, Crunch Time doubled the volume of SnapDragon sold over the previous year. It’s on track to double again. RubyFrost is also recording strong, steady growth. SnapDragon has been a hit on the international market, as well, including in Canada, Israel and Vietnam.

CALS breeders aim to help New York state farmers thrive, by making crops more sustainable and produce more diverse, says Mazourek, and CALS researchers work closely with farmers on every aspect of crop selection and growing. “As academics, we want to help understand the world more clearly,” Mazourek says. “But in the end, we want our work to translate into better lives.”

Still, the occasional consumer hit is welcome.

Perhaps the next one is sitting in a wooden crate labeled Apple A.

This article is adapted from the original, “Genetic ingenuity: What does it take to put produce on your plate?” by David H. Freedman, a freelance writer for the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe