Gender gaps in STEM college majors emerge in high school

By Kate Blackwood

Although studies have shown that women are more likely than men to enter and complete college in U.S. higher education, women are less likely to earn degrees in science, technology, engineering and math fields.

In new research, Kim Weeden, the Jan Rock Zubrow ’77 Professor of the Social Sciences in the College of Arts and Sciences, traces the discrepancy in college majors back to gender differences that emerge early in high school.

Weeden is corresponding author of “Pipeline Dreams: Occupational Plans and Gender Differences in STEM Major Persistence and Completion,” published June 3 in Sociology of Education. Co-authors are Dafna Gelbgiser of Tel Aviv University and Stephen L. Morgan of Johns Hopkins University.

The researchers found that gender differences in high school students’ occupational plans – where they see themselves at age 30 – have a large effect on gender differences in STEM outcomes in college, whereas gender differences in high school grades, math test scores, taking advanced math and science courses, self-assessed math ability, and attitudes toward family and work account for only a small percentage of the gap between female and male STEM major graduates.

“Gender differences in academic achievement in high school and in work-family orientation are ‘zombie explanations’: They refuse to die, no matter how weak the empirical evidence for them,” said Weeden, director of the Center for the Study of Inequality.

Gender differences in plans emerge very early in students’ academic careers, Weeden added, “even among students who do well in math and science and have similar orientation to work and family.”

The researchers analyzed data from the Educational Longitudinal Surveys (ELS), a data set collected by the U.S. Department of Education that tracked students who were high school sophomores in 2002 through 2012.

“The ELS cohort is one of the first to complete its schooling after women’s college completion rates began to exceed men’s and when the gender composition of the STEM workforce became a significant focus of policy and discussions about higher education,” the researchers wrote.

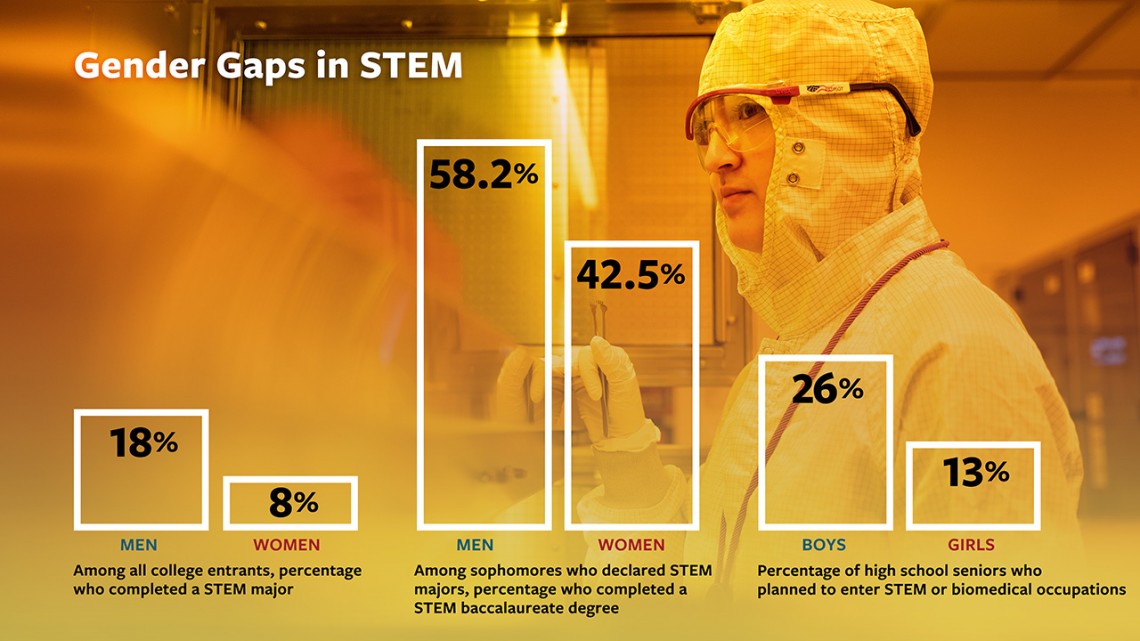

The gender differences in occupational plans are substantial. Among high school senior boys, 26% planned to enter STEM or biomed occupations, compared with 13% of girls, while 15% of girls planned to enter nursing or similar health occupations compared with 4% of boys.

At the college level, gender disparities show up not only among those completing a STEM major, but also among those who persist in STEM after declaring a STEM major as a college sophomore. Among all college entrants, 18% of men compared with 8% of women completed STEM/biomedical majors. Among college sophomores who declared STEM majors, 42.5% of women went on to complete a STEM baccalaureate degree, compared with 58.2% of men.

The results suggest that efforts to reduce gender differences in STEM outcomes need to begin much earlier in students’ educational careers. This is hard to do, Weeden said, because of persistent cultural messages and a gender-segregated adult workforce that reinforce young men’s and women’s beliefs – whether accurate or not – about the types of occupations where they will be welcome and rewarded fairly.

“University-based programs to support students in STEM are worthwhile,” Weeden said, “but they can’t really be expected to reverse all the social and cultural influences on the plans that young men and young women form well before college.”

Kate Blackwood is a writer for the College of Arts and Sciences.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe