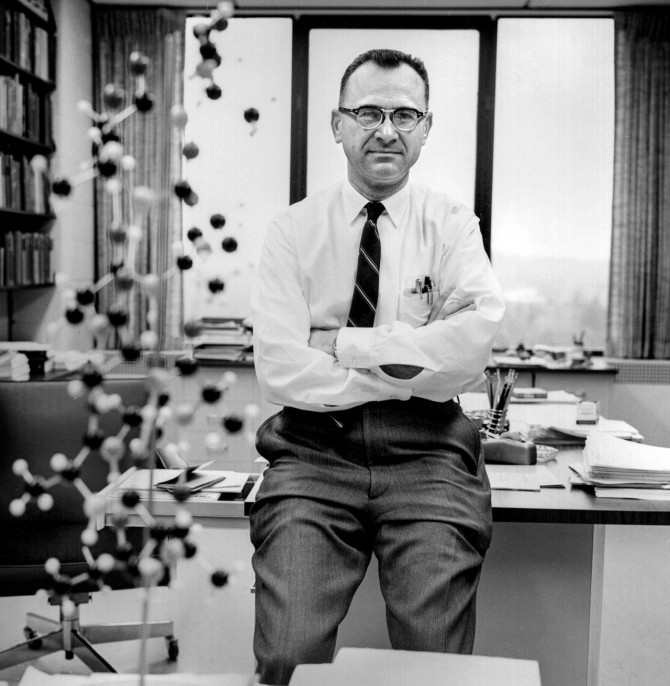

Harold Scheraga, the George W. and Grace L. Todd Professor Emeritus of Chemistry, combined experimental and theoretical approaches to show how amino acid sequences influence the structure, folding, thermodynamics and biological activity of proteins.

Harold Scheraga, protein chemistry pioneer, dies at 98

By David Nutt

Harold A. Scheraga, the George W. and Grace L. Todd Professor Emeritus of Chemistry in the College of Arts and Sciences, who had a profound impact shaping the understanding of protein structure, died Aug. 1 in Ithaca. He was 98.

Scheraga’s career stretched across seven decades and resulted in more than 1,300 publications. Even after he retired in 1992, he maintained a robust research program that many of his peers and students would struggle to match. His most recent paper was published in June.

“It’s amazing to think that Harold’s career has spanned the history of the entire field of modern protein chemistry,” said Brian Crane, the George W. and Grace L. Todd Professor in Chemistry and department chair. “In the 1950s, Harold conducted classic experiments on the basic hydrodynamic properties of proteins, before we barely had an inkling of their complex assemblies and activities that underlie nearly all biological processes. His work touches on nearly every aspect of protein chemistry and biophysics. … He was an incredibly prolific and determined scientist who leaves a body of work that is nearly unparalleled.”

When Scheraga began his academic career in the 1940s, proteins were still very much a mystery in the chemistry community. Scheraga initially distinguished himself by applying experimental physical chemistry to protein science, a field now referred to as protein biophysics. Scheraga’s combination of experimental and theoretical approaches showed how amino acid sequences influence the three-dimensional structure, folding pathway, thermodynamics and biological activity of proteins.

Scheraga was born on Oct. 18, 1921, in Brooklyn, New York, to Samuel and Etta Scheraga. He spent his early childhood in Monticello, New York, where his father, a machinist, opened a store selling radios and musical instruments. Scheraga’s father lost the business after the 1929 economic crash, and the family moved back to Brooklyn. The financial strain during the 1930s was so strong that Scheraga offered to drop out of school to help support the family, but his father insisted he continue his education. Scheraga later credited the Great Depression with shaping his outlook and career aspirations.

Scheraga received his Bachelor of Science degree from City College of New York in 1941, and his Ph.D. from Duke University in 1946, after which he was awarded a one-year postdoctoral fellowship at Harvard Medical School.

Scheraga had early dreams of coming to Cornell because his father’s twin brother, Morris, attended the College of Veterinary Medicine and became a microbiologist. Scheraga himself was hired as an instructor teaching quantitative analysis in 1947; five years later, he began teaching undergraduate physical chemistry.

The connection to Cornell ran through the Scheraga family. Not long after he arrived, one of his younger brothers, David Scheraga ’53, enrolled for mechanical engineering. Scheraga’s wife of 76 years, Miriam, who died in January, worked for Cornell University Library for 30 years. All three of their children – Judith Stavis ’68, M.D. ’72, Deborah Scheraga ’70 and Daniel Scheraga ’73 – graduated from Cornell.

Scheraga became an assistant professor in 1950, associate professor in 1953 and a full professor in 1958. In 1965, he was named the Todd Professor of Chemistry.

In addition to teaching and research, Scheraga made lasting contributions to the chemistry department when he served as the department chair from 1960-67. During this period, he initiated the construction of the S.T. Olin Chemistry Research Laboratory, and he led the department’s expansion into molecular biology and materials science. Among the faculty he recruited was Jack Freed, the Frank and Robert Laughlin Professor of Physical Chemistry Emeritus, in 1962.

“I didn’t jump at the offer, but Harold, in his true style, kept after me until I accepted. It already showed me his single mindedness and focus,” Freed said. “He built up a very strong department with both senior and junior hires, and the department became one of the top 10 chemistry departments in the country. His management skills were exceptional. He was able to make strong judgments and decisions and move the department forward within the university.”

Scheraga loved to travel, but in spite of his frequent trips he was able to maintain a prodigious output of published research.

“Part of his secret was to use his flying time to work intensively on his manuscripts, probably just as intensively as his efforts in his office,” Freed said. “This intense work couldn’t be matched by anyone else in his research group. One of his former students confided to me that he tried to work as intensively as Harold, only to become ill.”

Over the years, Scheraga trained and mentored hundreds of graduate students and postdoctoral researchers, and he maintained close ties with many of his former students. In 1958, as the U.S. raced to catch up with the Soviet Union’s launch of Sputnik, Scheraga was inspired by President Eisenhower’s push for more science education in public schools, and he joined the Ithaca City School District Board of Education, serving a one-year term.

Scheraga was a Guggenheim fellow and Fulbright research scholar, a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, a member of the United States National Academy of Sciences, and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and he received the Eli Lilly Award in Biological Chemistry, among many other honors.

The Scheraga-Burke Meeting Room on the fourth floor of the Physical Sciences Building is co-named in his honor.

He is survived by his brother, David, along with his three children, five grandchildren and four great-grandchildren.

A symposium in Scheraga’s honor will be held after the COVID-19 crisis ends. In lieu of flowers, the family requests that donations be made to the Ithaca High School Harold A. Scheraga Chemistry Scholarship Fund: c/o Daniel Scheraga 70 Clinton St., Tully, NY 13159.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe