Poet’s book finds words for ‘things that leave us speechless’

By Kate Blackwood

In recent months, poet Valzhyna Mort has been a voice in news outlets and on social media during pro-democracy protests in her native Belarus. But the poetry collected in her new book, “Music for the Dead and Resurrected,” is not about a specific political or social subject.

Instead, these poems pick up from where historians stop, said Mort, assistant professor in the Department of English in the College of Arts and Sciences.

“A journalist writes what happened,” Mort said. “But somewhere there is the person who says, ‘I’m still here with my pain, with my loss. Who is there for me?’ I think this is when a poet becomes that companion. Because a poet doesn’t just say what happened. A poet says, ‘How does history feel?’ and ‘Is it even possible to find words?’”

In her third collection published in America (her 2017 collection, “Rose Pandemic,” was published in Belarus), Mort finds words to describe “things that escape language, things that leave us speechless.”

Many of the poems in “Music for the Dead and Resurrected” are rooted in Belarus, present and past.

“Belarus has a history of 250 years of political and cultural fracture,” Mort said. “Current events in Belarus – mass imprisonment, police kidnapping people on the street, torture in police custody, direct threats of execution – have triggered old wounds, old silences. My book speaks to these wounds.”

But the book also speaks about intimate things, she said, touching on “family, apples, Chernobyl, linden trees, bison, Caravaggio, Minsk, sausage, music.”

“In the world where human witnesses of violence don’t survive, any object becomes a witness,” Mort said.

In the poem “Bus Stops: Ars Poetica,” a purse “opens like a mouth” and screams with a human voice. An accordion, which Mort played as a child, appears in multiple poems, as do references to nuclear reactors and voices of women telling stories of the past.

“Having climbed into my lap, the accordion / composes / its heavy breathing,” Mort writes in the poem “Song for a Raised Voice and a Screwdriver.”

In the prose poem “Baba Bronya,” Mort channels memories of her grandmother, a prodigious storyteller: “In the apartment building that stretches for two bus stops, I am a test-child exposed to the burning reactor of my grandmother’s memory. In the first decade of my life, I receive a full dose of her – your – pravda [truth] as a daily injection.”

“Music for the Dead and Resurrected” is in English, but Mort wrote in both English and Belarusian as she drafted the poems.

“I write in two languages at once. I go in between the two drafts and without a hierarchy of original versus translation,” Mort said. “I think of my languages as a kind of storage room I walk through and all of the language is there for me to use.”

Mort also speaks Russian, the first language she learned growing up in part of the Soviet Union. But she never writes poems in Russian; as a colonial language, she said, it “carries a lot of violence in it.”

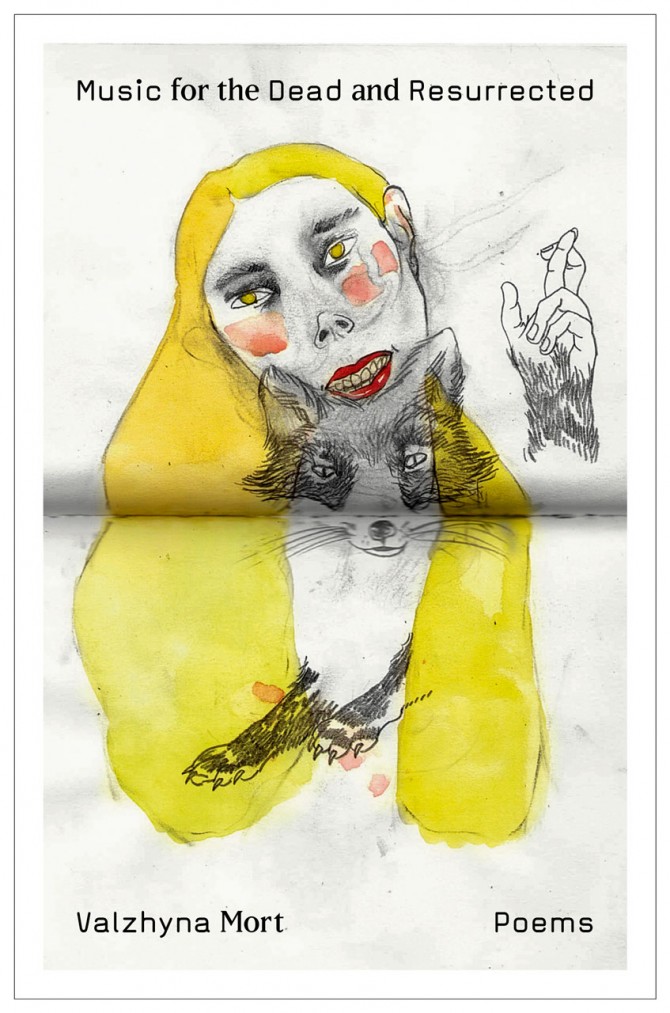

The book’s cover features an illustration by a young Belarusian artist Vasilisa Palianina, who took a poetry class from Mort in Minsk. “She did a drawing in response to one of my poems,” said Mort, who looked through the artist’s entire collection to find the cover illustration. “I was really struck with her work. I recognized something in it. I felt seen by it.”

Poetry cannot be an antidote to horror, pain or loss, Mort said. But it can be a tool of coping.

“It consoles,” she said. “A possibility of precision and clarity for our losses, joys and traumas is a consolation. Language teaches us fear while poetry teaches us how to overcome fear.”

Kate Blackwood is a writer for the College of Arts and Sciences.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe