This rendering of the proposed Waterloo Art Center shows the third floor, with open studios and an atrium.

Good bones: Students revive historic building in Waterloo, NY

By Susan Kelley

Like most people in Waterloo, New York, artist Josh Mull had never set foot in the building at 38 Washington St., even though he had lived in the village most of his life.

“A lot of people in Waterloo don’t know the history of the building,” says Mull, who teaches art in nearby Canandaigua. “People drive by it. But I don’t know that anyone’s really ever thought to look twice to imagine what it could be.”

Perched on the Cayuga-Seneca Canal, the three-story building was constructed circa 1897 by the Waterloo Organ Company, which was well-known for its fine pianos. Decades later, community members would stop in to peruse the wares at Moore’s Furniture store, run by a local family.

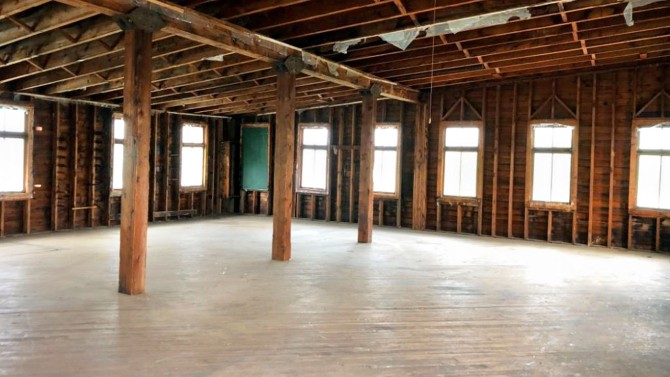

But like so many historic buildings in upstate New York, the once-productive building has been underused for at least 20 years. A can redemption business now occupies a small fraction of the first floor. The rest of the 7,600 square-foot building is vacant. Water has rotted windowsills and damaged the interior. A broken elevator poses a safety hazard and exposed insulation lines the walls. Outside, boards and plastic cover many windows and a door. Peeling paint pockmarks the deteriorating façade.

“I couldn’t even see through the windows because of the dust,” Mull says.

Even so, village officials and the owner, real estate developer Howard Friedman, saw potential for 38 Washington St. to come back to life – as the Waterloo Art Center.

When they offered Mull the chance to check out the building in 2018, he took it.

On the first floor, he saw floor-to-ceiling windows flooding the storefront with natural light – perfect for art displays or community activities. On the second and third floors, exposed wooden beams, intact hardwood floors, open floor plans and enormous windows on all four walls offered a generous blank slate. A small penthouse on the rooftop offers “a helluva view.”

“It just has such a boldness about it,” Mull says. “Walking through those doors, I could visualize the potential.”

A team of nine Cornell design students, many in the College of Architecture, Art and Planning, saw the potential too. In fall 2020, the village of Waterloo asked Design Connect, a student-run community design organization, to design a concept for the Waterloo Art Center.

By the end of the semester, they had delivered.

“I can’t give them enough of a pat on the back,” says Don Northrup, a lifelong resident of Waterloo and the village’s clerk/treasurer. “I just got blown away by how they made it all happen in the COVID-19 environment, in the timeframe that we had. And the product was just incredible.”

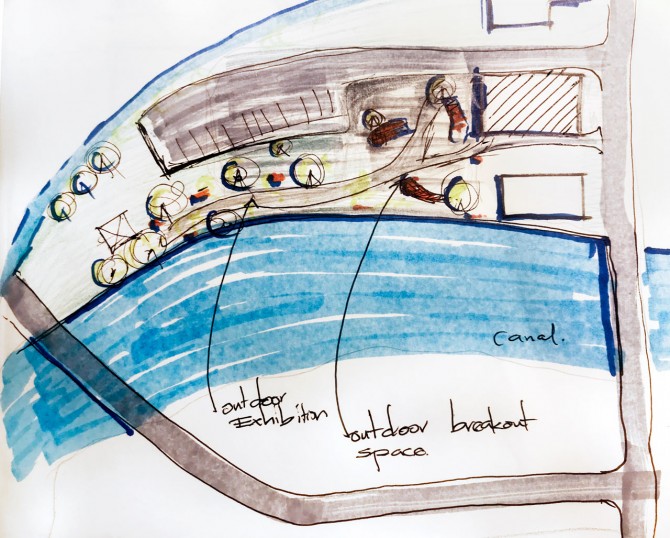

The students conducted research and analysis on the building, consulted extensively with community members and worked up a cost analysis. Their design proposal includes two options: a high-cost, $1.2 million budget and a more modest $875,000 scenario. Elements include new window systems, insulation, a ground-floor exhibition space and bookstore, skylights, a roof deck, a portable stage, two artist residences, 20 flexible studios, ceramic and photograph studios, and a sweeping ground-floor atrium that extends to the third floor.

“It was really cool to see the organic process of the team asking the community these questions and then creating two versions of the design,” says Alex Teller, project manager for Friedman’s real estate development firm, Madison HNJ. “And I think they knocked it out of the park.”

A bigger plan

The redesign is part of a larger downtown revitalization initiative to diversify economic activity and create a sense of place built on Waterloo’s rich historical past. Because Waterloo is equidistant from the northern shores of Seneca and Cayuga lakes, village stakeholders envision the Waterloo Art Center as a destination for tourists traveling between Geneva and Seneca Falls; the village is also an hour’s drive from Ithaca, Rochester and Syracuse. The center would be a two-minute walk from the proposed water taxi that will link Cayuga and Seneca lakes, and a few minutes’ walk from Waterloo’s main street.

Preserving historic architecture is part of the plan too, says Northrup. “It’s like losing a part of the family if one has to be taken down.”

The report could make the Art Center’s potential more tangible to community groups like Waterloo’s Economic Development Council, says Mull, who serves on the council and is a former village trustee.

“I’ve seen people be a little skeptical about [an art center]. ‘How’s it going to generate interest? How’s it going to generate revenue?’” he says. “We have a very well thought-out plan right here. I can’t just shout out an idea and everyone latches onto it. But people can latch onto this report. This creates excitement.”

The report also takes the concept a significant step closer to engineering and construction, says Alex Tranmer, senior project manager with Camoin 310, an economic development firm based in Saratoga, New York, that works for Waterloo. She had seen in village documents that a Design Connect team had worked with Waterloo in 2014, on a design for a vacant lot in the village center; she contacted Design Connect in summer 2020, linking village stakeholders and the students, and coordinated the project.

The report may also be a helpful tool for the village to apply for state funding. “This is certainly a really important step to be able to show that this concept has legs,” she says, “and why it has value, why the state might want to fund a portion of it.”

An opportunity for students

Design Connect also helps students learn tangible skills, such as framing a problem and finding ways to address it in a specific timeframe. It was the first time Grace Cheng, B.Arch ’21, who led the team remotely from her home in Taipei, Taiwan, had the chance to work on a renovation. “I’ve always been interested in public, cultural buildings,” she says. “It’s pretty interesting to see how the structure will be transformed into a cultural one, because it has been mostly commercial/industrial in the past.”

Working with a preexisting building came with its own challenges, “like maintaining the history of the place, and respecting the context, but still making the building new and exciting and contemporary,” says Nasha Gitau, M.Arch ’22, who worked on the project remotely from Ithaca.

The students were unable to visit the site due to the COVID-19 pandemic, so Michael Tomlan, Ph.D. ’83, professor of city and regional planning who teaches the Design Connect course, visited the site for them, taking measurements and photographs.

Importantly, Design Connect projects offer students the chance to interact with community members outside of Ithaca – often for the first time, says Tomlan. “The reality is the contexts of the towns are so radically different from the students’ that they really have to stretch a bit.”

That’s what Cheng found most fulfilling: being able to understand the community they were designing for.

“A lot of the people who joined Design Connect wanted to have the experience of working with real clients and delivering a result that they are happy with,” she says. “At the end of the day, we’re serving them.”

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe