Mary Nichols, former chair of the California Air Resources Board, will be a Visiting Senior Fellow at the Cornell Atkinson Center for Sustainability.

Mary Nichols ’66 brings fresh air to Cornell Atkinson

By Blaine Friedlander

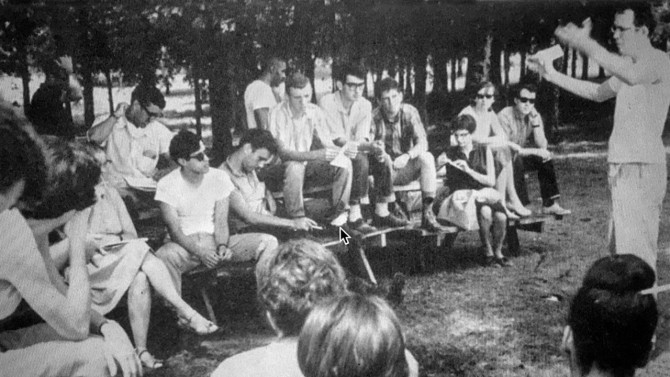

In the summer of 1964, Mary D. Nichols ’66 joined 30 other Cornell student volunteers to explain civics and to register Black citizens as voters in a deep-South Tennessee county. She traces her passion for justice and the environment to that moment.

“That experience is what led me eventually to law school and to environmental activism,” said Nichols, now an internationally acclaimed environmental regulator who has spent her career working for California governors and U.S. presidents to cool a warming Earth and to provide fresh air.

“Cornell provided an atmosphere of seriousness and commitment on the major issues of our time,” she said. “We had lots of intellectual and moral support … and also a sense that we young people could make a real difference.”

Nichols will continue making a difference as a Visiting Senior Fellow for one year at the Cornell Atkinson Center for Sustainability, and she will join the Cornell Atkinson Advisory Council for the next three years, the center announced March 10.

“There is no one in the United States who has had a greater impact on the improvement of air pollution standards, and the way those high standards affect both human health and climate change, than Mary Nichols,” said David M. Lodge, the Francis J. DiSalvo director of Cornell Atkinson.

Nichols has served as chair of the California Air Resources Board (CARB) – the state’s powerful air-pollution and climate regulatory agency – for Gov. Jerry Brown from 1975-1982 and 2011-2020, and for Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger from 2007-2011.

Under Nichols’ leadership, CARB crafted and enforced regulations that slashed air pollution from cars and light trucks by more than 99%, paved the way for advanced biofuels, and blazed the path for a transition to a fully electrified transportation system.

As a Visiting Senior Fellow, Nichols will meet virtually with faculty, students and university leadership to train sustainability scholars, promote carbon capture and sequestration, and discuss the future of the workplace for a just transition to a greener economy.

In 2019, Nichols convinced automobile makers Ford, Honda, BMW of North America and Volkswagen Group of America to improve car emission standards, while the White House attempted to roll back those standards.

“Having an impact on air pollution regulations in California is a big deal all on its own,” Lodge said. “But it’s actually been a role in which Mary has had a huge impact on U.S. national policy, because the Clean Air Act of 1970 assigns a unique and powerful role for California.”

Lodge explained: “California sets emissions standards for vehicles sold in California, and under the federal Clean Air Act, other states may require California standards rather than the weaker federal standards for new cars and heavy duty engines sold in the states.”

With states representing over 40% of the new car market that follow California, the standards set by the California Air Resources Board become de facto national standards, Lodge said.

“When California began to set emissions standards for carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases beginning in 2004,” said Lodge, “they also achieved a major reduction in fossil fuel consumption, because the lion’s share of greenhouse gas emission reductions came from improved fuel economy.”

Nichols served as the assistant administrator for air and radiation at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in President Bill Clinton’s administration. And she helped to get automakers to cooperate in achieving cleaner air during President Barack Obama’s administration.

After her last California term ended Dec. 31, 2020, Nichols – who had earned her law degree at Yale in 1971 – returned to her post as a professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, Law School. She also holds a visiting appointment at the Columbia University Global Energy Program. Nichols also serves as the vice chair of the China-California Climate Center and co-chair of the Commission on the Future of Mobility.

Long-time Ithacans and Cornell alumni may recognize Nichols’ name. Her father, Ben Nichols, was a long-time Cornell professor of electrical engineering and the three-time mayor of Ithaca; her mother, Ethel Nichols, taught in the Ithaca school system, and was later elected to local office as a member of the Board of Aldermen and later as a Tompkins County Board member.

“Of course, growing up in Ithaca I was surrounded by natural beauty and I spent time in the outdoors,” Nichols said. “But my environmental career is largely an outgrowth of my long-time interest in civil rights and economic justice.”

Mary Nichols entered Cornell in autumn 1962. She had planned to major in the classics, like Latin and Greek, but turned instead to Russian Literature, which she believed was more relevant for her.

“I wanted to be free to take creative writing and drama classes and also spend time on my real passions,” she said, “which were writing articles for Cornell publications director John Marcham ’50 and editing a campus literary/political magazine called The Trojan Horse.”

The real turning point in her Cornell education, she says, came in 1964, as a result of participating in the Cornell-Tompkins County Committee for Free and Fair Elections in Fayette County, Tennessee. The group was organized by Cornellians, and they took Nichols and other Cornell students to encourage and help Black adults register to vote in the Jim Crow South.

White citizens in Fayette County could register as they pleased, but Black citizens were prevented from participating in elections by a variety of discriminatory rules, including having to drive long distances to register at a single county office that was open only for a few hours on Wednesdays.

The Cornell students drove on unpaved backroads during the week and attended church services on Sundays, talking to Black residents – mostly tenant farmers or domestic workers who earned $1.50 a day – about their right to vote.

The students would come back to pick up those residents who agreed to take a day off from work, in order to stand in line outdoors in the hot sun for hours, only to be turned away when the county clerk decided to close up for the day.

On June 23, 1964, Nichols, Tim Hall ’64 and graduate student Gerald Surrette arrived in Fayette County in a “temperamental ’56 Ford,” Nichols said.

It was the same morning that America woke to the news that three men – Cornellian Mickey Schwerner ‘61, James Chaney and Andrew Goodman – also conducting civics education and promoting voter registration, had been murdered in Mississippi, not far from the Tennessee border.

Nichols recounted in the Cornell Alumni News how Cornell graduate students like John Heawood and Ron Schneider, Ph.D. ’66, were falsely arrested for visiting a sharecropper’s home. In fact, Heawood was later beaten after his car was forced off the road – something that happened often then.

“Like soldiers in combat,” Nichols said at the time, “we were very sure nothing would happen to us.”

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe