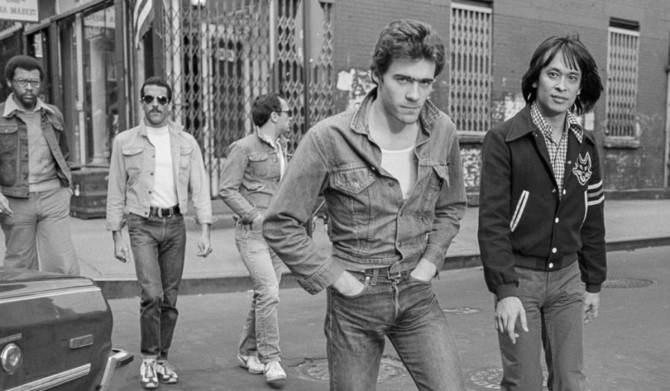

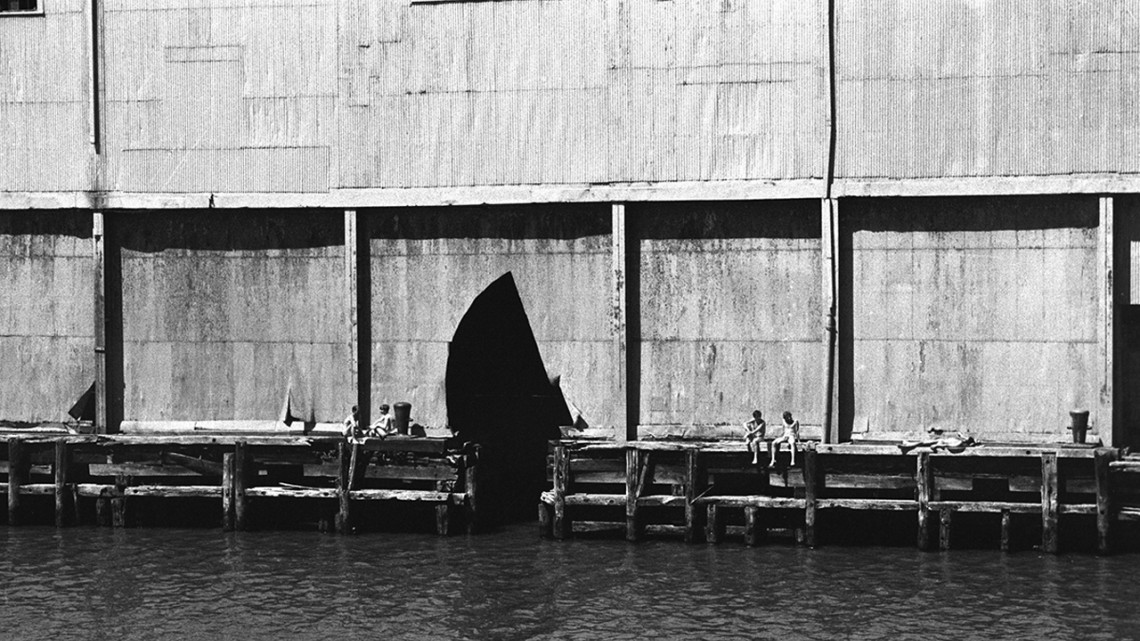

Photographer Alvin Baltrop (1948-2004) documented life at the Hudson River Piers, a declining industrial area of Manhattan occupied largely by queer people in the 1970s and 80s, pictured above with a view of Gordon Matta-Clark's Day's End.

News directly from Cornell's colleges and centers

Chusid, Segade, Warke discuss queer / queering spaces

By Edith Fikes

AAP faculty, Jeffrey Chusid (JC), chair and associate professor of CRP; Alexandro Segade (AS), assistant professor of art; and Val Warke (VW), associate professor of architecture share thoughts on constructing and deconstructing conceptual and physical aspects of queer space — a topic around which they've framed a new cross-disciplinary seminar at the college. Conversations with planning students Harman Singh Dhodi (M.R.P. '21), Matthew Reyes (M.R.P. '21), and architecture student George Tsourounakis (M.Arch. '21) about gender and sexuality in spatial planning, design, and experience shaped Queer Space / Queering Space, a class that considers the topic from the different perspectives of artists, architects, and planners.

Beginning at the beginning, you pose a series of questions to open group discussion: "What is queer? What is space? What are queer spaces?" And so, briefly, how would you define queer, space, and queer Spaces?

AS: There are both practical and conceptual ways to address this question. While we found examples in all our fields of very queer spaces — in the sense that they create the conditions for reconsidering received notions of gender, sexuality, even phenomenology and perception — we also found that, for the most part, it is how people perform within these spaces that make them queer. Hence, the notion of 'queering' actively subverts heteronormativity, making space for queerness and queer people.

Queering space creates conditions for transgressing what are seen as fixed categories — such as gender and sexuality, or in some cases, intersections of racial and ethnic identities — that we do not necessarily see in the dominant culture. Of course, while places like gay bars can be liberatory spaces that bring people together; they can also be extremely exclusive, discriminating against uninvited gender identities, sexes, and races. We have to ask: are spaces that do that really what we would consider Queer spaces? These definitions shift.

JC: To answer this as a two-part question: What is Queer; what is Space? Both words can be deconstructed. In this phrase, Queer can mean spaces that have long been associated with queer people or activities, especially sex — such as gay bars or bathhouses, what some writers call the architecture of desire. But there are also theaters or design studios — workplaces in which queer people collect out of proportion to their percentage in the general population, or even, closets and washrooms — spaces in the home that, since Victorian times, have been associated with hiding, with the body, with things better left unseen or unsaid.

And then, there is the word space that can mean a physical space in the world or perhaps a theoretical or metaphorical concept of place. The former we understand easily enough; the latter is more common in the realms of cultural theory — when we mean a kind of intellectual or social area within the larger context of practice. This might include artists who inhabit a queer space in their medium, say, photography. Or, the houses of Harlem's ballroom culture as depicted in Paris is Burning, or on the show, Pose, which actually can be both physical and metaphorical.

Or, we can see space through a post-structuralist lens that sees space as more constructed than given. Jon Binnie wrote: "Space is not naturally authentically 'straight' but rather actively produced and heterosexualized." Think of the lawn in Tiergarten Park in Berlin where men go to sunbathe naked. It is a queer space because of the actions of the men who claim it, use it, and effectively produce it as an island of queer liberation within the greater heteronormative area of the park.

I do think, though, that it is worth noting that queer people, like everyone, do not adopt a single identity their entire life. Especially as queer people marry and / or become parents, or age out of prime cruising years, the nature of their queer space will change — much as the nature of queer neighborhoods has been changing.

How do the three disciplines of Architecture, Art, and Planning address these questions differently?

AS: Contemporary art has a way of appropriating concepts from theory, politics, or popular culture and applying them to artworks in ways that may feel counterintuitive. I hope this class can connect the idea of queerness back to queer artists and the communities they come from. So, I am introducing the students to work by queer artists who have invested in queering space — whether through social practice, performance, video, installation, or public art. In so doing, we can see a diversity of aesthetic approaches, and while one can trace lineages and legacies, it is also evident that there is no singular way of making queer art or queer space.

JC: Planning looks at the future of (a) place, and of its inhabitants, and then seeks to implement designs and policies that are intended to make those places function better — more equitably, more sustainability, more justly, more efficiently. So the planning perspective in this class ranges from questions of land use (the licensing of bars or dance clubs, for example), to alternative housing models (from communes to retirement communities for queer people), to economic development (think: LGBTQ tourism), to the identification and preservation of sites important to queer history. There is also the performative nature of queering space associated with parades and festivals, or demonstrations and protests to consider.

VW: And architecture tends to look toward its past in anticipation of the potentials of its future. I suspect that queerness, as a radical agitation of the inertia of cultural norms, has been an essential aspect of major architectural shifts throughout history, not to mention of architecture's roles within social actions. This is why I mention the possibility of proto-queer space. Could the Medici Chapel, for instance, be seen as proto-queer?

At the same time, it's clear that the most effective of architecture's recent engagements of queerness have been primarily at the level of the installation. One thinks especially of the Cruising Pavilion by Mateos, Myrup, Perrault, and Teyssou at the 2018 Architectural Biennale in Venice, which nevertheless found itself caught between a nostalgia of sorts for the intense physicality of the labyrinthine backrooms of cruising bars — almost completely eradicated by HIV and COVID —and digital displays of today's predominantly online proxies for sociability. In this course, and to Alexandro and Jeff's initial points, we're beginning to see that it is the performance of activities within often pre-existing spaces that most contribute to the queerness of space. It is often the eccentric re-occupation and disjunctive functionalization of relatively naïve constructions, like piers, neighborhood bars, warehouses, streets, alleys, and parks, that seem to most define the queering of space.

I think architecture has a great amount to learn from these operations; that is, of queering as a theoretically operative, productive technique for the provision of spaces that have the potential for radically altering and subverting perceptions and preconceptions through their anticipation of non-normative occupations, and to redirect architectural spaces away from their fealty to a dominant economic and racial group, with their proscribed customs and rules of decorum.

Queer spaces reach across a spectrum of scales that range from the personal and intimate, to the city and public space, to larger geographies and the global. If there are different ways of thinking through queer space within the disciplines, where do they intersect or overlap at certain points on the spectrum of scales?

AS: The disciplines intersect in the spaces themselves, and in the bodies of the people who move through them.

JC: Our topics are often overlapping, and spill easily from one discipline to the other, from one scale to another. For example, we were looking at Wu Tsang's film Wildness and we quickly went from looking at the act of making both the event and the film to issues of immigration, policing, economic and physical survival, and global diasporas. And cycled back to the personal.

VW: Architecture's scales of operation clearly tend to be located between those of art and planning; and by scales I mean both their obvious physical scales as well as their scales of agency and of requisite public engagement. At the same time, all three departments involved here share concerns with the intellectual and environmental qualities of life, as well as obligations to develop critical attitudes toward society and culture.

Alexandro, you are an artist, Jeffrey a planner, Val an architect — do your practices and / or scholarship address gender, sexuality, and queer space? If so, can you briefly discuss how?

AS: My work addresses how group identities are formed. The performance collective My Barbarian, which I founded in 2000 with Malik Gaines and Jade Gordon, was a way of bringing queer cabaret and feminist performance into contact with what we saw as a very sterile white cube gallery context. A more recent collaboration, A.R.M., explicitly looks at gay histories and connects them to contemporary sexual cultures, as in a series of projects re-enacting photographs from Fire Island in the 1950s. A.R.M., which is a collaboration of three artists, including Gaines, Robbie Acklen, and myself, staged Blood Fountain in 2019, a temporary, performative anti-monument on the High Line, in order to memorialize the ongoing struggles with HIV / AIDS faced by vulnerable populations, and the legacy of the AIDS crisis in the contemporary queer consciousness. In my solo work, the sci-fi multimedia piece Future St., a kind of gay 1984 or Brave New World, I ponder the future of sexuality in a speculative clone culture, where the cloning is real. And finally (whew!), in my graphic novel, The Context, I re-imagine the superhero team as a queer space for a multiplicity of bodies to come into contact with one another.

JC: My professional work and my teaching have only tangentially touched on queer issues. But in fact, the first class I ever taught, as a student at UC Berkeley in the late 1970s, was as a member of a nascent gay and lesbian student organization in the college of environmental design. It was a graduate seminar that attracted students from across the campus and was impactful for those who were involved in teaching, as well as for those who took the class. For me, this class was an opportunity to circle back to issues and topics that are both important to me personally, and, in the political and social environment of today, part of a broader quest for civil rights, respect, and a more diverse and inclusive world.

VW: I see both my work in genre theory and my related interests in fashion theory as directly applicable to queer space, both in terms of the physical aspects of generic indices — what makes a gay bar a gay bar and not a biker bar, for instance (though the differences are sometimes quite subtle) — as well as the critical obligation one has to serve both as an empathetic agent and as a potentially external provocateur. I suspect the creative act originates from an ability to see both within a system and outside that system. Genres always appear to be working within boundaries even as they ultimately aim to transgress them. Where is the discussion, or what are some existing practices in and across the disciplines of architecture, art, and planning that are happening now around the topic of Queer spaces?

Where is the discussion, or what are some existing practices in and across the disciplines of architecture, art, and planning that are happening now around the topic of Queer spaces?

AS: Guest speakers are central to this class. We started with Jeremy Atherton Lin, author of Gay Bar: Why We Went Out (2021), whose book does an amazing job of weaving all these disciplines together in a memoir, no less. Cornell Professor Karen Jaime's work on nightlife also offers a wonderful lens through which we consider these questions. I have invited MoMA curator Thomas Lax to discuss their projects, which bring queer and BIPOC aesthetics into a rich and critical dialogue. Artists Morgan Bassichis and A.L. Steiner will discuss their artwork in light of a utopian impulse in queer separatist spaces. We will also be looking closely at the legacy of the late, great Felix Gonzales-Torres and his contemporary, the photographer Zoe Leonard, and, at how artists have used the gallery itself to create queer spaces. And, we will be watching Wu Tsang’s film Wildness (2012), which brings together all of these disciplines in an East Los Angeles, Latinx trans bar.

JC: I invited Cornell public history professor Stephen Vider to talk to us: he has a new book on queer domesticity coming out now. Another speaker, and a leading figure in queer thinking, especially around media, is Katherine Sender, another Cornell professor speak about Samuel Delaney’s twin essays, Times Square Red / Times Square Blue. I am also bringing in a first-people's writer and thinker on the intersection of queerness and environmental consciousness, Gordon Brent Bochu-Ingram (a member of the Salish, from British Columbia). Finally, I am bringing the photographer Sunil Gupta, who lives in India and the UK, and has had a long career documenting queer people around the world, and in advocacy efforts for queer rights in India. He will be joined by Aditya Ghosh (M.Arch. '12), a Cornell architecture alumnus, now working for FX Collaborative, who, besides being a writer on issues around the gay Indian diaspora, is a cofounder of the Buildout Alliance, an organization that works to create "a building design and construction industry that universally values inclusion, where LGBTQ professionals work openly with pride, and where everyone has access to equal opportunities and a diverse professional network."

Thinking beyond the disciplines, how might bringing scholarship, discourse, or practices that are external to the architecture, art, and planning disciplines be productive or generative? Or, what could broadening the scope of collaboration do to create different spatial experiences for people?

AS: I have found that the best way for me to make a contribution to any field is to open its borders, challenge its boundaries. Not to reproduce what is already in the discipline, and re-enact its edges, but to challenge them. Discipline is a funny word that way, suggesting a rigorously policed area of expertise. I'm not into that, even as I acknowledge the need for a sustained inquiry, using whatever methods available, in order to understand how culture is produced. But I’ve never been super into canons. Canons aren't queer.

VW: Precisely. As I've suggested, I believe that apparel design, for example, where heteronormativity has consistently been challenged, is an important activity to bring into the discussion. Also, it's fascinating how often types of publications, and literary, theatrical, film, and musical genres have become entwined within the various presentations and discussions throughout the course. Disciplinary boundaries necessarily seem fluid. Since queer space is ultimately something that's performed, I suppose it's not surprising. Similarly, architecture always needs to be performed. As the literary theorist Paul Hernadi said in his Cultural Transactions: Nature, Self, Society, "By…realizing the transactive potential of a building, we perform it, so to speak, just as musicians perform a score or reciters of a verbal inscription perform a text."

JC: For me, there are two important goals for this class. The first was to finally formally address the subject — long overdue, for this we should give proper thanks to the students who coalesced around the idea as part of the college's diversity and inclusion initiatives. The second was to break down the almost insurmountable walls that exist between our three departments by making this a class offered by and co-taught by faculty from art, architecture, and planning.

At the same time, we have to understand just how much queerness is political. Even as we are citizens of a college that enthusiastically made a queer space course the first instance of a collaboration between all three departments, in many countries around the world, this course could not even be offered. Across the globe, queer people are having their rights curtailed, they are being assaulted, imprisoned, tortured, and even murdered for living their true selves. We should remember them even as we celebrate being gathered together here today.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe