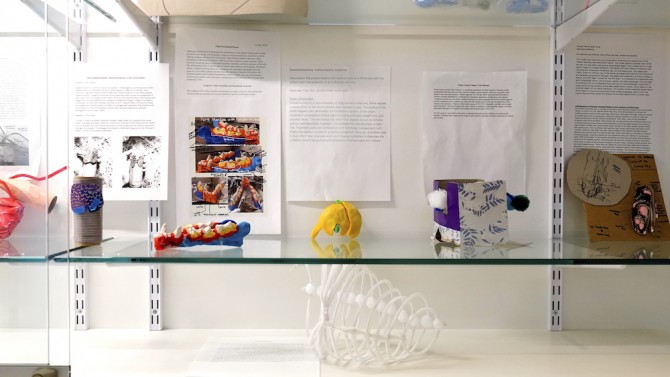

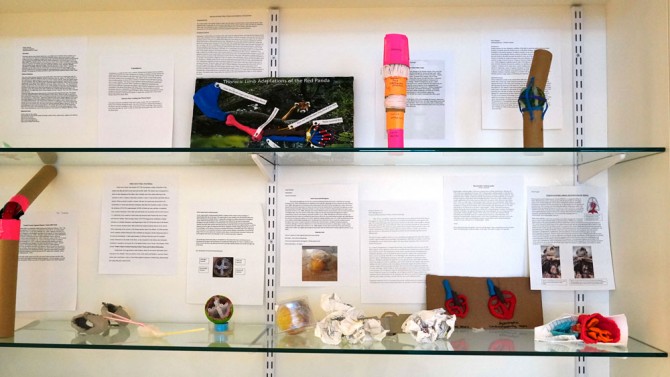

A wide variety of homemade anatomy models created by first-year veterinary students on display at the Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine.

News directly from Cornell's colleges and centers

Pandemic anatomy course inspires student creativity

By Melanie Greaver Cordova

First-year students at the Cornell College of Veterinary Medicine (CVM) studied anatomy a little differently this year. While virtual learning has become second-nature at this point in the coronavirus pandemic, senior lecturer Dr. Paul Maza, like most faculty at CVM, has found a way to infuse an interactive energy into his semi-virtual course Anatomy of the Carnivore, with a project lightheartedly entitled QuarantinAnatomy.

Maza tasked students with creating anatomy models of topics they wrote about in one of their assignments using only materials that were easily found at home. “It was meant to increase the students’ comprehension of the anatomy regarding their specific topic, as well as to have fun and give a nod to our current situation of staying at home so much during the pandemic,” says Maza.

For this course, lectures were virtual but students still had in-person dissection laboratories. Students write literature review papers on topics of feline and canine medicine and surgery, emphasizing clinical anatomy. They also give presentations on anatomical adaptations of non-domestic carnivores, demonstrating how carnivore species have unique anatomy that helps them survive and thrive in the wild. In more conventional times, students would be interacting more frequently in person with the models available at CVM.

For first-year student Chloe Pham, creating her model was no easy feat, as it meant scouring the house for items that could recreate the anatomy of pectus excavatum — a congenital chest deformity where an animal’s ribs and breastbone grow inward.

“I considered the functional purpose of the anatomic parts I was attempting to recreate — vertebrae, ribs, sternum, cartilage, etc. — and tried to think of materials that could replicate those functions in a model,” says Pham. For instance, Pham used Styrofoam to represent vertebrae and pipe cleaners for ribs. “The cartilage model of ribs is that they’re initially flexible, and even after birth the bonier ribs are still malleable. I felt that of my at-home materials, flexible pipe cleaners were an apt representation of this kind of flexibility.”

Pham went through some troubleshooting to settle on the different components, and found that trial-and-error helped her appreciate the harmony of an animal’s anatomy. “For instance, initially I tried using Play-Doh to form my vertebrae instead of Styrofoam, but I was unsuccessful because it was far too heavy and the rest of my model couldn't support the weight,” Pham says. “Although it’s a bit of an oversimplified connection, I related that issue to how in the body different structures need to work together perfectly for good health, and this furthered my appreciation of the sophistication of our anatomy.”

Indeed, Maza has seen students in the class learning material in uncommon ways compared to the typical in-person course, highlighting the resilience and adaptability demonstrated by Cornell’s veterinary students in the last year.

“There is evidence that viewing low-fidelity anatomy models has helped anatomy students learn specific topics,” says Maza. “Most students in this particular class have also commented that creating the low-fidelity models themselves has increased their learning.”

Pham found that seeing how other students in the class brought their projects to life was informative in understanding each disease and condition. As most of their learning and testing has happened in front of a screen, it was also a welcome creative approach to coursework. Says Pham, “Model making was a nice break from the ways we are usually asked to study and demonstrate our understanding.”

Melanie Greaver Cordova is assistant director of communications at the College of Veterinary Medicine.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe