Cornell's College of Human Ecology is celebrating the completion of PolyForm, a 34-foot-wide, walk-through installation designed by Jenny Sabin, professor of architecture in the College of Architecture, Art and Planning, as a centerpiece of the newly renovated Martha Van Rensselaer Hall.

PolyForm celebrates mission, spirit of Human Ecology

By James Dean

A burst of color – sometimes purple, green, yellow or blue – now greets visitors approaching a busy thoroughfare outside Martha Van Rensselaer Hall (MVR).

The source is PolyForm, a public art pavilion designed by Jenny Sabin, the Arthur L. and Isabel B. Wiesenberger Professor in Architecture in the College of Architecture, Art and Planning (AAP), and her practice, Jenny Sabin Studio. The project serves as a new gateway to – and symbol of – the College of Human Ecology (CHE).

From a distance and from within, passersby can explore the square structure’s laminated glass walls and jewel-like stainless-steel modules, whose colors and reflections change depending on the time of day, weather and a viewer’s orientation.

While its cutting-edge design points forward, PolyForm complements CHE’s historic MVR building, which recently underwent a major renovation. It was during planning for that modernization in 2013 that the college, then led by Alan Mathios, professor in the Department of Policy Analysis and Management, first approached Sabin.

The vision: A piece that evoked and celebrated CHE’s interdisciplinary, human-centric mission spanning science, technology and design, and the connections between the natural, social and built environments.

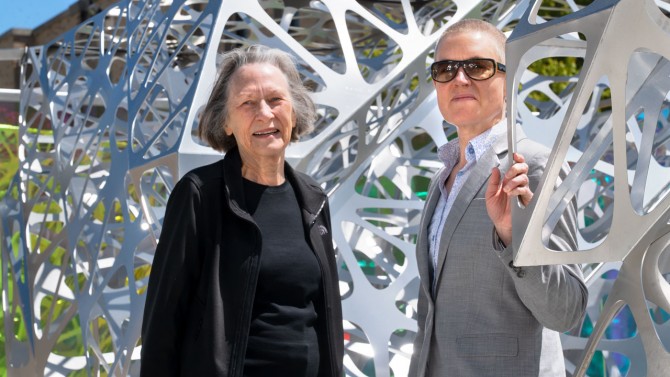

“We wanted to use art in addition to the architecture of our buildings to express the vibrance and integration of the programs and subject matter of the college,” said S. Kay Obendorf, M.S. ’74, Ph.D. ’76, professor emerita of fiber science and apparel design and a driving force and inspiration behind the project eight years in the making. “We sought to respect and honor our past while communicating the energy and direction for the future.”

Teams recently finished assembling the permanent installation measuring 38 feet long on each side and nine feet tall at the corner of Garden Avenue and Reservoir Avenue, at the top of the west path along MVR and across from Bailey Hall. Already, students and others walking around – or through – the 1,500-square-foot site frequently stop to study and take pictures of it.

“My hope is that people are inspired to pause, to take a moment in their busy days, and that it creates curiosity and a sense of wonder and playfulness,” Sabin said. “To see how people are interacting with it and their excitement – for me, that means it’s a success.”

Rachel Dunifon, the Rebecca Q. and James C. Morgan Dean of CHE, said she was pleased to welcome PolyForm and the cross-college collaboration it represents before the close of an academic year reshaped by the pandemic.

“It’s a joy to be able to celebrate PolyForm and to experience it in the dynamic way that this installation allows – something unique to each participant and influenced by the environment around us,” Dunifon said. “This sculpture represents the powerful things that happen when great minds and ideas from across campus come together and is a wonderful symbol of possibility and hope going forward.”

PolyForm is not a literal translation of human ecology, Sabin said, but embodies its themes through a dynamic interplay of light, color and shadow that works across scales.

“By bridging the nano scale to the human scale through advancements in digital fabrication and emerging materials,” she wrote in an artist statement, “this project promotes communication and active exchange across disciplines.”

Designed entirely digitally, the project showcases two main creative elements: “structural color,” and the cellular modules of stainless steel.

Structural color is achieved with a dichroic, or wavelength-dependent thin film laminated to the tempered glass panels. Light reflecting from and refracted on to the film changes color and grows warmer or cooler, more opaque or transparent, she said, not based on pigment but on how the film selectively interacts through interference or reinforcement of certain wavelengths of light at the microscopic scale. The experience thus generates responses from both the materials and from viewers.

“A key component is how we perceive those subtle to dramatic changes of light and color within the material itself,” Sabin said.

The process reflects what Sabin said is one of her driving design questions: How might buildings and their materials respond and adapt to their local environments like organisms do in nature?

PolyForm’s glass perimeter introduces it as a familiar rectilinear form, like buildings across campus, Sabin said. But upon entering either of the paths bisecting it, the experience changes into something more organic, fractured, crystalline.

“In those transformations, as you move through, you get the sense of being embedded in the project,” Sabin said.

The polished stainless-steel modules occupy quadrants in PolyForm’s interior. Each slightly different, the modules began as sheet material that was waterjet cut with holes of varying shapes – moving from larger to smaller – then folded along precise lines into bespoke cells that were welded together.

Each cut and fold executed by Geneva, New York-based Vance Metal Fabricators Inc. was carefully modeled by Jenny Sabin Studio through simulations and prototypes to test their effects, then uploaded to digital fabrication files.

“It’s a project that blurs the lines between art, technology, design science and architecture,” Sabin said. “It’s not an object, but a space that has a presence. It operates as a node in the environment to encourage community participation.”

On a recent sunny afternoon, the walls reflected their surroundings, varying hues and fragments of the interior, and projected multicolored geometric shadows on the sidewalk. In contrasting sections of glinting silver and matte gray, the modules cast variegated shadows.

Daniela Rochez ’21, a global and public health sciences major in CHE who was en route to MVR, said she’d enjoyed seeing PolyForm and hadn’t realized it was a permanent fixture.

“I like the architecture and design of it,” Rochez said. “If it was here a little sooner, I would have taken my senior pictures here.”

PolyForm transforms at night. In-ground lighting along the interior perimeter and within each quadrant illuminate the modules, creating new blends of color and patterns of light.

Ruoshui Wang, a doctoral student in the field of theoretical physics, visited with a friend on a recent evening to take pictures. She said she appreciated the symmetry of PolyForm, found in many structures in physics.

“I also really like that the colorful glass walls almost serve as cinematic filters,” Wang said, “which allow you to look at familiar buildings on campus now with new perspectives.”

PolyForm is one of more than two-dozen public art installations on campus, but its scale and long-term presence necessitated extensive reviews, including the first by a new campus committee established to evaluate such work. In addition to the Committee on Outdoor Art at Cornell, the Cornell Council for the Arts, Building and Properties Committee and Campus Planning Committee approved the plans.

PolyForm’s assembly and installation, which unfolded over several weeks this spring, ultimately were integrated into infrastructure improvements planned as part of the MVR renovations. That facilitated some enhancements, such as improved lighting and drainage and a snow-melt system, which will preserve winter access to its walkways without potentially damaging shoveling or salt.

“I think we’ve paid the right respect to it in terms of the infrastructure and the integration,” said Kristine Mahoney, director of facilities and operations at CHE. “While this is very personal to the College of Human Ecology, we really wanted it to be a piece of art for the entire campus.”

A large team helped create PolyForm and its prototypes over a period of years, including several AAP students and alumni. They include: Dillon Pranger, M.Arch ’14, the project manager and a senior designer at Jenny Sabin Studio; and Jordan Berta, M.Arch ’16; Charles Cupples, M.Arch ’15; Madeleine Eggers, B.Arch ’19; Charisse Tsien Mei Foo, B.Arch ’18; and David Rosenwasser, B.Arch ’18. Engineering design support was provided by Clayton Binkley, Lucas Whitesell, and Arup.

Walking through PolyForm for the first time recently, Obendorf declared the work “beyond expectations” and marveled at its constantly changing features.

“It’s never the same,” Obendorf said. “Just like human life.”

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe