This warehouse has placed an excessive number of traps – small grey boxes – in an area that lacks the darkness, food and protection that attract rodents. The study recommends placing fewer, more strategically placed traps.

To better protect food, place rodent traps near warmth, shelter

By Krisy Gashler

Rodent traps are more effective when placed near attractive features such as warmth and shelter – and sometimes using fewer traps in total can help food manufacturers and pest managers better protect food supplies and save money, a new Cornell-led study has found.

Rodents cause billions of dollars in losses to the food supply each year, and carry pathogens that can sicken and kill humans, including salmonella, E. coli and Leptospira. In the 1940s and 50s, scientists estimated that mice will only travel 20 to 40 feet from their nest sites to feeding sites, so they recommended that farmers, food manufacturers and distributors evenly space rodent traps or bait boxes in their facilities.

But in fact, placing traps or bait boxes based on rat and mouse behavior is more effective, according to the article, “Assessment of Factors Influencing Visitation to Rodent Management Devices at Food Distribution Centers,” which published June 12 in the Journal of Stored Products Research.

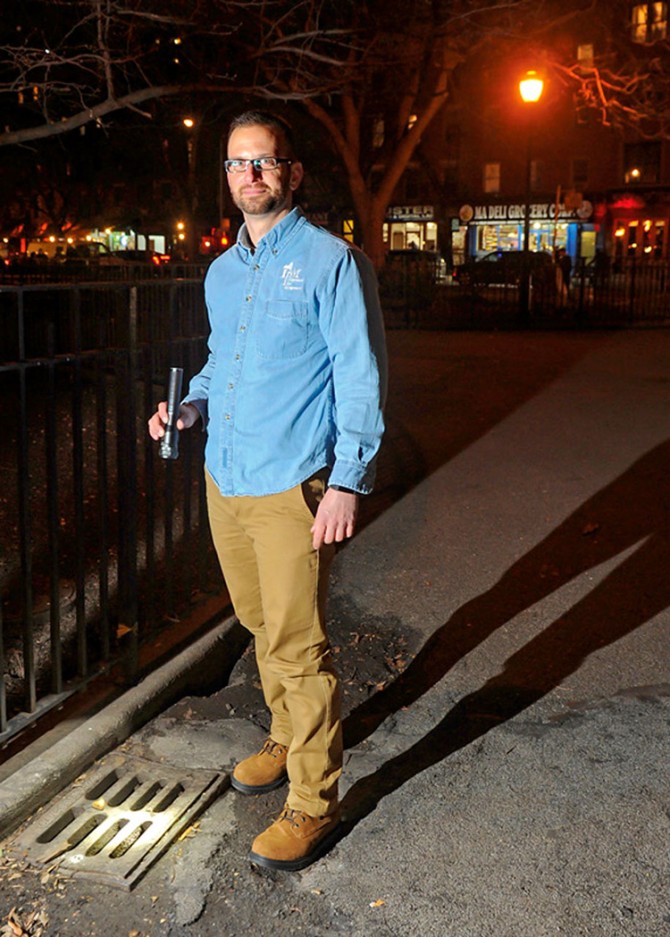

“From there, it just became a mantra without anybody scientifically evaluating it to see whether this was working,” said first author Matt Frye, community extension educator with the New York State Integrated Pest Management Program (NYSIPM) based at Cornell. “For a long time, inspectors would actually bring tape measures with them and measure the distance between devices. If it was different from the guidelines, the facilities would get penalized. The yardstick approach makes it very easy for facilities and auditors to implement programs, but it doesn’t really lead to effective pest management.”

In the new study, Frye, Jody Gangloff-Kaufmann, senior extension associate at NYSIPM, and three co-authors who work in or consult for the pest-management industry discovered that traps placed near areas with attractive features, like warmth and shelter, captured more rodents, while more than half of traps caught nothing.

In addition to smarter trap placements, the researchers also recommend fewer trap placements – a counterintuitive suggestion that pest control companies and food safety auditors may balk at – because both technicians and rodents can develop “device fatigue.” Rodents may avoid devices that have been in the same place for too long because they’re no longer interesting to explore. Technicians can be more effective if they’re spending more time inspecting, and less time simply checking traps.

“If you’re a technician and all you have time for is going from device to device looking for feeding activity or trap capture, you can’t spend time on inspection, and effective pest management is all about the inspection,” Frye said. “Pest managers should be looking for evidence of rodents, like droppings, and looking for areas where facilities are unintentionally making food, water and shelter available.”

For example, the researchers found that rodents seek warmth, and traps placed near heat sources caught more pests. The south and, especially, west sides of buildings, motors and refrigeration compressors all provide warmth and are attractive to pests, and should be a focus of pest management efforts.

Rodents also seek shelter to avoid predation, and were captured more often at corners and edges of buildings and near indoor spaces that are shadowed during the day. They also ate more bait near unmaintained outdoor vegetation. Effective pest managers should make recommendations about facility setup and sanitation to reduce potential rodent habitat, Frye said.

“In these facilities, there are racks upon racks of food being stored and sometimes the easiest way to store food on the bottom is to put things on pallets. Well, now you’ve made a cave: It’s dark, protected, with food right above them,” Frye said. “Once something like that becomes available for rodents to use as their home base, it’s very difficult to keep the population under control.”

Gangloff-Kaufmann said she hopes this work will help food suppliers to adopt the stricter standards of the Food Safety Modernization Act, which emphasizes preventing food contamination instead of just responding to it.

“In the battle against rodents, refining management based on pest behavior is fundamental,” she said. “This work could lead to a reduction in the use of rodenticides, while offering better rodent management and a safer food supply.”

The study covered rodent management at 12 facilities: seven in the metropolitan New York area (New York, New Jersey and Connecticut), and five in the greater Toronto area. Partnering with industry pest control companies, RK Environmental Services, LLC, and Abell Pest Control, and with prominent rodentologist and industry consultant Bobby Corrigan of RMC Pest Management Consulting, was critical to finding real-world facilities to study, Frye said.

The research was supported by a Hatch grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

Krisy Gashler is a writer for the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe