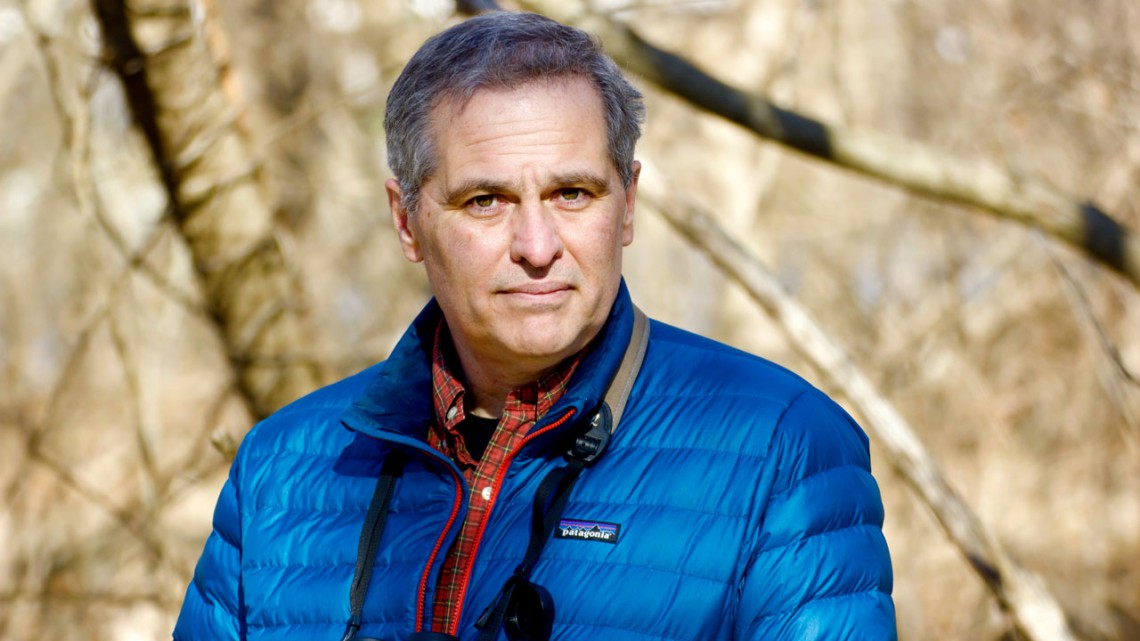

Evolutionary biologist Ian Owens envisions building broad coalitions that unite government, industry and an engaged public, and making sustainability the focus of his work as the new director of the Lab of Ornithology.

New Lab of Ornithology leader brings sustainability that unites

By Gustave Axelson

Ian Owens is taking the helm of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology at a critical moment.

Scientists at the Cornell Lab and elsewhere are sounding the warning bell that America’s birds are in crisis. In 2019 they published findings in the journal Science showing North America has lost more than 3 billion birds since 1970.

“Over the last 20 years, by building pioneering technology, citizen science and research programs, the Lab put itself in the position to show the decline in nature in a way that nobody else can do,” Owens says. “The clear challenge for the next 20 years, and the big priority from the moment I go into the office, is to figure out how we can change that loss curve. How do we improve the position for nature?”

Owens, who began at Cornell on July 1, brings 25 years of experience serving as a professor and departmental chair at Imperial College London, and as a director at both the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History and the Natural History Museum of London. He envisions building broad coalitions that unite politicians and government with business and industry and an engaged public, as he has in the past, and he plans on making sustainability the focus.

“It’s not a zero-sum game between the environment and humanity,” Owens says.

“You can’t expect humans to stop being innovative or to stop needing resources. So it’s harder than just protecting everything. It’s about protecting the most valuable parts, and then sustainably using the resources we need. And that’s where our research comes in, understanding the trade-offs and trying to figure out the best options. Because people want positive solutions for environmental sustainability.”

Perhaps one of the best examples of Owens’ way of thinking comes not from birds, but from rocks – and a public-private coalition he helped build at the Natural History Museum in London.

“We wanted to use the unique attributes of that amazing museum, the collection, the scientific expertise and the public audience to make as big an impact as we could on contemporary questions facing society,” Owens says.

During his time as the director of science at the London museum, he oversaw a research program that used the institution’s world-leading minerals collection to tackle the thorny question of how to source the scarce minerals needed for smartphones and electric car batteries.

“These kinds of minerals are becoming the new petroleum,” Owens says. “But they’re often not extracted sustainably.”

The London project showed how these critical elements could be extracted in a more environmentally friendly manner, using lower temperatures and pressures.

“The teams worked with a lot of companies to put the program together, and got funding from the U.K. and European governments, which realized that this was a key area for business and the future,” Owens says. Along the way, he says, government and industry became partners in telling a story about how to extract the scarce minerals needed for the future in the cleanest way possible.

Then Owens helped take that story to the public, he says, using “the most beautiful mineral specimens as a centerpiece of the London museum’s newly imagined Hintze Hall. It was like an art installation, but we were able to say that this rock here holds the future of future technologies.”

The kicker, he says, was seeing children dig into their pockets and marvel at where the lithium batteries in their smartphones had come from: “The kids were all over that. I mean, it was a great story for the public.”

Birds, Owens says, have even greater storytelling potential to inspire championing sustainable solutions. And ornithology is a subject Owens knows even more about: He’s an evolutionary biologist who has dedicated his research career to the behavior and ecology of birds and applying knowledge about species diversity to understanding extinction risk and conservation planning.

“With his very strong background in research, Ian has years of experience supporting research and then bringing it to the public forum,” says Linda Macaulay, chair of the board of directors at the Cornell Lab. “He will continue this drive to inform and effect awareness and sustainable change using the tools and outreach we have built at the Lab.”

Owens points to the Cornell Lab’s research and conservation partnerships with corporations,government agencies and nonprofit partners as examples of the kinds of sustainability initiatives he wants to grow. The Cornell Lab works with coffee farms in Central and South America on a biodiversity conservation initiative with Nespresso. And recently the Walmart Foundation awarded the Cornell Lab and the Cornell Atkinson Center for Sustainability a grant to study how the Lab’s extensive bird data can be used to better understand and monitor pollinator health.

“When both farmers and Fortune Global 500 executives are excited about working with the Cornell Lab and Cornell Atkinson to enhance the sustainability of global supply lines, that’s when you know you’re doing something worthwhile,” Owens says.

A key to doing even more with more partners will be deepening the Lab’s relationship with colleagues and teams across its home in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences (CALS) and elsewhere at Cornell.

“There’s a clear appetite and ambition for Cornell to make a real difference with respect to sustainable agriculture and natural systems,” Owens says. “I think we can work with partners across the university to figure out new ways to measure biodiversity in agricultural landscapes and identify practices that promote healthy ecosystems.”

Owens says he sees further potential for the Lab to work with researchers in other disciplines at Cornell on joint artificial intelligence initiatives, building off the Lab’s machine learning successes. They include innovating bird migration prediction models using weather radar, using machine learning to predict the prime nights for “lights out” initiatives in big cities to lessen building-collision risks for birds, and inventing computer-hearing technology that can identify birds by their songs using automated audio recorders or even a smartphone.

“Artificial intelligence is clearly a big priority for Cornell, and it’s a game-changing technology for the Lab of Ornithology, too,” Owens says.

Another immediate priority, Owens says, will be advancing diversity, equity and inclusion in the Lab’s culture and work, including diversity amongst its employees and the communities of people who interact with the Lab to enjoy, learn about, and protect birds and nature.

Because the Lab is fundamentally based on research and data, Owens says it can cut through politics and build a broad coalition for protecting and enhancing nature alongside human activities.

“Humanity has proven that we’re capable of achieving incredibly audacious goals,” Owens says. “Look at what’s happened in the last year with respect to COVID-19. We can do amazing things when we work together and harness human ingenuity.”

Owens has now taken the baton from his predecessor, John Fitzpatrick, who retired as the Lab’s director after 26 years of leadership. He’s excited by the challenge ahead.

“I believe that the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, with our science and our research and our technology and our storytelling, can be that force for using birds to build goodwill for nature, for ultimately bending that loss curve,” Owens says. “I know we can do it, and I can’t wait to get started.”

Gustave Axelson is editorial director at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Living Bird magazine.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe