Hand and footprint art dates to mid-Ice Age

By David Nutt

An international collaboration has identified what may be the oldest work of art, a sequence of hand and footprints discovered on the Tibetan Plateau. The prints date back to the middle of the Pleistocene era, between 169,000 and 226,000 years ago – three to four times older than the famed cave paintings in Indonesia, France and Spain.

To answer the question, “is it art?” the team turned to Thomas Urban, research scientist in the College of Arts and Sciences and with the Cornell Tree Ring Laboratory.

“The question is: What does this mean? How do we interpret these prints? They’re clearly not accidentally placed,” said Urban, a co-author of the paper, “Earliest Parietal Art: Hominin Hand and Foot Traces from the Middle Pleistocene of Tibet,” published Sept. 10 in Science Bulletin.

“There’s not a utilitarian explanation for these. So what are they?” Urban said. “My angle was, can we think of these as an artistic behavior, a creative behavior, something distinctly human. The interesting side of this is that it’s so early.”

The project was led by David Zhang of Guangzhou University in collaboration with researchers from Bournemouth University, Xi'an Jiaotong University, Education University of Hong Kong, Institute of Geology and University of Minnesota.

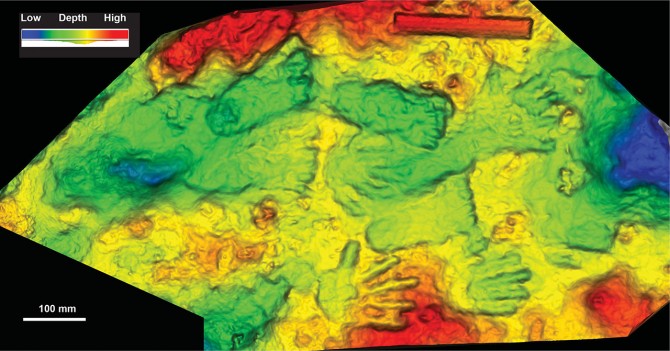

Urban’s involvement with the group grew out of his ongoing efforts to study human and animal footprints in the White Sands National Park in New Mexico as a way to understand the behaviors of human ancestors. One of Urban’s colleagues on that work, Matthew Bennett with Bournemouth University, was part of the initial team that examined the “art-panel” that was found on a rocky promontory at Quesang on the Tibetan Plateau in 2018. A series of five handprints and five symmetrical footprints were stamped in travertine, a freshwater limestone that was deposited by a nearby hot spring, then hardened over time.

“It would have been a slippery, sloped surface,” Urban said. “You wouldn’t really run across it. Somebody didn’t fall like that. So why create this arrangement of prints?”

The fact that the panel includes handprints gives one hint. While footprints are common in the human record, handprints are much rarer. Their presence connects the Tibetan panel to a tradition of parietal art – that is, art that is immobile – typified by hand stencilling on cave walls.

The oldest such art, found at the Indonesian island of Sulawesi and El Castillo cave in Spain, dates back between 40,000 and 45,000 years. In light of the Tibet discovery, the Chauvet cave paintings in France – approximately 30,000 years old – are practically contemporary.

Urban’s collaborators used uranium series dating to determine when the art-panel originated. They hypothesize the child who made the footprints was around 7 years old and the child who made the handprints was about 12.

More important than the age of the artists, however, is the question of their species. Were they Homo sapiens? An extinct hominin? One theory, supported by recent skeletal remains found on the plateau, holds they were Denisovans, a mysterious group that were ancient relatives of Neanderthals.

While their exact identities may never be known, the art-panel makes the case for the earliest hominin occupation on the Tibetan Plateau.

Equally difficult for the researchers to resolve is that perennial question, which no amount of uranium dating will ever settle: What constitutes art?

“These young kids saw this medium and intentionally altered it. We can only speculate beyond that,” Urban said. “This could be a kind of performance, a live show, like, somebody says, ‘hey, look at me, I’ve made my handprints over these footprints.’”

In this context, Urban argues for a broader definition of art, even if it makes some connoisseurs bristle.

“Different camps have specific definitions of art that prioritize various criteria,” he said. “But I would like to transcend that and say there can be limitations imposed by these strict categories that might inhibit us from thinking more broadly about creative behavior. I think we can make a solid case that this is not utilitarian behavior. There’s something playful, creative, possibly symbolic about this. This gets at a very fundamental question of what it actually means to be human.”

The research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and the Early Career Scheme of Research Grants Council of Hong Kong.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe