News directly from Cornell's colleges and centers

Lost in a thousand leaves with Luca Padroni

By Edith Fikes

Italian artist and long-time Cornell in Rome visiting critic Luca Padroni reflects on his depiction of the human condition in relation to time and the natural world.

In conversation with Isabel Padilla Bonelli (B.F.A. '23)

Luca Padroni, a contemporary Italian artist and longtime visiting critic at AAP's Cornell in Rome program, creates work that questions notions of time and space and reflects on the human condition in relationship to the natural environment through a changing lens of past, present, and future. Padroni's upbringing in Rome and long periods spent in a number of African countries inform both his recent investigation of the natural and animal world and the emotive, figurative compositions of urban landscapes he has largely created to now. Padroni has participated in many exhibitions both internationally and in Italy, and his work is included in several public collections including the Certosa di San Lorenzo, and the Capitoline Museums in Rome.

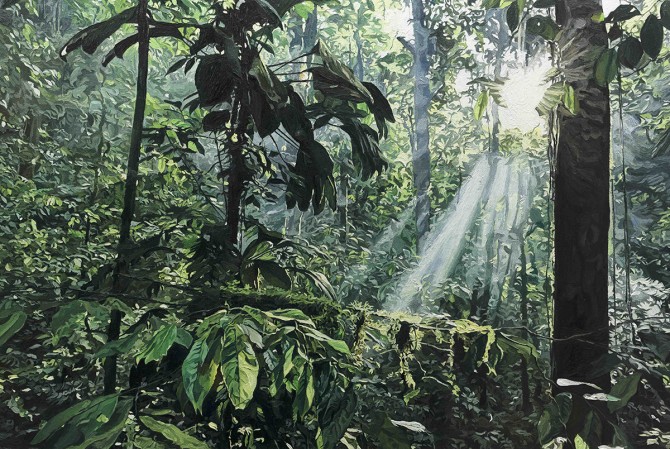

Padroni's current solo exhibition La Vita Continua (Life Continues) at Orto Botanico di Roma showcases the artist's depiction of a wild jungle domain and the mysterious beasts that inhabit it. Characterized by combinations of mediums ranging from charcoal, pastel, and watercolors to oils, the works on display employ a mixed-media approach in materiality and assemblage to create environments rich in movement, life, and contemplation. The presentation of different mediums plays well with the gallery's site within the botanical gardens of Sapienza Universita di Roma where "nature shows itself in its complexity and makes the viewer feel in a safe place." La Vita Continua displays an imagined reality in which Padroni places himself in the positions of his ancestors, depicting scenes of his environment from a place of wonder, fear, and honor. In a time where our natural world is in an ever-growing presence of danger, Padroni's latest works notably "pay respect to the greatness of nature."

These latest works represent a desire to return to the origin of painting when humans were not yet able to write, perhaps not even to speak, and took in their hands a piece of burnt wood or colored earth and sketched the image of some large animal, or a particularly exciting hunting scene on the walls of a cave. What instinct drove them to do this? Maybe they did it to pay homage to the spirit of a mighty mammoth, or as a good omen for the next hunt? To inspire bravery?

The year, characterized by the pandemic — with all the horror, pain, and difficulties — has raised a general reflection on our increasingly distant lifestyle from nature, its rules, and its presence. Thus, these canvases started getting filled with plants and animals, a world unfortunately increasingly distant from our daily life.

I began to think about early human instincts, and, what I would have drawn on the walls of my house if it had been an improvised refuge — if I didn't know what awaited me tomorrow. If I had no certainty. I realized that I wanted to leave something positive and good for me like I believe our ancestors did.

For this show, you decided to exhibit watercolor and oil paintings as well as pastel and charcoal drawings. There are works dating to 2019 that seem to have developed into beautiful large-scale oil paintings, for example, Resta con me Grande Spirito. How did these works evolve?

For La Vita Continua, I knew I wanted to create and include images that would have the same value or role in my life today as rupestrian paintings must have had for our ancestors thousands of years ago — images that would be functional to my life; accompanying my daily routine; paying respect to the greatness of nature; for good luck.

I started to make this work in September 2019 for a group exhibition, Abbi Cura Cabine d'Artista, curated by Paola Pallotta. Forty different artists were each given a cabinet of approximately 2.5 m x 3.5 m (approx. 8' x 11.5') and were free to do anything we wanted with the space. I thought of covering the entire surface of the interior walls with paper to create a life-size drawing. The cabinets were part of a seaside structure, we call them Stabilimenti Balneari, where people change their clothes, rent a sunbed, and so on. Thus, I confronted the problem of what to draw on the walls. This context was common yet interesting. It was natural and human. It was then that suddenly, I thought of the rupestrian paintings and understood what I wanted from my work; from the walls. It occurred to me that it could have the same value our ancestors gave to their cave drawings.

In terms of a specific medium, I had the freedom and opportunity to exhibit some of my drawings, which is rare for a painter. Perhaps for obvious reasons, it was important that they were rendered in charcoal — one of art's most primordial media. I should also add that the Orto Botanico is a place for conservation and the promotion of awareness of biodiversity and climate change. Selecting the work and evolving its function as a whole toward this mission was meaningful and fully satisfying.

Concerning your technique, what influences your collage-like painting style that we see in your previous works, such as Il Sognosogno del Cardinal De Merode? How do pieces like these typically develop through the layers of mediums you use to make a single composition?

The Cardinal de Merode was an ecclesiastic who lived during the 19th century and can be considered one of the first urban speculators of modern Rome. In fact, he dedicated himself so much to the business of adjusting the city to its new role of capital of Italy, that he was accused of neglecting his ecclesiastic duties. The street portrayed in the painting, via Nazionale, is one of those he helped make towards the end of the 19th century. I couldn't take my mind off the idea that he might have had exciting, visionary dreams of the way it could be one day (today), with traffic and clumsy tourists, and the life behind the walls he was aiming to build.

But also, as often happens in my paintings, other elements came to be part of the painting. Like the foreground figures embracing, that is from a movie by my wife, Fabiana Sargentini. The male figure is me. I appear at the end of the movie, never seen clearly in the face, to hug my fiancé. How does this fit into the painting? Difficult to say. Who knows what paths my mind takes when building up an image? Often, the collage paintings take a completely different direction from my initial intentions according to the fantasies a place suggests, the things I get to know about the history (Rome is very exciting from this point of view), my private life, the people I talk to there. I spend time in these areas, where the paintings are mainly set—drawing, taking pictures, and then elaborating on all of this as I paint in my studio.

Lastly — if you can be so honest, where does much of your inspiration come from at this moment?

Who knows? For now, I just enjoy feeling lost in a thousand leaves.

This story first appeared in the News section of the Architecture, Art, and Planning website.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe