News directly from Cornell's colleges and centers

Stories last longer than symbols

By Edith Fikes

With Who is Afraid of Natasha? Art Professor of the Practice Joanna Malinowska and collaborator C.T. Jasper bring a monument (back) to life.

By M Constantine

In its new location, Malinowska and Jasper's sculptural element of Who is Afraid of Natasha? illuminates the site of a former women's commune, a refuge for "XIII-century feminists" who were there afforded social and economic independence and a lay religious life without renouncing the world. Their version of Natasha is also marked by a red lightning bolt, calling into the space the contemporary struggles of the Strajk Kobiet movement in Poland, which actively fights for women's reproductive rights against reinvigorations of draconian abortion restrictions. Malinowska explains, "We were thinking that every nation has suffered some form of trauma throughout its history. For Poland, one of the traumatic periods was communism. For Belgians, it is currently coming to terms with the country's colonial past and the predatory politics of King Leopold II. Every nation has its demons."

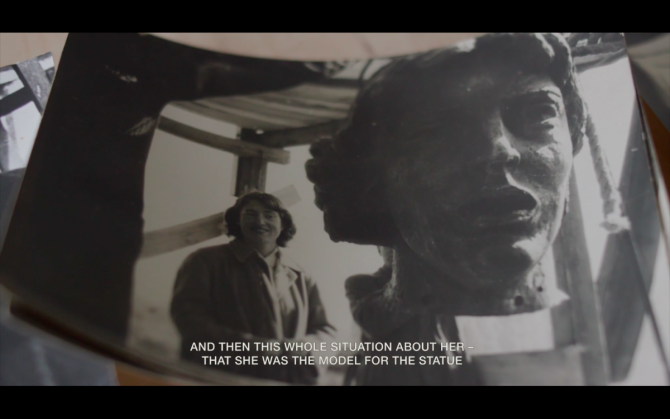

With the video that plays inside the Begijnhof, we learn that Natasha is, or always was, an allegory, and a part of many other stories. Viewers get a composite portrait of Natasha that includes narration from dozens of curators, historians, and residents of Gdynia. They are filmed in their homes, offices, and in public space, as the video highlights the more industrial corners of the city. These storytellers are all on the phone (a formal solution to pandemic conditions), which gives the effect of listening in on friends in conversation, catching up, and sharing their thoughts with each other — rather than an invisible someone behind the camera. Among these accounts, we learn that Natasha was part of a love story between the monument's creator, Marian Wnuk, and his lover, artist, and the model for the sculpture, Magdalena Więcek — who then went on to establish herself as a successful sculptor.

Malinowska herself recounts, "I didn't know about the removal until one day when, during my usual summer or winter visit to my home city, I went for a walk and saw that the statue was gone. I clearly remember the impression that something was missing; something was different. At first, I didn't know what — and then, I realized that Natasha was no longer standing in the middle of the square." According to Malinowska, it is possible for the original statue, its removal, as well as its reconstruction to be viewed together as a provocation to reopen and reexamine the past.

As Malinowska has articulated in her own reflections and revealed with the piece's inclusion of multiple accounts of life with and without Natasha in the square, trauma and ways of coping with it come in many forms. Symbolism can be left to interpretation. Stories suture lives and worlds. Bringing an interest in anthropology that has also influenced many of their previous collaborative works, Malinowska and Jasper highlight the social histories behind the monument. By re-siting and re-staging cultural fragments from one context to another, similar to their work for the Polish Pavilion at the 2015 Venice Biennale, Halka in Haiti, Malinowska and Jasper create juxtapositions that bring into stark relief the consequences of previous dislocations imposed by communism, capitalism, colonialism, and empire, among other present and historical forces. With Who is Afraid of Natasha? the artists ask yet another question: What if a monument did not have to be fixed relative to one point in history, or one place, but could instead come alive, be remade, and given new meaning?

This story first appeared in the News section of the Architecture, Art, and Planning website.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe