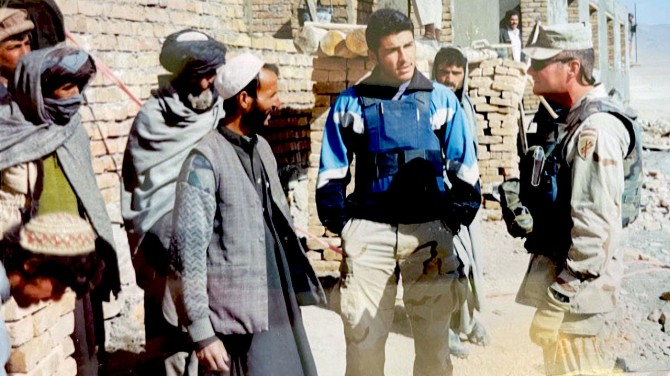

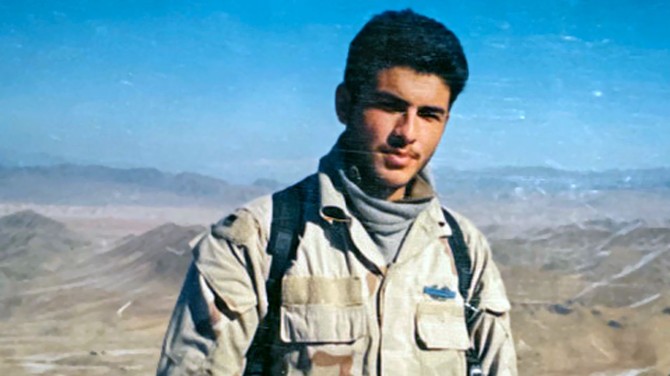

Farid Ferdows, who served as an Afghan interpreter for the U.S. Army, says Cornell welcomed him with academic support, financial aid and comradery with other veteran students.

Farid Ferdows ’21: ‘For those who dream, Cornell is your place’

By Linda Copman

Farid Ferdows ’21 was not expecting to do well at Cornell. The 35-year-old freshman and U.S. Army veteran had served as an interpreter in Afghanistan for more than a decade. He was worried about fitting in with peers who were half his age and his “less than stellar” academic preparation under Taliban rule in Afghanistan. He was intimidated by his fellow students, fearing they would be competitive. Ferdows had 50% confidence that he would make it even through his first semester.

“Honestly, looking at myself and seeing an Afghan high school student who was practically illiterate when he graduated, I would not be my first, second or even 10th pick for admission here,” Ferdows says. “For Cornell to take that chance on me – that speaks volumes about the ethos that Cornell lives by.”

He did not anticipate the robust support system he discovered at Cornell. Ferdows found kinship with the other veteran students in the Cornell Undergraduate Veterans Association. And he received ongoing academic support in writing, tutoring and study skills through the John S. Knight Writing Institute, the Office of Academic Diversity Initiatives, which assists first-generation students, and other programs.

“To my surprise, I found Cornell to be the most welcoming place,” he says. “I didn’t feel that I didn’t fit in – in fact, I fit in from every angle. After the first semester, I realized I wasn’t going to fail, I was going to excel here.”

Faith in education

Ferdows was born in 1983, during the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, the eldest of six children. His parents grew up in the countryside near Kabul, in Logar province, and later moved to Kabul, where his father worked for an arm of the government that provides services to war victims. Ferdows says his family was relatively comfortable and Kabul was peaceful and prosperous.

When Ferdows was in fourth grade, the collapse of the Soviet-backed government led to civil war. The wealthy fled the country while families like the Ferdows, who did not have the means to leave, fled the fighting – losing their jobs and homes.

Ferdows’s family returned to their small parcel of land in Logar, where they grew wheat, corn and potatoes to sustain themselves. His father did manual labor and Ferdows and his brothers helped in the fields. “Those left behind [who couldn’t afford to leave Afghanistan] were poverty stricken,” Ferdow says. “We lived on basics – potatoes, flour, corn, and cooking oil – and that’s what people still live on.”

They and many Afghan families viewed education as the only means of upward social mobility for their sons; daughters did not attend school at that time. Ferdows and his brother Shabir Ferdows ’13 resumed their education at a regional school, walking or biking two hours each way.

“It really wasn’t school in the conventional sense,” Ferdows recalls. “There were no classrooms, so we sat under a tree. When the leaves fell, we were sent home for the season.”

The force behind him

When the Taliban took control of the government in 1996, the civil war ended and Ferdows’s family moved back to Kabul so his father could seek employment. After unsuccessful attempts to launch a household items resale business and a firewood business, the family’s savings were exhausted. And education was no longer a path to stability. “The quality of schools evaporated under the Taliban,” Ferdows says. “The emphasis was on religious subjects, and most of traditional teachers, who were women, were forced to go home.”

Ferdows’s uncle, Mirza Gul Yawar, a professor of psychology and English at Kabul University, began offering classes for the children of local shopkeepers. “My uncle made me his main focus, with the goal to make sure I was proficient in English.” Yawar coached Ferdows one-on-one over the next two years and arranged private English lessons. “I took virtually all the English classes that were offered,” Ferdows says.

The family was hoping Ferdows would go to college and study medicine, and his exam scores qualified him to choose this path.

But his life soon took a different direction.

Hope arrives in uniforms

When he graduated from high school in 2000, Ferdows decided to take a gap year before attending college. Then came 9/11.

Instead of being terrified of the U.S. invasion they knew would follow, he and his fellow citizens were hopeful. “They saw international involvement in the country as a chance to escape the absolute poverty and devastation the Taliban had caused,” Ferdows says.

Ferdows speaks two Afghan languages, Dari and Pashto, and was soon hired as an interpreter for the coalition troops. His first assignment was helping a British unit conduct an inventory of humanitarian aid organizations operating in the country. Ferdows earned $550 per month, which he describes as a “huge amount” – enough to raise his entire family’s standard of living within a few months.

Ferdows’s second assignment was for a U.S. Army Reserve unit from Webster, New York, led by Chief Warrant Officer Tim Mueller. “From day one, Tim adopted me as his son,” Ferdows says. A few of the Americans in his unit were the same age as Ferdows, and they invited him to play video games and watch TV – a luxury he hadn’t enjoyed for nearly a decade. When asked to remain on base 24/7 to translate, he gladly accepted.

He loved his unit’s work: surveying infrastructure in need of reconstruction, such as schools, clinics and dams. “We went to the same sort of schools that I had attended, that now lay in ruins,” Ferdows says. “We had the opportunity to rebuild 37 of them.”

With Mueller’s academic and financial help, Ferdows eventually got a visa to move to Rochester, New York, in 2004, to begin his studies at Monroe Community College (MCC).

Finding his footing

Ferdows’s high school education did not prepare him for academic success at college. When he entered MCC, he had to build his basic math and academic writing skills. Thanks to the Mueller family, Ferdows’s brother Shabir followed the same path a few years later, obtaining a visa and living with the Muellers during his studies at MCC.

“We started out illiterate,” Ferdows says. “We both attended MCC, where we took a non-credit math class to teach us basic addition, subtraction, multiplication and division.” Ferdows credits MCC’s outstanding advisors and academic support system for helping him graduate in 2007 with a 3.74 GPA.

Inspired by Mueller, Ferdows joined the U.S. Army Reserves after he graduated from MCC. He was deployed to Afghanistan in 2008, where he spent the next eight years . He is especially proud of his service as personal interpreter to U.S. Navy Admiral William McRaven, providing translation and cultural insights during McRaven’s interactions with senior-level Afghan officials. He earned a Bronze Star medal for this service in 2009.

Hitting his stride

In 2016, at age 34, Ferdows decided to pursue a degree in political science, a topic he had become passionate about during his military service. After graduating from MCC, his brother Shabir was admitted to Cornell and graduated in 2013. “Shabir spoke so highly of Cornell in every sense, from the robust academic curriculum to the generous financial assistance he received,” Ferdows says. “My brother basically told me not to apply anywhere else.”

Ferdows scanned the course registers and was excited by the breadth of political science courses Cornell offered. He applied to the College of Arts and Sciences and was admitted in 2017. He deferred his acceptance for a year to finish his work with the Army in Afghanistan, and started at Cornell in 2018.

Ferdows double majored in Near Eastern studies and government, graduating in 2021 with a 3.993 GPA. “This is not a testament to my hard work,” he says. “It was the environment and the support from my professors that made this possible.”

He is also immensely grateful to Cornell for the financial assistance covering all of his expenses. “Because of Cornell’s generosity, I never worried that I wouldn’t be able to make it,” he says.

Ferdows is now preparing for the LSAT exam. He aspires to study human rights law and work for an international organization like Amnesty International or Human Rights Watch. “I hope to work on issues of human rights in Afghanistan,” he says. “What I witnessed growing up has made me want to do what I can to make a difference.”

Bringing the family home

Since the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan in August, Ferdows has worked with his former professor Steve Israel, professor of practice in the Department of Government and director of Cornell’s Institute of Politics and Global Affairs, McRaven and several New York elected officials to evacuate his mother, father and sister from Kabul. His family arrived safely in the U.S. via the United Arab Emirates in September.

“The two weeks from the fall of Kabul until I got them out were the hardest weeks of my life,” Ferdows says. He is looking forward to bringing them to Ithaca.

Ferdows says his gratitude for Cornell is “beyond words.” He thanks Robert Hutchens, professor of economics in the ILR School, who is helping his brother Shafi prepare for the GED exam. He also thanks his family. “I’m kind of embarrassed to admit that my family was right,” he says. “If it weren’t for their focus on education, I wouldn’t be where I am today.”

Linda Copman is a writer for Alumni Affairs and Development.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe