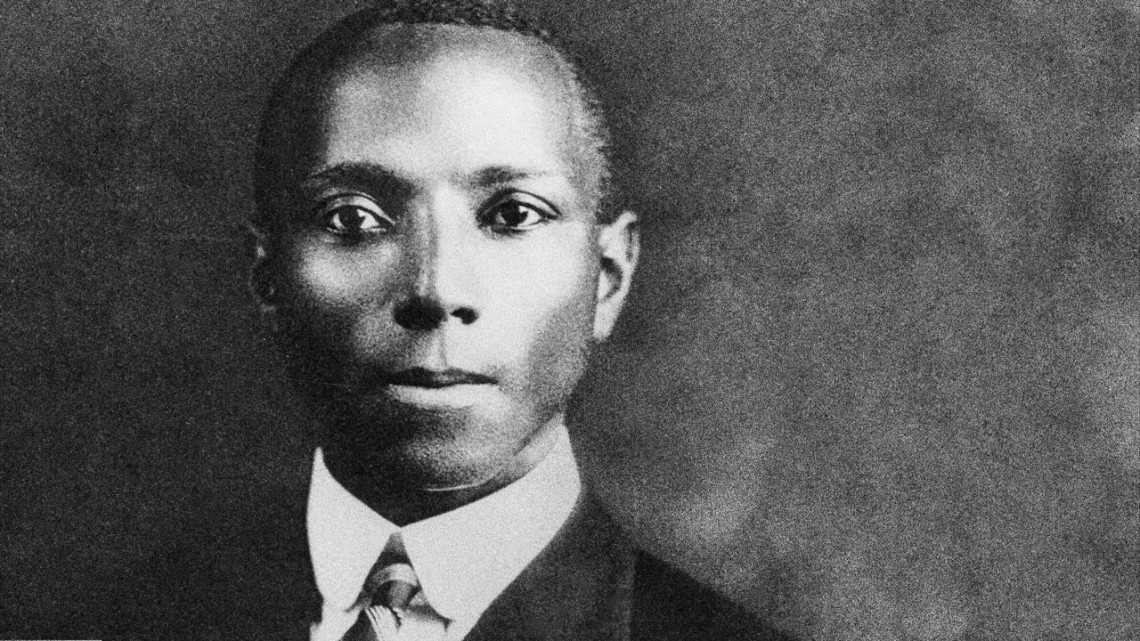

Thomas Wyatt Turner, Ph.D. 1921, shown here in his 1901 graduation photo from Howard University, was the first Black person at Cornell to earn a doctorate and the first Black person in the nation to earn a doctorate in botany.

Fellowship honors Cornell’s first Black doctorate, Ph.D. 1921

By Susan Kelley

At age 18, Thomas Wyatt Turner, the son of formerly enslaved sharecroppers, walked 50 miles from his Maryland home to start his undergrad career at Howard University.

That determination, demonstrated throughout his life, catapulted Turner in 1921 to become first Black person at Cornell to earn a doctorate and the first Black person in the nation to earn a doctorate in botany. A pioneer in the civil rights movement, he helped found the NAACP and was a long-time advocate of equity and inclusion for Blacks in the Roman Catholic Church.

In honor of Turner’s achievements, Cornell has created the Thomas Wyatt Turner Fellowship, which aims to increase the number of graduate students from historically underrepresented backgrounds doing research in inclusive and sustainable agricultural development.

“For me, my color was my earliest handicap. Doors would be closed, opportunities lacking, barriers erected because I was black,” Turner wrote in his memoir, “From Sharecropper to Scientist.”

“The American dream would be a dream only – to become a train engineer, a wealthy farmer, a storekeeper or whatever. But if I just had a chance, I would exert every effort to push open the door, tear down the barriers, seek every opportunity to become a man with dignity, respected for my personal worth.”

The fellowship is housed in the Department of Global Development in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences (CALS) through its Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Crop Improvement. The fellowship supports graduate students enrolled at 1890 land-grant universities, which are historically Black colleges and universities. Fellows will attend Cornell for 10 months, doing research and studying with faculty mentors at Cornell and their home institutions. Applications are being accepted through March 1.

“It is important to think about how we can shape agricultural research for the future: disrupting business as usual and rethinking our priorities,” said Hale Ann Tufan, research professor of global development in CALS with a joint appointment in the School of Integrative Plant Science (SIPS) in CALS. “Diverse teams and institutions are more innovative, effective, equitable and impactful, which should all be core values in agricultural research.”

Turner was born in 1877 in Maryland, the fifth of nine children born to Eli and Linnie Turner. His quick mind earned him the nickname “Lawyer” at Charlotte Hall, the Episcopal high school he attended. At Howard, he worked his way through school, tending furnaces for $1 a week and carrying shopping baskets for white women at the market. He graduated in 1901 with a bachelor of arts degree.

He began graduate work at Catholic University but had run out of money when Booker T. Washington recruited him to teach at Tuskegee Institute. He earned a master’s degree from Howard in 1905, becoming an expert in plant nutrition and disease, ecology, soil science, tree surgery and cotton breeding. Two years later, he married Laura Miller. He was a professor of applied biology at Howard from 1913-24 and acting dean of the school of education there for a decade.

He took leaves of absence from Howard in the summers 1915-17, and a sabbatical year 1920-21, to complete his dissertation at Cornell. It was based on his work for the U.S. Department of Agriculture researching the effects of fertilizer on potatoes in Presque Isle, Maine.

At Cornell, he worked with the world-renowned plant physiologist Otis Freeman Curtis to complete his dissertation, “The Physiological Effects of Salts in Altering the Ratio of Top to Root Growth.” The topic is still relevant today, said Edward Cobb, retired research support specialist at SIPS, who researched and wrote a blog about Turner’s accomplishments. “So many factors are important to understanding this topic. They include the type and method of fertilization, the type of soil, and the local environmental conditions, such as rainfall. It’s all tied together.”

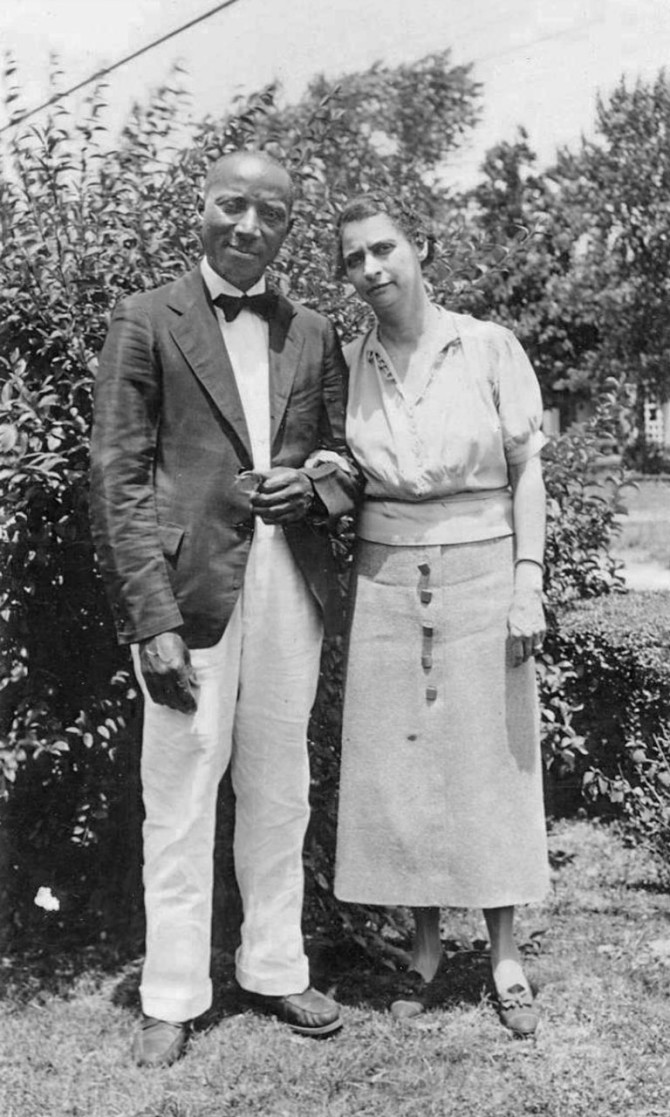

Turner went on to head the department of natural science at Hampton Institute in Virginia from 1924-45. During that period, his wife, Laura, died in 1934. Two years later, he married Louise Wright, a schoolteacher; they honeymooned in Ithaca. From 1949 to 1950, he helped Texas Southern University organize its biology department and was a professor of biology there until glaucoma forced him to retire.

“Turner was able to navigate through difficult circumstances to achieve his life goals,” Cobb said. “He didn’t give up on his life or the lives of others.”

Throughout his career, he was a strong advocate of equal opportunity and inclusion. He was a founding member of the NAACP as the first secretary of the Baltimore branch in 1910; in 1915, he chaired the NAACP’s citywide membership drive in Washington, D.C. He also advocated for the rights of Black people in the Catholic church, which at that time allowed segregation in its congregations. In 1917, he founded the Committee Against the Extension of Race Prejudice in the Church, which later became the Federated Colored Catholics of the U.S. He was its president for many years.

“I was one of the first Black people to do a lot of things,” Turner said in a 1977 interview. “I didn’t get up and start cussing people out. But I said things.”

At a meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Kansas City, he was told at a hotel he had to take the freight elevator because he was Black. “I am not freight,” he replied, and was allowed to take the passenger elevator.

After retirement, he lived in Washington, D.C., with a niece, Lois Broadus, who said he loved opera, including “Porgy and Bess” and “Carmen.” He died in 1978 at age 101; obituaries appeared in The Washington Post and The New York Times.

The Turner Fellowship is a gateway to building long-term, equitable institutional relationships with 1890 land-grant universities, Tufan said. “By building these mutually beneficial relationships on a foundation of trust,” she said, “we envision regular student and faculty exchanges between Cornell and partner 1890 institutions that yield novel and impactful areas of research and scholarship.”

Kelly Merchán, communications specialist in the Department of Global Development, contributed to this article.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe