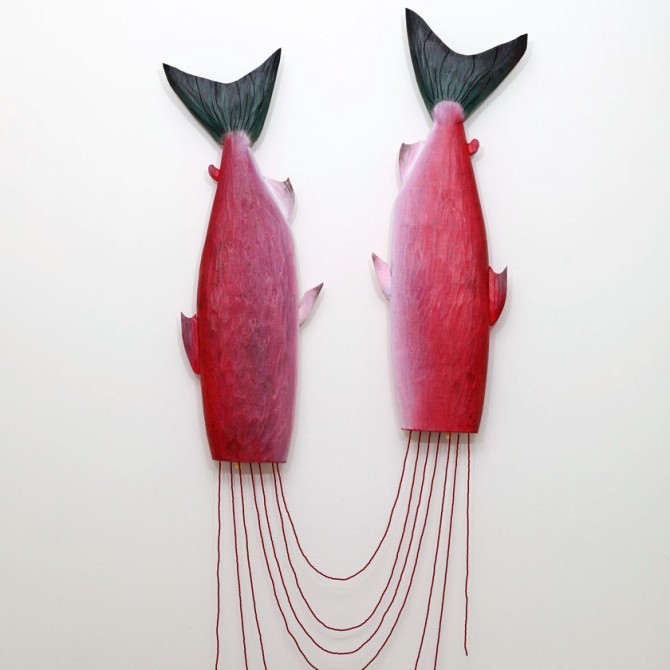

Artist Henry Payer’s piece “& of the Line, 2017” is featured in a new exhibition opening Dec. 15 at K Art in Buffalo, New York. It is mixed media and collage on Army wool.

Alum brings contemporary Indigenous art into the mainstream

By Linda Copman

David Kimelberg, J.D. ’98, has always been a fan and collector of contemporary Indigenous art. An active member of the Seneca Nation, Kimelberg and his brother, artist Michael Kimelberg, had dreamed of someday opening a gallery to showcase this art.

At the time, only a handful of contemporary Indigenous artists had achieved national recognition. And there was no gallery specifically featuring their work.

“The many very talented contemporary Indigenous artists just weren’t getting the recognition they deserved,” says Kimelberg, who lives on Seneca territories, 40 miles southwest of Buffalo, New York. “We wanted to change that.”

In December 2018, Michael Kimelberg died unexpectedly, from an undiagnosed congenital heart defect. His death motivated Kimelberg to bring their dream to fruition, he says. “I thought, you know what, if we’re not going do it now, we’re never going do it.”

In 2019, Kimelberg bought a three-story brownstone in downtown Buffalo. A year later, he launched K Art, an art gallery featuring the work of contemporary Indigenous artists from New York state and across the continental U.S., Alaska, Canada, Mexico and Australia.

A new exhibition of work by two artists – “The Cadence of Night” by Duane Slick, a member of the Meskwaki and Ho-Chunk nations, and “La Garnison Mentalité” by Henry Payer, a member of the Ho-Chunk Nation – opens Dec. 15 and runs through Feb. 23, 2023.

The gallery also represents artists including G. Peter Jemison, a member of the Seneca Nation, Heron Clan. His work has been acquired by influential institutions including The Modern Museum of Art (MOMA) and the Whitney Museum of Modern Art. Known for his naturalistic paintings and series of works done on brown paper bags, Jemison makes art that embodies “Orenda,” the traditional Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) belief that every living thing and part of creation contains a spiritual force.

The gallery has also had success in the greater art world. It presented a booth at Art Basel Miami Beach, one of the most important art fairs in the U.S, Dec. 7-9. “It was a real honor to be there, and the reception has been fantastic,” Kimelberg says. “Ours was named a top-10 booth by ARTnews for Art Basel Miami Beach, and also for our booth at The Armory Show in New York City earlier in the year.”

Supporting artists and the Seneca Nation

Kimelberg recalls the naysayers – and there were many – who warned him that the gallery would never succeed. They said powerful gatekeepers in the art world would make access to artists and collectors difficult.

His experience has defied these dire predictions. For K Art’s first show, his team reached out to 10 of the top contemporary Indigenous artists to see if they would like to be included.

“They were all incredibly excited to be working with us and ready to give us their work. That’s pretty unheard of,” he says. “And, on the collector side, we have major museums that really want to work with us and that have made it easy for us. What I’ve learned is that the art world actually can be a pretty cool place.”

Kimelberg and his team connect with artists via word of mouth and by searching keywords in social media channels like Instagram. He and his gallery manager have found four young artists in this way; when the team sees artwork they like on Instagram, they contact the artist to arrange a Zoom call and discuss which works they would like to include in a show.

“We’ll give them a lot of advice, and we’ll support them, too. For some really young artists, we’ll pay them a certain amount every month to live on. It’s not a huge amount, but it allows them to focus on their art,” Kimelberg says.

He has also found ways to support the Seneca Nation – a family tradition. His mother, art teacher Pamela Ahrens, launched the Head Start program in the Seneca territories. His great uncle served four terms as president of the Seneca Nation during the 1950s and 1960s.

As a corporate attorney with a background in finance, Kimelberg lived and worked in Boston and New York City, before moving back to the Seneca territories with his family about 15 years ago.

His goal in returning home was to spearhead an economic development program for the nation. He founded Seneca Holdings, an investment company intentionally diversified from the gaming industry, to generate income for the benefit of the Seneca people.

Profits from Seneca Holdings have allowed the nation to install fiber optic internet in one of its communities of about 3,000 residents, including many school-aged children. “About five years ago, we pulled fiber through the whole territory,” Kimelberg says. “So, now, everyone has high-speed Internet, which has been a real gamechanger.”

Kimelberg doesn’t expect to make a living from the art gallery. He says the success he’s had in his legal and business career is allowing him to fulfill his dream of bringing contemporary Indigenous art into the mainstream.

A few of the artists have catapulted into the national spotlight, and their works have been acquired by important institutions.

He shares the story of one who worked other jobs his whole life to support himself as an artist. “His star has really risen over the past two years. Collectors are clamoring for his work,” Kimelberg says. “This is his full-time job now, and he has different problems, like, ‘How do I manage all this money coming in?’”

To him, success is changing other people’s lives for the better – helping to give them opportunities where they can learn and thrive, he says.

“I view my job as giving our artists all of the resources they need to grow and be successful,” Kimelberg says. “For them, success is having their work seen, talked about and ultimately acquired.”

This article is adapted from the original, written by Linda Copman ’83, a writer for Alumni Affairs and Development.

Media Contact

Abby Kozlowski

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe