Experimental vaccines offer long-term protection against severe COVID

In 2021, a group of scientists led by researchers at the University of North Carolina, Weill Cornell Medicine and NewYork-Presbyterian reported that the Moderna mRNA vaccine and a protein-based vaccine candidate containing a substance that enhances immune responses, known as an adjuvant, elicited durable neutralizing antibody responses to the virus that causes COVID-19 during infancy in preclinical research.

Now a follow-up study by the same group, published Dec. 1 in Science Translational Medicine, has found that the two-dose vaccines still provide protection against lung disease in rhesus macaques a year after they had been vaccinated as infants.

The co-senior authors of the paper are Kristina De Paris, professor of microbiology and immunology at the UNC School of Medicine; Dr. Sallie Permar, chair of the Department of Pediatrics at Weill Cornell Medicine; and Dr. Koen K.A. Van Rompay, leader of the Infectious Disease Unit at the California National Primate Research at the University of California, Davis.

To evaluate infant vaccinations for the SARS-CoV-2 virus, the researchers immunized two groups of eight infant rhesus macaques at the California National Primate Research Center at 2 months of age and again four weeks later. Each animal received one of two vaccine types: a preclinical version of the Moderna mRNA vaccine or a vaccine combining a protein developed by the Vaccine Research Center of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), part of the National Institutes of Health, with a potent adjuvant formulation.

Consisting of 3M’s molecular adjuvant 3M-052 formulated in a squalene emulsion by the Access to Advanced Health Institute, the adjuvant formulation stimulates immune responses by engaging receptors on immune cells.

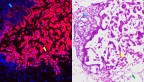

“Following up on our SARS-CoV-2 infant rhesus macaque study, we gave the animals a high-dose challenge with a SARS-CoV-2 variant one year later to assess durability of vaccine-induced immune responses and their efficacy,” De Paris said. “We found that both vaccines protected against lung disease, despite the fact that the challenge SARS-CoV-2 variants acquired numerous mutations in their spike protein that differed from the vaccine immunogen.”

Overall, the adjuvanted protein vaccine candidate maintained higher levels of neutralizing antibodies and provided superior protection compared to the mRNA vaccine, De Paris said. These data imply that these vaccines are safe and highly effective when given to young infant macaques. Furthermore, the results inform the optimization and development of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in a way that may reduce the need for frequent boosters and protect special populations that don’t have fully developed immune systems, such as children.

“With COVID-19, young infants are one of the most vulnerable pediatric populations. This fall, we are seeing a sharp rise in hospitalizations due to respiratory virus disease in infants as the result of a confluence of SARS-CoV-2, flu, and RSV circulation,” said Permar, the Nancy C. Paduano Professor in Pediatrics at Weill Cornell Medicine and pediatrician-in-chief at NewYork-Presbyterian Komansky Children’s Hospital. “We should take every opportunity to provide safe and effective vaccine immunity to our youngest patients, including considering COVID-19 vaccination earlier than the currently recommended 6 months of age.”

The paper’s co-first authors are Emma C. Milligan at the Children’s Research Institute in the UNC School of Medicine and Katherine Olstad at the California National Primate Research Center.

This research was funded through grants from the National Institutes of Health.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe