‘Cheap thrills’: Low-cost leisure leads to less work, more play

By James Dean, Cornell Chronicle

People today work substantially less than they did generations ago – not just because they have more money, but because of the virtually unlimited trove of cheap entertainment increasingly at their fingertips, according to new research co-authored by a Cornell economist.

From movies streamed on high-definition TVs to games played on smart phones, the researchers find that rapidly falling recreation prices over more than a century have been an important driver of why people in wealthier countries work fewer hours.

More recently, they suggest, diverging prices for specific types of leisure help explain a puzzle about why work hours have declined more among lower-skilled than higher-skilled U.S. workers, a gap referred to as leisure inequality.

“We have PlayStations, fantastic TVs, Netflix – a lot of really cheap leisure,” said Mathieu Taschereau-Dumouchel, assistant professor of economics and Robert Jain Faculty Fellow in College of Arts and Sciences. “It may be more tempting not to work, to stay home and play video games or watch a show, and we think these incentives matter.”

Taschereau-Dumouchel is a co-author with Alexandr Kopytov, assistant professor of finance at the University of Hong Kong; and Nikolai Roussanov, professor of finance at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School and research associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research, of “Cheap Thrills: The Price of Leisure and the Global Decline in Work Hours,” published April 12 in the inaugural issue of the Journal of Political Economy Macroeconomics.

The authors analyzed data from the U.S. and more than 40 members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) to evaluate the importance of recreation prices to declining work hours since 1900.

Americans then worked 50% more – 3,000 hours per year, on average, compared to 2,000 today. Economists generally attribute that drop to the “income effect” of rising wages, which have enabled richer households to choose more leisure time.

But over the same period, the scholars note, U.S. prices for recreation goods and services dropped by more than half, adjusting for inflation. For example, the price of a TV has fallen 1,000-fold since the 1950s; computers are 50 times cheaper than in the mid-1990s; and the cost of admission to a silent film in 1919 is about the same as one month of a streaming service offering a vast selection of movies and shows.

The researchers confirmed the same trends – falling work hours and recreation prices – in most OECD countries.

To assess recreation prices’ influence on work hours, the team applied a standard macroeconomic framework for studying long-term trends, with one important difference. They assumed balanced growth over time in various prices and quantities but, unlike most such models, allowed work hours to decline.

The analysis showed that rapidly falling recreation prices explain “a large fraction” of the decline in work hours, estimating them to be about one-third as important as the income effect of wages.

“We know that high wages can push people to work less, but it’s not the only thing that matters,” Taschereau-Dumouchel said. “Recreation goods and services becoming cheaper is also a big part of the story.”

The authors next investigated growing “leisure inequality” in the U.S. in recent decades, which seems to be at odds with wage data, Taschereau-Dumouchel said.

Since 1985, more educated workers (at least a college degree) have earned significantly higher wages, suggesting they could work less – but they have worked more. Meanwhile, less educated (high school diploma or less) workers’ wages have remained flat in real terms, suggesting they should work similar hours – but they are working much less.

“That was a bit of a puzzle,” Taschereau-Dumouchel said. “We thought the leisure price story could help us understand what’s going on.”

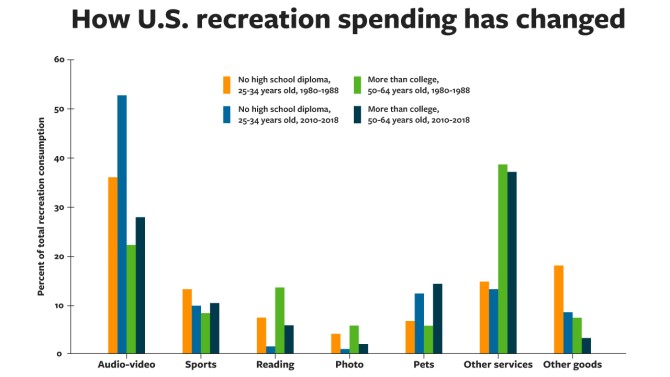

The researchers’ analysis of census data showed the two demographic groups consume different types of recreation whose costs have evolved differently. Younger, less educated households spend disproportionately on audio/video recreation items whose prices have plummeted. Older, more educated households spend more on recreation services – including performances, sporting events, club memberships and lesson fees – whose costs have increased about 20% because they are more labor-intensive.

For the less skilled, the researchers suggest, leisure has effectively become more attractive as the kind they primarily consume has gotten cheaper. In contrast, for more educated workers, higher wages and recreation costs may be offsetting, keeping their leisure time stable.

If historical trends continue, the authors speculate, one possible consequence could be a slowing down of the development of a more skilled workforce, if young people, in particular, choose TV and video games over school and work.

“If you want to think about how much people work over the long run, you need to think about the price of recreation,” Taschereau-Dumouchel said. “It’s an important driver of work hours.”

Media Contact

Adam Allington

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe