Fred Lee was facing difficult times running his family’s Long Island farm. A call to New York FarmNet, and its free, confidential consultants, helped get him and the farm back on track.

New York FarmNet cultivates stability for farming families

By Susan Kelley, Cornell Chronicle

In 2004, Fred Lee saw no other option but to sell off half his farm equipment – trucks, pipe, tractors, cultivators – an event that usually signals a farm is about to collapse. “Most farms, when they experience an auction, it means the end of the business,” says Lee.

He and his then-wife couldn’t afford the lease payments for most of the 142 acres of land they farmed in Peconic, Long Island, where they grew Chinese cabbage, bok choi and other Asian vegetables wholesale for New York City restaurants. At the same time, fierce competition had tanked their markets.

“I was really sort of at wit’s end,” says Lee, who grew up working on the family farm with his father and uncles, leveraging Long Island’s famous loamy soil and temperate climate. “I had to figure out, with what we had left, was it enough to keep going?”

He called New York FarmNet. The free, confidential Cornell program provides farmers with two consultants, one specializing in ag finances, the other in the social and emotional dynamics of running a family farm. Cornell is the only land-grant university in the U.S. to offer the service.

The FarmNet consultants visited the farm, listened to the Lees, brainstormed solutions and suggested a plan of action.

“It was very instrumental,” Lee says. “They said, ‘You need X amount to really cover your expenses and move forward.’ And so I focused on that number.”

The Lees pivoted. They began selling directly to local customers by starting up a C.S.A. (community supported agriculture), an unusual model at the time. “While we didn’t earn exactly the number that they had suggested,” Lee says, “it was the beginning of opening the door to see the light at the end of the hallway.”

Almost 20 years later, Sang Lee Farms is thriving. Lee and his family now grow more than 100 varieties of fruits, vegetables and herbs on about 100 acres, specializing in heirloom tomatoes, and orange and yellow seedless watermelon. They sell their harvest at their retail store, two farmers markets and to 650 C.S.A. members from Southampton to Queens. They also make value-added products, like orange rosemary scones, and run workshops for children and home gardeners. The farm employs nearly 50 people each summer, 20 in the winter.

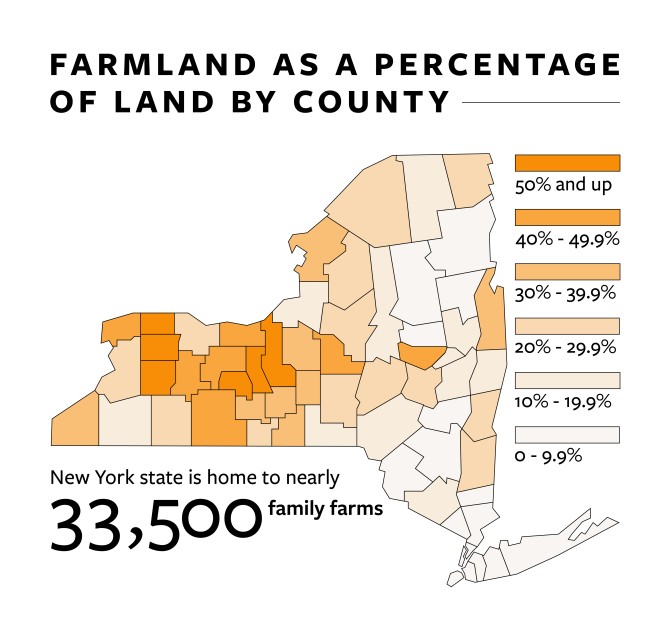

Source: N.Y. Depart. of Agriculture and Markets 2021 Annual Report, p. 3

20% of New York, or nearly 7 million acres, is farmland.

In 2019, 15 years after they nearly auctioned off their equipment, the Lees were named Farmers of the Year by the Northeast Organic Farming Association.

“FarmNet to me has almost been like a fairy godmother sitting over my shoulder,” says Lee, who has turned to FarmNet several times in his career. “I wish I didn’t have to call on them for the time periods that I did. It was at very tough junctures in my life. … I was grateful that FarmNet was there to rely on and to look to for help.”

Lee is one of the thousands of farmers across New York state who have relied on FarmNet for help with everything from financial analysis to anxiety and depression.

It’s important to support farmers because they play a crucial role in the state culture and economy, says Greg Mruk, FarmNet’s executive director and a former FarmNet financial consultant. “New York is an incredibly rural state, which surprises a lot of people. And a lot of that rural culture centers around the farm, and the family farm,” he says.

Source: N.Y. Depart. of Agriculture and Markets 2021 Annual Report, p. 3

U.S. Department of Agriculture, p. 6, Figure 8

New York state is home to nearly 33,500 family farms.

Those farms make important economic contributions. In 2021, New York agriculture produced roughly $3.3 billion in gross domestic product and paid close to $1 billion in wages, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

But the job comes with stress, from financial pressures outside their control like the high land values the Lees experienced, to the emotional complications of a multigenerational business.

For some, the stress can become untenable. Male farmers, ranchers and other agricultural managers in the U.S. have a significantly higher rate of suicide deaths – 43.2 per 100,000 – compared to the average across all other occupations of 27.4 per 100,000, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

FarmNet has helped the Lees navigate both emotional and financial obstacles, says Fred’s son Will Lee, 37, who helps run the farm as a part owner. “Having FarmNet as an adviser has given my father the capability to feel secure and sound in the decisions that he’s making,” Will Lee says. “FarmNet was there for him when he needed it the most.”

Sang Lee Farms grows nearly 100 varieties of vegetables, fruits and herbs on more than 100 acres.

A holistic approach

Lee’s uncle started the farm around 1946, after he refused to work in the laundry business his father had started after emigrating from China in 1921. Lee’s father, George Lee, and another uncle joined the farm after serving in the U.S. armed forces during World War II. The three grew Asian vegetables at a few different Long Island locations, selling the harvest in New York City and to Chinese restaurants on Long Island.

When Fred Lee was a child, his aunt would pay him 25 cents per week to clean and set the work crew’s lunch table at midday. “The indoctrination started very early in my life,” Lee quips.

He steps into greenhouse No. 5, where neat rows of baby lettuces glow in the sunlight like emeralds and rubies dotting the rich soil. There’s red oak, red romaine, green romaine, green leaf, red Boston, as well as Italian parsley and arugula. As Lee walks through the greenhouse, he assesses the crop. “Is there adequate moisture? Does the manager need to know that he’s got to turn on the water a little bit longer? Where are the weeds sitting? Are there aphids underneath the leaves?” Lee says. “I hit all the hot spots and if it generally looks good, I’ll walk out.”

At his office, he sits down at his desk among neat stacks of paperwork. There are certificates of insurance to secure for the farmers markets where they will sell their produce this summer. A registration form needs to be filled out for a new secondhand farm truck. A broken irrigation pipe serves as a paperweight.

Lee learned early on that the financial part of the business is as important as cultivation. “It is always a balancing act,” he says. “Do we have enough funds to get through the next month before our crop harvest?”

Rising interest rates are the main financial concern facing New York farmers, says Wayne Knoblauch, faculty director of FarmNet and professor in the Charles H. Dyson School of Applied Economics and Management, part of the Cornell SC Johnson College of Business and the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences (CALS). “That’s one of the current issues, helping individuals who are either applying for new loans or having adjustable-rate mortgages, getting lines of credit to buy feed, seed, fertilizer,” says Knoblauch, who is a farmer.

High interest rates were one of the factors that prompted Cornell to found FarmNet in 1986. During the 1980s farm crisis, milk prices dropped precipitously due to low grain prices, leaving New York dairy farmers struggling to pay their mortgages and creditors. “Interest rates were rising, energy costs were rising, commodity prices were falling. And the underlying asset values were also falling,” Knoblauch says. “That combination of factors put a tremendous financial strain on the rural economy.”

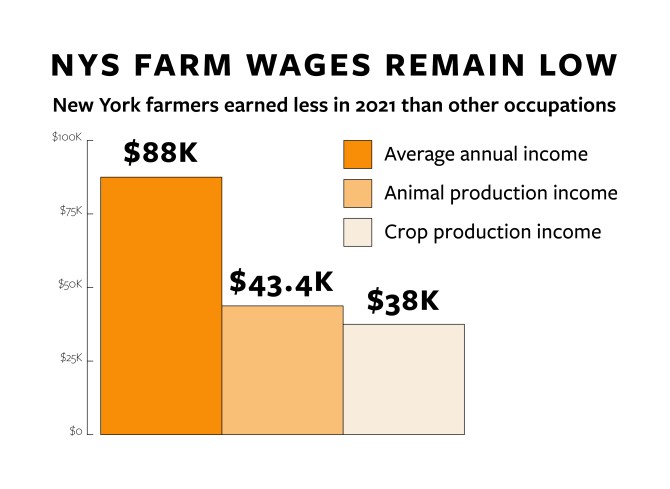

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, p. 3, Figure 3

New York farmers earned less on average than workers in other occupations in 2021.

CALS and Cornell Cooperative Extension charged a faculty committee with determining Cornell’s response. “Our thought was that we needed a program beyond what the normal Cornell and cooperative extension programs could offer,” he says.

CALS authorized funds to start the program, which is now housed and operated at Dyson and is funded primarily by Cornell and the New York State Department of Agriculture & Markets and Office of Mental Health.

Faculty members continue to play a key role in FarmNet. They educate FarmNet’s 50 consultants, who are often farmers themselves and have deep ties to the ag community, three times per year on current ag-related topics. “That has been critical,” Knoblauch says.

In March, consultants gathered for two days of training on issues from how to work with U.S. Department of Agriculture loan officers to what makes a farm viable and how to support clients who are distressed. Steve Kyle, associate professor at Dyson, gave a nationwide economic outlook.

“Farmers are absolutely vital to New York state, and, daily, they face challenges, from shifting commodities markets to personal tragedies,” says Katherine McComas, vice provost for engagement and land-grant affairs. “For more than three decades, New York FarmNet has sought to help farm families manage these stressors and, I think, serves as a testament to Cornell’s enduring commitment to work hand-in-hand with our community partners to improve the lives and livelihoods of New Yorkers.”

Becky Wiseman, a New York FarmNet family consultant, is a licensed clinical social worker who has worked with farmers on Long Island for 30 years.

“I really needed help”

Farmers will often call FarmNet with a financial problem, but a personal or family issue will quickly emerge as the real issue, says Becky Wiseman, a FarmNet family consultant.

“So I ask a couple of questions. ‘How are things between you? Is there anything that has happened in the past?’” says Wiseman, a licensed clinical social worker who has worked with farmers on Long Island for 30 years. “Then sometimes things tumble out. ‘Well, my daughter is really sick.’ Or ‘We just lost Grandpa.’ Or ‘Uncle Roy, he died from suicide.’

“And so you take a break from talking about the issues related to business planning because you can’t talk about business planning if people are mourning a loss.”

It was a devastating loss that prompted Fred Lee to call FarmNet again, in 2019. “I don’t know how they understood me because I was crying most of the time on the phone,” Lee says.

His wife had served him with divorce papers after 38 years of marriage, saying she wanted more work-life balance. “Initially, it was such a hard event for me that I was shattered,” Lee says. “I didn’t know what to do, so I was barely functional. There were times that I didn’t think I could make it to the next day.”

Wiseman went to Lee’s farm that day. At any farm visit, her first step is to listen without judgment, she says. “I am stepping into their world. And I learned that I need to be quiet and listen, because I have to learn their worldview,” she says.

For Lee, talking about his feelings was the greatest challenge. “It was hard to share fears and doubts and insecurities,” he says. “But it helped me move forward.”

They continued to meet on a regular basis, usually off the farm so he could share his feelings freely. With Wisemen’s encouragement, he began to see a therapist, and continues to do so. “There was a time period where I was terribly, terribly, horribly embarrassed to admit that or to share that with anyone, but it helped me,” he says. “And so if it helps someone else, that’s good.”

Over time, he gained the emotional equilibrium to work through the business implications of the divorce, with assistance from Mruk, who was Lee’s financial consultant.

“I’m grateful to FarmNet for being there when I really needed help,” Lee says.

Asian pear and apple trees and fig bushes bloom at Sang Lee Farms’ orchard.

The next generation

Lucy Senesac, who runs the farm’s day-to-day retail and CSA operations with her life-partner, Will Lee, reaches into a shin-high forest of green fronds at the entrance of greenhouse No. 10. She pulls out a Javelin parsnip, shaking off the soil to show Fred and Will the carrot-sized root. They discuss whether the parsnips will be big enough to include in the upcoming CSA share, and the timing of the next delivery of boron, a soil amendment.

Following a FarmNet strategic plan, Lee has transferred some ownership of the farm to Senesac and his son Will.

“Having multiple generations involved is a good way to have checks and balances on the farm, because you automatically have different perspectives that are valuable and new energy and sage advice and wisdom,” Senesac says.

Generational transfers and succession planning are two of the most common situations FarmNet consultants help with, Mruk says. “It is, first off, asking the older generation, are they ready to let go? Because most farmers tell you, they slow down, but they don’t retire.”

Fred Lee will likely continue to work “until he is 150,” Will Lee says. “Lucy and I are here to support that decision, however he decides to make it. … We want him around, and we appreciate his guidance.”

Not all generational transitions go so smoothly. Some adult children struggle with wanting to do things their own way while anticipating what their parents will say about their decisions. Those conversations can be uncomfortable. But the effect can be transformational for a farm family, Wiseman says.

“There’s no perfect family,” she says. “But if you can have a healthy family, healthy discussions, healthy disagreements, then that will help farmers continue farming.”

Source: New York FarmNet

85% of farms surveyed stayed in business after a New York FarmNet consultation.

That’s what Fred Lee wants for Sang Lee Farms.

“It feels good to think that we’re able to continue the efforts that my dad and my uncles made,” Lee says. “And I’m hoping … that Will and Lucy could have a good life, farming and continuing the business. That’s my hope and wish.”

The story and video were developed and produced by Susan Kelley and Noël Heaney, with support from Ryan Young and Matt Fondeur, and edited by Melanie Lefkowitz and Lindsay France. The graphics were developed and edited by Caitlin Cook, Eduardo Merchán and Marijke van Niekerk.

Media Contact

Abby Kozlowski

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe