Panelists Pedro X. Molina, Elja Sharifi, and Khadija Monis '24 (from left to right) spoke about their artistic practices and the threats they've faced for pursuing their art.

For threatened artists, free expression is political and personal

By

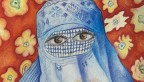

Sharifa “Elja” Sharifi created paintings and drawings of women, exploring the female form and celebrating female desire. Khadija Monis ’24 wrote poems that sprung from her deepest emotions, sometimes weeping as she wrote. Pedro X. Molina used his artistic skills to comment on politics and current affairs.

Their motivations differ, but for each, practicing their art in their home countries meant risking imprisonment or worse. All have been able to pursue their creative work at Cornell as supported scholars under threat.

Sharifi and Monis (from Afghanistan) and Molina (Nicaragua) discussed their art and lives in “Politics, Art, and Free Expression,” a panel at the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art on Sept. 22. The event, moderated by Mario Einaudi Center for International Studies director Rachel Beatty Riedl, kicks off Global Cornell’s contribution to this year’s campuswide theme, “The Indispensable Condition: Freedom of Expression at Cornell.”

In her opening remarks, Riedl – Einaudi's John S. Knight Professor of International Studies and government professor in the College of Arts and Sciences and the Cornell Jeb E. Brooks School of Public Policy – said freedom of artistic expression is essential to democracy, just as freedom of academic expression is essential to education.

“The capacity to dream and imagine different possibilities of justice, of freedom, of thriving: these require the ability to think and speak freely, to exchange, and to learn, to push boundaries and to be changed by those inputs and experiences,” she said.

Molina came to Ithaca in 2018 as a guest of Ithaca City of Asylum and became an Artist Protection Fund Fellow and visiting critic at the Einaudi Center’s Latin American and Caribbean Studies Program in 2021. During the event, he showed drawings depicting his development as an artist – and ultimately as a leading critic of the government of strongman Daniel Ortega.

Living in Ithaca has not blunted his desire to effect change. Since he arrived, he has produced more than 1,640 cartoons, many skewering the Ortega regime. “I feel the responsibility to say what millions of Nicaraguans cannot say out of fear, or because they are political prisoners, or because they were forcibly exiled,” he said.

Monis is an interdisciplinary studies undergraduate in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. She spent 15 years as a refugee in Pakistan but returned to Afghanistan after high school and worked as a licensed midwife there. She fled in August 2021 after the Taliban retook power and was admitted to Cornell last year.

She read two poems in Dari, asking audience members to close their eyes and listen to the music. One, written after a 2015 incident in which a woman was stoned to death for alleged anti-Islamic behavior, “shares how a woman gifts her power, her creativity, her talent, her open-mindedness, her wisdom and her soul in support of men to achieve their goals for a hopeful future, even when hers are being trampled upon.”

The other poem imagines a woman returning home after 15 years in exile and her “disappointment with seeing that her society lost the spirit and freedom they had before.” The poem was written the day before Monis left Afghanistan.

Sharifi, a 2022-23 Artist Protection Fund Fellow at the Johnson Museum, said her paintings of nudes and independent-minded women were not designed to provoke, but to probe questions that have always fascinated her. “Why should a woman be embarrassed by her body?” she asked. “It didn’t matter if it was important to people. It was important to me.”

Sharifi said “Afghanistan has become a cemetery of art,” but noted that censorship is not new there. Even before the Taliban took control, she had to hide hundreds of her artworks at her parents’ house.

In a discussion, the artists touched on issues ranging from the limits of an artists’ social responsibility to the power of humor against autocrats. Among their points of agreement: if they and their art have been threatened, it’s because authoritarian leaders feel threatened by them.

“It’s all about connection,” Molina said. “For me, that’s the secret of art.”

Jonathan Miller is a freelance writer for Global Cornell.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe