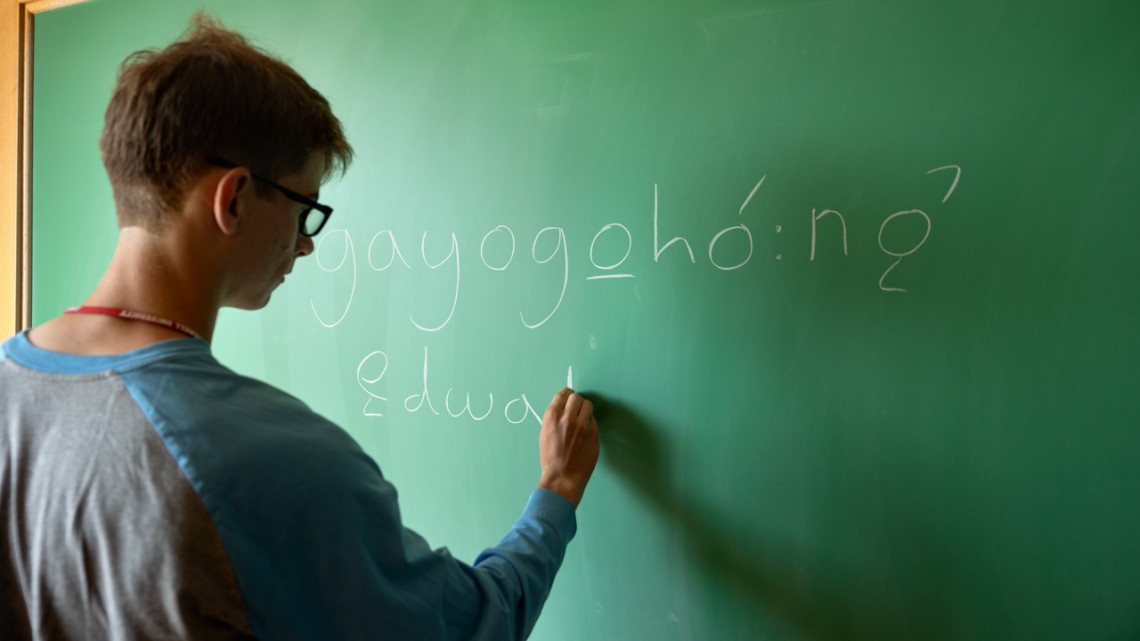

Oliver Peck Lambert ’27 has been studying the Gayogohó:nǫˀ language since high school.

Coming home: Gayogohó:nǫˀ language programs expand reach

By Kathy Hovis

This summer, Jim Wikel, a member of the Gayogohó:nǫˀ diaspora who now lives in Oregon, traveled to his ancestral homeland in New York for the first time, to learn his ancestral language with 40 other diaspora members at a Cornell camp.

Just being in the region was profound, Wikel said.

“One night as we were singing, I realized that this was the first time that land had heard those songs in 247 years,” he said.

The weeklong camp in August was part of four Cornell-funded projects expanding efforts to preserve and highlight Gayogohó:nǫˀ (Cayuga Nation) language and culture, in western New York and throughout the country. Other projects include a NASA-funded effort to teach how the Gayogohó:nǫˀ people use stars to plan and navigate, and Gayogohó:nǫˀ language classes at Cornell and beyond.

The Finger Lakes region was the traditional homeland of the Gayogohó:nǫˀ, who are now spread throughout the U.S. and Canada. Many members have relocated to the Six Nations of the Grand River reserve in Canada, Seneca territory in western New York and to the Seneca-Cayuga Nation reservation and elsewhere in Oklahoma.

“It’s only over Zoom that we’ve been able to do our language classes, so it was great to be able to do them in person [at the camp],” said Stephen Henhawk, the youngest Gayogohó:nǫˀ first language speaker and historian, and a research associate with Cornell’s Department of Linguistics and American Indian and Indigenous Studies Program, who helped lead the camp. “But the biggest part of this was allowing people to come home, to connect with the land.”

Wikel said the camp, held at Cornell’s Arnot Teaching and Research Forest in Van Etten, New York, offered “a week of experiences that were too deep and powerful for words.”

Both Wikel’s mother and grandfather were sent to boarding schools, where they lost their language and culture.

“As a result, I was not raised around the culture,” he said. “We would go visit my grandparents, but my grandpa never spoke about what happened in the residential school. I’m the first one in my family to have an Indian name since my grandfather.”

Wikel, who has been studying the language since 2015, said his goal is to be able to recite the long version of the Gayogohó:nǫˀ Thanksgiving prayer. Right now, he’s proud of the fact that he’s able to take part in the yearly ceremonies where babies are given their Gayogohó:nǫˀ names.

The campers took part in intensive language classes, traveled throughout the region to important spots in Gayogohó:nǫˀ history, got their hands dirty at the native farming plots, ate ancestral foods and explored the stars and nature of their ancestral homelands. They visited culturally significant waterfalls, valleys and meadows; some appear in traditional songs. For example, Taughannock Falls State Park is named after the Gayogohó:nǫˀ word for “waterfall.”

A Cornell Atkinson Center for Sustainablility grant supported the summer language camp at the Arnot Forest camp.

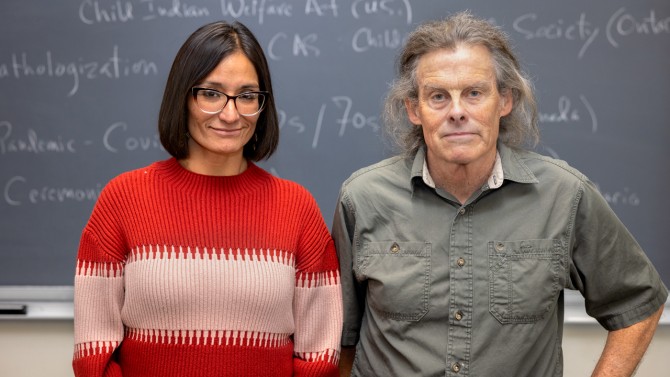

Henhawk and John Whitman, professor of linguistics in the College of Arts and Sciences (A&S), hope to run this camp next summer, as well.

“What seems most important now is to reach out to Gayogohó:nǫˀ people involved in reclaiming this critically endangered language,” Whitman said. Students came from Oklahoma, Missouri, Kansas, Washington state, Alaska, Hawaii and Canada for the camp, he said. “All of them were coming to their homeland for the first time.”

Michelle Seneca, a co-leader of the Gayogohó:nǫˀ Learning Project (GLP), a partnership of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people working to promote the language and culture, was also instrumental in making the camp happen.

“We also had a night where we had a non-Indigenous and Indigenous dinner together with members of the GLP,” said Seneca, who grew up on the Seneca Cattaraugus reservation in western New York. “To me, working with this group is like us polishing the Silver Covenant Chain [an agreement of peace and friendship between Indigenous people and Europeans].”

Telling stories through stars

New York high schoolers studying the nighttime skies in their astronomy classes could soon also be learning how the Gayogohó:nǫˀ people use stars to plan ceremonies, determine planting times or just find their way home.

Through the project, funded by a NASA New York Space Grant, Cornell faculty are working with local Indigenous people to transfer Gayogohó:nǫˀ oral history about astronomy into a curriculum option for the Six Nations reservation in Canada and for New York State public schools.

“A lot of the teaching we have to do with stars tells us when to have ceremonies or helps with planting practices or direction, telling us to come home,” Henhawk said. “A lot of this teaching is on the verge of being lost because the stories were only told in Gayogohó:nǫˀ.”

A challenge for teaching Gayogohó:nǫˀ related to astronomy has always been location. Most of the members of the nation don’t live in New York anymore.

“A lot of times when we’re doing teaching about the traditions with an Oklahoma group, it’s tough because they’re looking at a different sky,” Henhawk said. “So, the stories about the stars helping us with directions are off for them.”

The public school curriculum won’t be able to go in-depth about Gayogohó:nǫˀ language and culture, but “my hope is that it will spark some interest in these kids in Gayogohó:nǫˀ and they will want to learn more,” Henhawk said.

Along with the NASA project, grants have funded:

- Twice-weekly Zoom language classes taught by Henhawk, which reach students spread as far as Canada, Alaska, Oklahoma and Washington state, funded by an Engaged Cornell grant from the David M. Einhorn Center for Community Engagement and a Migrations Initiative grant;

- Projects underway with the Cornell Botanic Gardens and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology to add Gayogohó:nǫˀnames to their public-facing information about plants and birds; and

- A new course taught by Whitman, Introduction to Language Endangerment and Revitalization, with a focus on Gayogohó:nǫˀ language.

The new initiatives – spearheaded on campus by AIISP and faculty in A&S and the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences – build on efforts that brought about the creation of the GLP. It also helped spark community language classes for two years at the History Center of Tompkins County that reached 75 people, following the initation of a Gayogohó:nǫˀ language class, Linguistics/AIISP 3342 Cayuga Language and Culture, in A&S in 2019.

Language learning comes first

Maintaining and spreading knowledge of the language is one of the highest priorities of the initiative. There are fewer than 10 living first-language speakers of Gayogohó:nǫˀ and Henhawk is the youngest.

Cornell student interest in classes in Gayogohó:nǫˀ language and culture still runs high on campus, with both an introductory and an intermediate class now offered.

Henhawk, Whitman and others have been working on curriculum and teaching materials so that Gayogohó:nǫˀcan more easily be taught by people who aren’t first-language speakers.

“The level of teaching in Mohawk has been very successful in producing second-language speakers, so we would like to take those materials and convert them for Gayogohó:nǫˀ, but also make sure those materials are authentic,” Whitman said.

Oliver Lambert ’27, now a first-year student in A&S, is helping with these efforts. He audited Cornell Gayogohó:nǫˀ language classes taught by Henhawk starting in 2019 when he was a high school student growing up in Ithaca.

This year, Lambert is working on a research project with Whitman to study the patterns of stress and accent in Gayogohó:nǫˀ. “Getting the intonation of the word and the rhythm of how it’s spoken is what I’m focusing on,” he said. Helping to find patterns in rhythm, loudness and pitch can help teach the language to new learners.

Lambert, who has interests in linguistics, computer science and chemistry, said he plans to continue his work with Gayogohó:nǫˀ throughout college.

“What we hope to become here is a center of activity on Gayogohó:nǫˀ teaching and learning,” Whitman said. “But there’s a lot to do.”

Kathy Hovis is a writer for the College of Arts and Sciences.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe