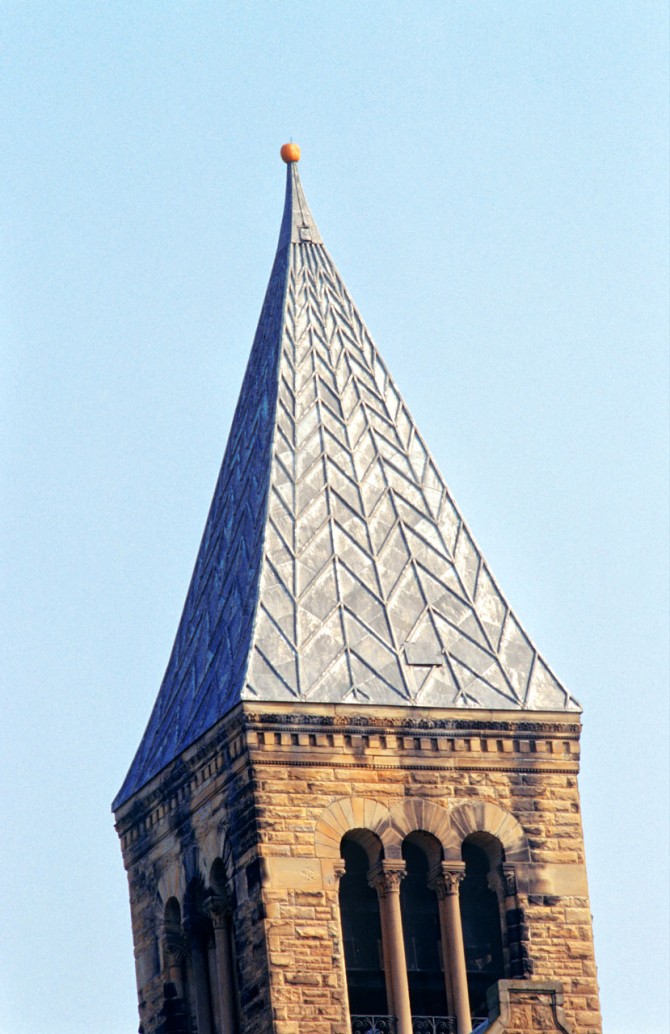

J. Shermeta, associate university architect in Facilities and Campus Services, explains how changes to McGraw Tower’s roof design will maintain its iconic look while protecting it for years to come.

McGraw Tower restoration preserves the past, ensures the future

By Holly Hartigan, Cornell Chronicle

In 1891, the University Library, with its 173-foot clock tower, was the newest building on the Arts Quad.

Cows grazed on Libe Slope as 1,538 enrolled students glanced up to the clocks to check the time.

The building glowed with light produced by the newfangled electric lightbulb, and daily concerts rang out from its nine bells.

More than 130 years later, enrollment has expanded to more than 25,000 students, the number of bells has grown to 21 and time and weather have taken a toll on McGraw Tower. A $7 million restoration of the tower and adjacent Uris Library, underway since summer 2023 and expected to be completed in November, includes replacing roofs, repairing masonry and shoring up a century-old entryway.

“This is probably the most iconic building in the region,” said Jon Ladley, director of facilities planning for Cornell University Library, who is part of the planning and project management team. “Taking care of this now is definitely the right thing to do from a stewardship point of view, but also from a preservation point of view.”

In July 2023, construction crews began carefully erecting scaffolding and a construction elevator around the tower in preparation to replace the famous pyramidal roof.

Work has halted for the winter, but in the spring crews will begin removing the roof’s lead-coated copper sheets. The roof was last replaced in the 1930s and has been repaired and patched many times since then, but water keeps finding a way in.

The new roof will maintain the look of the current lead-gray chevron pattern but will be made from sheet lead, a more durable and malleable material. Commonly used on historic buildings today, the sheet lead does not pose any threat to the humans and plants below. Design tweaks to the batten pattern on the roof should prevent water from collecting and lessen the risk of leaks.

“It’s going to look pretty similar,” Ladley said. “It’s not going to have some of the color differences that you see in the lead-coated copper. It’s going to be one uniform color, and it should age uniformly too. It’s going to look a little different but pretty darn close to what folks are used to.”

While the scaffolding is up, crews will repaint the clock faces and steel hands.

“This whole project is historic restoration/maintenance,” Ladley said. “It’s all on the building exterior, and it’s all stuff that folks hopefully won’t notice and just be able to enjoy the building longer.”

The library’s open hours will remain the same during construction; the chimes will be silent during the day but will play on evenings and weekends, when crews are not on the roof. The tower will be closed for in-person concert viewing until construction is finished.

In addition to the work on the tower, so far crews have repaired the original sandstone stairs at the main Uris Library entrance, made safety improvements in the belfry, reconstructed the bell tower’s internal roof and replaced small mansard roofs around the building.

The spirit of the student body

Known as the University Library when it first opened on Oct. 7, 1891, the building and tower became a symbol of Cornell, a distinctive landmark that could be seen from miles around.

J. Shermeta, associate university architect in Facilities and Campus Services, said the building was regarded as “high-quality architecture” from its opening: beautiful and solemn, and practical in its utility and choice of materials.

Its mission differed from contemporary university libraries, which were little more than book warehouses with limited hours open only to faculty. In contrast, Cornell’s University Library was open to students and faculty alike. The cross-shape design, natural lighting and large reading room brought to life the vision of Cornell co-founder and first president A. D. White for the library to be a “secular cathedral” for books and learning.

In 1962 both buildings were renamed: Uris Library for Harold D. Uris ’25, who was a Cornell trustee from 1967 to 1972, and McGraw Tower after early university benefactors Jennie McGraw or her father, John McGraw. It’s unclear which McGraw the trustees at the time intended to honor – perhaps both.

In 1868, Jennie donated nine chimes to the university for its opening ceremony. Initially installed in McGraw Hall (named for her father), they were the first chimes to be housed and rung on an American college campus. But McGraw Hall couldn’t handle their weight, and 23 years later, the library tower was built to house them.

“We use the clock tower in times of celebration; we use the clock tower in times of mourning,” said Evan Earle ’02, M.S. ’14, the Dr. Peter J. Thaler University Archivist. “It’s the clock tower that we turn to to be the spirit of the student body and faculty and the rest of campus.”

From its early days, the tower has been a victim of pranksters, most famously when a pumpkin appeared atop the tower in 1997.

An earlier legend suggests a group of fraternity brothers climbed the tower one night in the 1920s and stole a set of clock hands. Dangling from a rope, one man supposedly unscrewed the clock hands before his fellow scofflaws hauled him back up to safety. In fear of being caught, the legend goes, they moved the hands to a nearby chapter of their fraternity at Hobart College in Geneva, New York, and later dropped them into Cayuga Lake. They retrieved them two years later and moved them to their fraternity basement until they turned up in a 1942 scrap metal drive.

Earle isn’t sure how apocryphal that story is, but it adds to the legend and character of the tower. “It’s been repeated a number of times but in different ways; it makes you feel there is a kernel of truth,” he said.

Shermeta has a long list of items that have mysteriously appeared at the top of the tower, including a disco ball. A new pumpkin made its way up there around Halloween 2023. The roofing crew quickly removed it.

The new roof will no longer have a hatch through which decades of daredevils may have climbed to access the spire, he said.

Students traverse the original 1891 steps to Uris Library on March 1. As part of this restoration project, crews removed the steps, shored up the base, and then replaced the steps, preserving the sandstone steps that more than a century of Cornellians have trod.

The next 100 years

The City of Ithaca Landmarks Preservation Commission (ILPC) created the Cornell Arts Quadrangle Historic District in 1990. ILPC review and approval are required before substantial changes can be made to the exteriors of buildings in the historic district to ensure the results remain true to the “period of historic significance” from 1868 to 1919 when Cornell erected most of the buildings on the Arts Quad.

Originally topped with a roof of Spanish tile, the tower got its lead-coated copper roof in 1932, outside of the period of historic significance. “However, the ILPC accepted a replacement in kind of the 1932 roof with a similar sheet-lead roof due to the iconic character of the roof, which has gained significance in its own right and is considered a character-defining feature of the building and the district,” Shermeta said.

The ILPC granted the project a certificate of appropriateness before any construction work began.

“We’re really sensitive to any sort of work that goes on with historic buildings,” Earle said. “The folks who manage those projects really consider the historic impact and then do their research to figure out what can we do to preserve this as best as possible, while still being practical for the university.”

The university worked with specialists in architectural preservation to find restoration strategies that would be true to the iconic look and feel of the building but would enable the building to stand another 100 years.

At the Uris Library main entrance, the restoration team went to great lengths to preserve a tangible connection to the past. The Medina sandstone steps, which students have trod for more than a century, were sagging, and water was infiltrating the building around them. In fall 2023, crews pulled out the stairs, shored up their base, added water barriers and then reset the original stairs.

“It goes beyond the aesthetic of the building,” Earle said. “Knowing that you are touching something just as those before you have done gives you a far greater connection to them. A parallel experience can be how facsimiles of letters from famous individuals may provide all that is needed for research, but holding a letter that Ezra Cornell, for example, wrote and also held in his hand is a completely different experience than just reading the letter in a textbook.”

That’s why the University Archives will add a piece of the current tower roof to its collections. It’s not the typical type of item kept in the archives. “There’s not a tremendous amount of research value there,” Earle said. “But there is value in saving for the future an item that has this shared connection to all who had a moment in its presence.”

When work resumes on March 11, crews will resurrect the fence across Ho Plaza to Sage Chapel, closing off the walkway. Although the tower scaffolding may temporarily change the campus skyline, this project helps to ensure McGraw Tower and Uris Library remain a stalwart presence on campus – a place central to the visual and auditory identity of Cornell.

“Construction is part of campus life, and if we didn’t have construction, it would mean we weren’t progressing and we’re stagnant,” Earle said. “We should be appreciative that we have the means to continue to grow and update our facilities.”

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe