Photo Essay

Vertebrate 3D scan project opens collections to all

By Krishna Ramanujan, Cornell Chronicle

A venture to digitize vertebrate collections in museums and make them freely available online for anyone to access has reached a milestone. The project has created 3D CT scans of some 13,000 specimens, representing more than half the genera of birds, amphibians, reptiles, fishes and mammals.

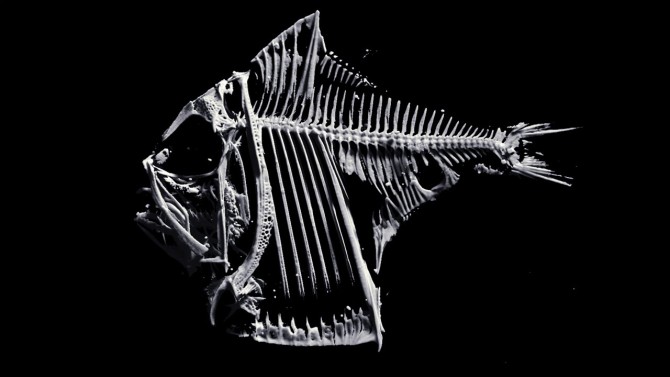

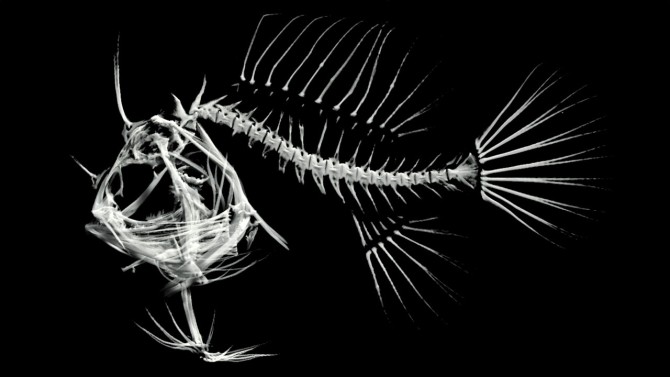

Lateral view of piranha (Serrasalmus iridopsis); collected in South America, by C. F. Hartt who died in 1878. The exact year of collection is not known, but was likely in the latter half of the 19th century.

The project, the oVert (openVertebrate) Thematic Collection Network, has just wrapped up a four-year, $2.5 million National Science Foundation grant, with the efforts to date described in a paper published March 6 in BioScience.

The Cornell Museum of Vertebrates, one of 18 institutions taking part in oVert, has uploaded roughly 500 CT scans of specimens from its collections. The museum holds approximately 1.3 million fish specimens, 27,000 reptiles and amphibians (collectively called herps), 57,000 birds and 23,000 mammal specimens.

“Not everyone is interested in making a trip to a museum, so by digitizing specimens, placing everything up on a website and making it free, anyone who wants to access it can without having to leave the house, which allows for much more equitable access,” said Casey Dillman, curator of fishes and herps at the Cornell Museum of Vertebrates in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, and a co-author of the Bioscience paper.

So far, users have included artists, high school and college students, educators and scientists.

oVert allows the natural history collections that are represented to be used in collaborative ways, such as in classrooms. The format has made it simpler to compare anatomies of different species.

“You can do so many things,” Dillman said. “You can compare specimens and look at the evolution of limbs, or wings in birds and bats, or gills in fishes.”

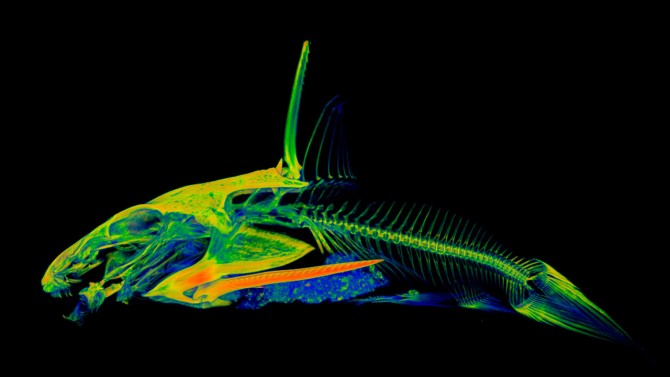

Views of a juvenile pied-billed grebe (Podilymbus podiceps) that perished swallowing a fish.

One limitation of the platform is that each specimen dataset can be 2 to 3 gigabytes in size, requiring users to have access to a computer with an expensive graphics processor to visualize the data. “Not everyone’s laptop can do that,” Dillman said.

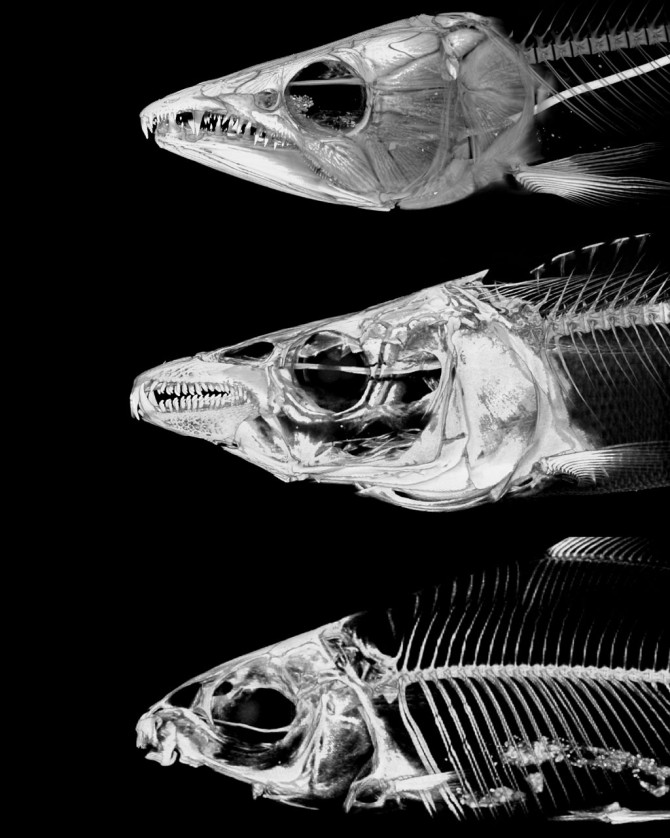

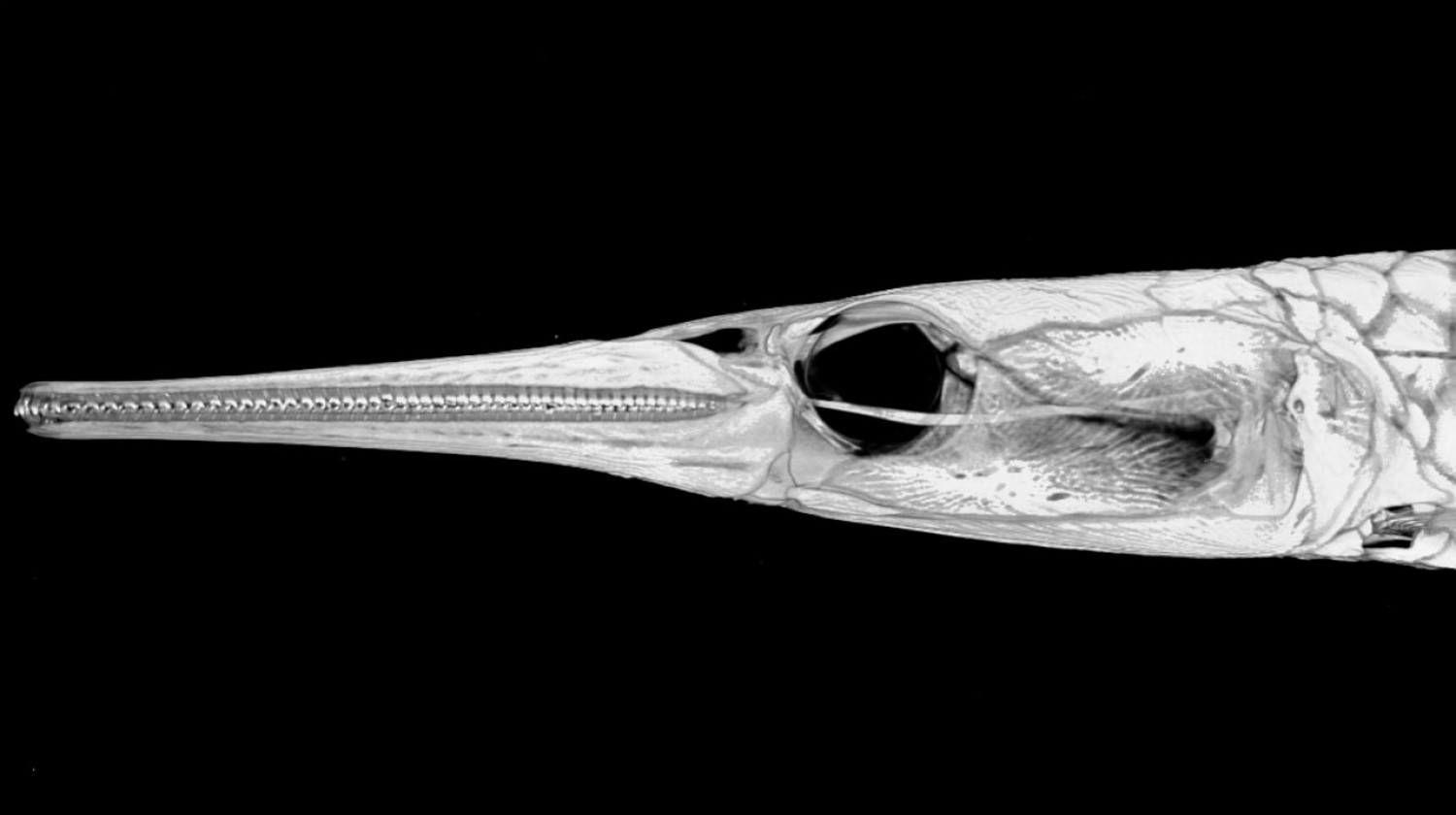

Dorsal view of a shovelnose sturgeon (Scaphirhynchus platorynchus); one of the three species of shovelnose sturgeon in the U.S. The other two species are federally endangered. This specimen was collected in 1909 in Emanuel Creek at Springfield, South Dakota.

“Not everyone is interested in making a trip to a museum, so by digitizing specimens, placing everything up on a website and making it free, anyone who wants to access it can without having to leave the house, which allows for much more equitable access.”

Casey Dillman, curator of fishes and herps at the Cornell Museum of Vertebrates in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences

The idea behind the grant was to CT scan one species of every genus of vertebrate, thereby building an online digital library of each organism’s appearance – its phenotype, or observable characteristics – with respect to the skeletal anatomy. While most of the images are skeletons, some were stained with a special solution to provide better contrast and visualize soft tissues, such as skin and muscles. The scanners use X-rays, which can be set as weak as a medical X-ray for soft tissue, or strong enough to view through rocks and fossils.

Museum catalog numbers included with each image link to the institutional database where the specimen originated. Database entries include when, where and by whom a specimen was collected.

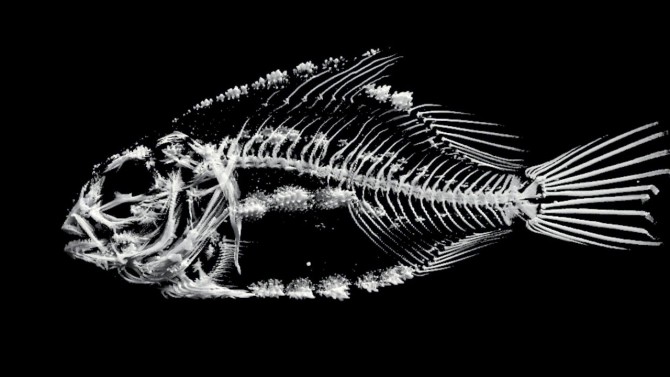

Lateral view of a sargassum fish (Histrio histrio); collected from the south shore of Boca Chica Bay in Monroe County, Florida, in 1979.

In many ways, the oVert project is just getting started, Dillman said. “Thirteen thousand species isn’t even scratching the surface of vertebrate diversity,” he said.

For example, there are more than 36,000 species of fishes alone; one species per genus is a good start, he said, but it will take time and additional funds to represent the great depth of diversity.

“If you think about some of the fish lineages in North America, there might be 200 species within a genus,” he said.

Each round of funding will allow the teams to continue to represent more genera, then add more species from each genus.

David Blackburn, curator of herpetology at the Florida Museum of Natural History in Gainesville, Florida, was principal investigator of the grant.

Lateral view of Belonophago hutsebouti; collected in the Lékénie River, Republic of the Congo, in 2002.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe