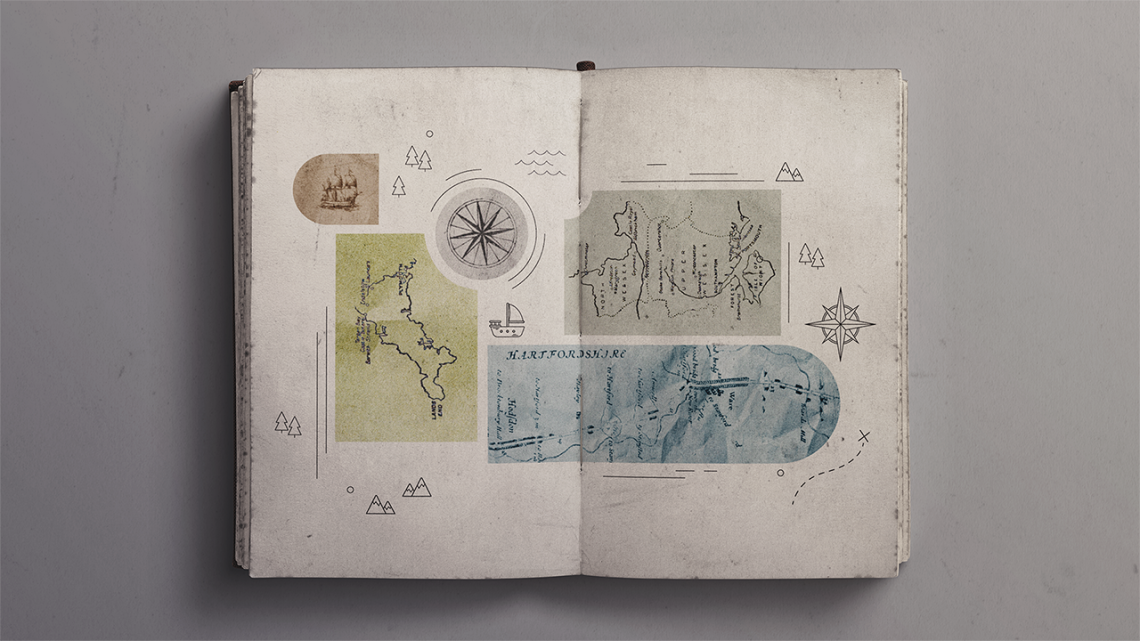

Digital humanities scholars chart lost art of maps in novels

By Louis DiPietro

Books with maps are like Captain Flint’s buried loot in Robert Louis Stevenson’s “Treasure Island” – a rare find, according to new Cornell research.

Digital humanities scholars from the Cornell Ann S. Bowers of Computing and Information Science have developed a computational system to mine maps from nearly 100,000 digitized books from the 19th and early 20th centuries, discovering that just 1.7% of novels include maps, mostly at the beginning or end, among other findings.

They also discovered that 25% of maps in novels depict fictional settings, and military and detective fiction – not fantasy or science fiction – were the book genres most likely to contain a map, contrary to initial hunches.

The research illustrates how Cornell scholars in the field of digital humanities use computational methods, including artificial intelligence, to unearth insights from literature about culture and society that would otherwise evade the most vigilant readers. This new method allows scholars to explore more deeply the spatial movements of literary characters across both real and imaginary lands. Previously, the study of character mobility was limited to real places.

“We’re interested in scale. It’s cool that we can figure out how far characters move in fiction epics like ‘Lord of the Rings,’ but that’s one novel. We want to be able to click a button and know how far characters move across 100,000 novels,” said Axel Bax, a doctoral student in the field of information science and lead author of “Castles, Battlefields, and Continents: A Dataset of Maps from Literature,” which he presented at the conference on Computational Humanities Research on Dec. 11 in Luxembourg. “We’ve identified these maps so we can do this for novels with real and fictional settings alike.”

The method builds on existing work by co-author Matthew Wilkens, associate professor of information science in Cornell Bowers, who mines libraries of online texts representing millions of pages to study gender and geography across British literature and calculate the distances real and fictional characters travel in the works.

Before computational methods, the team’s primary research questions – “How often do maps appear in literature?” and “How did that change over time?” – were too broad and too widely distributed for literary scholars to even consider, let alone answer definitively.

As part of their research, authors asked literary scholars anyway.

“The scholars we surveyed had no idea,” Wilkens said. “It’s not that often you get to discover something that almost everyone in your field cares about, but no one has any firm grasp on.”

For their system, the team used a batch of neural network models, a machine learning tool for image recognition and other areas, and trained them to identify maps from more than 32 million pages of fiction published between 1800 and 1928 and stored in the HathiTrust Digital Library.

Elsewhere, the team found that existing MARC records – the machine-readable format used to describe and catalog books and resources in library systems – didn’t note the appearance of maps in more than half of the novels that contained them. The team’s system could help identify and correct such omissions, researchers said.

Future work will explore and compare the movements of characters in novels with real and fictional settings.

“If a novel has a fictional setting, we have a large enough sample size to explore whether or not characters move in fundamentally different ways than in novels with a real setting,” Bax said.

David Mimno, chair and professor of information science in Cornell Bowers, also co-authored the paper. This research was supported in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Louis DiPietro is a writer for the Cornell Ann S. Bowers College of Computing and Information Science.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe